The other day I heard Kim Stanley Robinson talk about The Ministry for the Future, his inspiring science fiction novel about tackling climate change and other huge societal challenges. I really like the book, even though I think “ministries” are the wrong direction. I believe that the energy needed to pull civilization back from the brink does not lie in the center. That’s where the current knots and lack of traction exist. It’s at the edges where the solutions lie—decentralized and growing from the bottom-up, like all most creativity does.

Our challenge is that our economic systems are revving society and the planet into out-of-control spirals. The scale required to change that spiraling is unlike anything we’ve faced. It was never going to be easy, but humans have a tendency to defer big problems to a point of crisis, and that has narrowed our options. We now need collective resolve on a scale that dwarfs anything we’ve yet known—and ways of transforming that resolve into large-scale, workable solutions.

This isn’t an argument against rallying governments, corporations, and Non-Governmental Organizations to the call. We need to throw everything we have at these problems. But the scale of these challenges demands new sources of resolve and creativity, the kind I believe will be found in a revitalized form of human community. Let’s call it “Decentralized Autonomous Community.”

Two Modern Containers of Community

Community is the oldest form of human organization there is, winding back through empires, rural villages, and ancient nomadic tribes. In more modern times, community has come to reside in two types of containers, one political and the other commercial. Each has positive aspects, of course, but both have also greatly undermined what we have come to expect from community.

Place-Based Communities

Whether it’s a neighborhood, town, or city, politically defined communities are the primary way we come together in a physical location. Place-based communities are the oldest forms of community.

Governance over the political entities that hold our place-based communities has changed a lot in recent centuries, particularly with the rise of representative democracy. As society has modernized, fewer of us now live in political jurisdictions small enough to maintain meaningful, Dunbar-sized community connections. Political engagement tends to happen at the city, county, state, and federal level, which is beyond the neighborhood scale where place-based community happens. As a result, the community spirit that once animated our body politic has largely evaporated. Politics is now the stuff of professionals, who increasingly expect to be paid market rates for their ‘work.’ As the influence of money has taken hold, community has lost its sway over the governance of our physical places.

Perhaps there’s little wonder, then, why so many of us, particularly in younger generations, have lost interest in the politics of places. In its stead, a new type of community has stolen our attention.

Common Interest Communities

This new type of community is defined by common interests. Its medium is not physical space, but ideas. The early prototypes of this type of community distilled around writers, and expanded rapidly with the printing press. Radio and television made these networks more compelling, but it wasn’t until the interactive connections of the Internet that real-time engagement with this type of community became possible. Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube helped us find people around the world who shared our interests, as we tried new formats, scales, and degrees of intimacy.

Almost all of these common interest communities are housed in corporate containers, which are good at using revenues to drive innovation. But their profit incentives often push these communities in horribly anti-social directions, like disinformation, culture war, and privacy abuse. Their enormous profitability concentrates wealth and their semi-feudal ownership and governance strips their stakeholders of the right to self determination.

When we allow our relationships with one another to be controlled by entities whose interests aren’t fully aligned with our own, we are asking for trouble. I’m not talking about close friends and family; these deeper connections don’t disappear when someone changes an email address or phone number. The problem is with lightweight connections, especially those formed around common interests. Without governance over these communities, it’s very easy for these relationships to be used in ways that harm us. Facebook’s abuses are well-documented, but far from isolated. Google+ users invested countless hours building relationships on the social network, only to have them disappear without any recourse when Google decided to kill the service. It was a shocking abuse of corporate power that led to hundreds of thousands of people losing connections with one another.

The Power of Community

While community has lost some of its vitality to these modern containers, we cannot afford to give up on it.

The first reason is personal. Community is part of the fabric of human relationships. It’s one of the most precious things we have, even if it’s gotten a little worn around the edges lately. I’m not talking about family and close friends, but the vitally important next ring of relationships, such as friends, associates, extended family, neighbors, and colleagues. Community is what holds our connections with the vast majority of the people in our lives. These connections can be perfunctory, cold, and uncaring, or they can anchor us in meaning and a deep sense of belonging. This isn’t some theoretical problem. Restoring our houses for community will make our lives tangibly better.

The second reason to care about revitalizing community is that it’s the only form of human organization strong enough to overcome resistance to tackling civilization’s great challenges. People power is the source, the headwaters, of all political and economic power. Though its potential is highly fragmented today, it is still capable of moving mountains. We saw its power coursing through the Civil Rights Movement, the Velvet Revolution, and to lesser degrees every time neighbors come together to revitalize a park or rally around a cherished local restaurant in a pandemic.

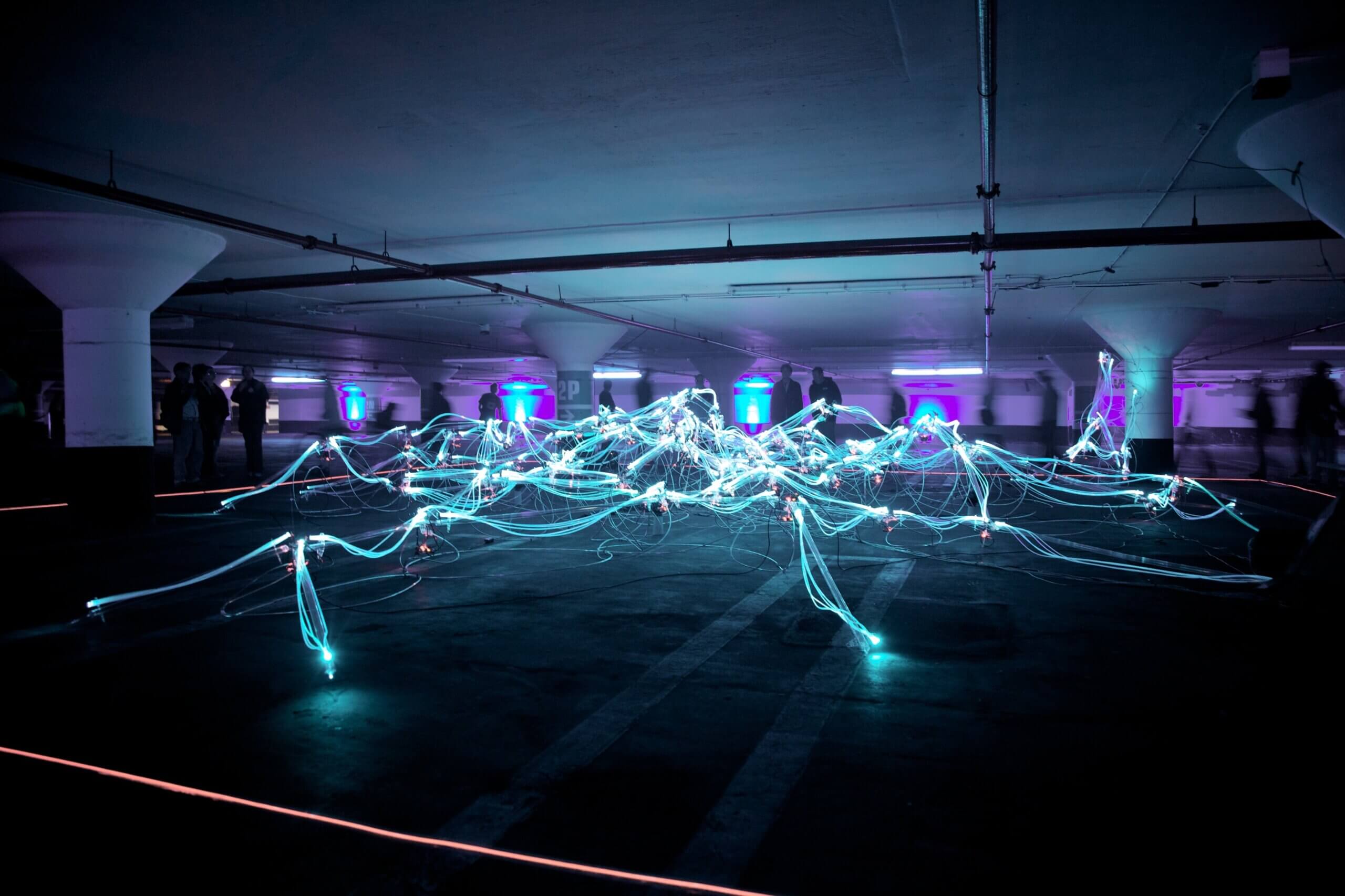

When people learn to organize themselves, they tap into the greatness that comes from being a part of something bigger than just themselves. Community is a field of quantum potential from which forms of great human coordination emerge.

Decentralized Autonomous Community

So, how do we infuse place-based and common interest communities with the vitality and power to save the world? This article is the first in a series exploring the role blockchains could play in answering this question.

For many, the very idea of blockchain-based communities may sound odd or just plain wrong. After all, isn’t Bitcoin consuming as much electricity as the Netherlands, facilitating illegal transactions, and being used to speculate on things that just don’t make any sense? Yes, these technologies, like all tools that have ever existed, cancreate serious problems in the world. But these same tools are also accelerating a movement for “regenerative economics” by building new kinds of blockchain-based, public goods.

I now spend much of my time swimming in this world of regenerative blockchain economics, learning about the burgeoning field of “token engineering” and the changes it makes possible in organizational design. I am also gaining hands-on experience in what it’s like to be part of a working community that’s built on this new technology.

Decentralized, autonomous communities have the ability to raise funding from their own members by issuing crypto-economic tokens. This new economics is helping to wean communities from the grips of venture capital and shareholder-centric forms of human organization. The resulting financial autonomy fuels innovation that is driving an explosion of creativity in bringing people together around common interests. These communities are also pioneering powerful new forms of self-governance, unlike anything in corporate-controlled communities—or even in place-based, politically governed ones.

These new forms of human organization could become how we build the resolve for tackling civilization’s great challenges. This is not a bet that blockchains will solve our problems, but that a new generation of communities using blockchains will be able to do so.