Key Takeaways:

- The scientists recognised the agglutinates as one of the potential reasons for lack of growth by the seedlings in the Apollo soil compared to the terrestrial soil, and also for the difference in growth patterns between the three lunar samples.

- This is the way that the regolith changes, through bombardment of the Moon’s surface by cosmic radiation, solar wind and minuscule meteorites, also known as space weathering.

- This is an important conclusion, because it demonstrates that plants could be grown in lunar habitats using the regolith as a resource.

What do you need to make your garden grow? As well as plenty of sunshine alternating with gentle showers of rain – and busy bees and butterflies to pollinate the plants – you need good, rich soil to provide essential minerals. But imagine you had no rich soil, or showers of rain, or bees and butterflies. And the sunshine was either too harsh and direct or absent – causing freezing temperatures.

Could plants grow in such an environment – and, if so, which ones? This is the question that colonists on the Moon (and Mars) would have to tackle if (or when) human exploration of our planetary neighbours goes ahead. Now a new study, published in Communications Biology, has started to provide answers.

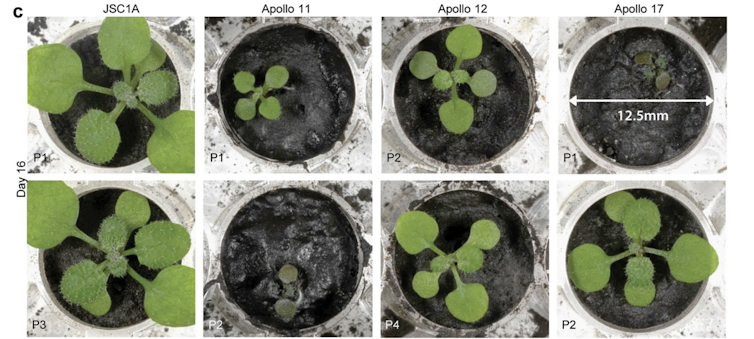

The researchers behind the study cultivated the fast-growing plant Arabidopsis thaliana in samples of lunar regolith (soil) brought back from three different places on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts.

Dry and barren soil

This is not the first time that attempts have been made to grow plants in lunar regolith though, but it is the first to demonstrate why they don’t thrive.

The lunar regolith is very different from terrestrial soils. For a start, it doesn’t contain organic matter (worms, bacteria, decaying plant matter) that is characteristic of soil on Earth. Neither does it have an inherent water content.

But it is composed of the same minerals as terrestrial soils, so assuming that the lack of water, sunlight and air is ameliorated by cultivating plants inside a lunar habitat, then the regolith could have the potential to grow plants.

The research showed that this is indeed the case. Seeds of A. thaliana germinated at the same rate in Apollo material as they did in the terrestrial soil. But while the plants in the terrestrial soil went on to develop root stocks and put out leaves, the Apollo seedlings were stunted and had poor root growth.

The main thrust of the research was to examine plants at the genetic level. This allowed the scientists to recognise which specific environmental factors evoked the strongest genetic responses to stress. They found that most of the stress reaction in all the Apollo seedlings came from salts, metal and oxygen that is highly reactive (the last two of which are not common in terrestrial soil) in the lunar samples.

The three Apollo samples were affected to different extents, with the Apollo 11 samples being the slowest to grow. Given that the chemical and mineralogical composition of the three Apollo soils were fairly similar to each other, and to the terrestrial sample, the researchers suspected that nutrients weren’t the only force at play.

The terrestrial soil, called JSC-1A, was not a regular soil. It was a mixture of minerals prepared specifically to simulate the lunar surface, and contained no organic matter.

The starting material was basalt, just as in lunar regolith. The terrestrial version also contained natural volcanic glass as an analogue for the “glassy agglutinates” – small mineral fragments mixed with melted glass – that are abundant in lunar regolith.

The scientists recognised the agglutinates as one of the potential reasons for lack of growth by the seedlings in the Apollo soil compared to the terrestrial soil, and also for the difference in growth patterns between the three lunar samples.

Agglutinates are a common feature of the lunar surface. Ironically, they are formed by a process referred to as “lunar gardening”. This is the way that the regolith changes, through bombardment of the Moon’s surface by cosmic radiation, solar wind and minuscule meteorites, also known as space weathering.

Because there is no atmosphere to slow down the tiny meteorites hitting the surface, they impact at high velocity, causing melting and then quenching (rapid cooling) at the impact site.

Gradually, small aggregates of minerals build up, held together by glass. They also contain tiny particles of iron metal (nanophase iron) formed by the space weathering process.

It is this iron that is the biggest difference between the glassy agglutinates in the Apollo samples and the natural volcanic glass in the terrestrial sample. This was also the most probable cause of the metal-associated stress recognised in the plant’s genetic profiles.

So the presence of agglutinates in the lunar substrates caused the Apollo seedlings to struggle compared with the seedlings grown in JSC-1A, particularly the Apollo-11 ones. The abundance of agglutinates in a lunar regolith sample depends on the length of time that the material has been exposed on the surface, which is referred to as the “maturity” of a lunar soil.

Very mature soils have been on the surface for a long time. They are found in places where regolith has not been disturbed by more recent impact events that created craters, whereas immature soils (from below the surface) occur around fresh craters and on steep crater slopes.

The three Apollo samples had different maturities, with the Apollo 11 material being the most mature. It contained the most nanophase iron and exhibited the highest metal-associated stress markers in its genetic profile.

The importance of young soil

The study concludes that the more mature regolith was a less effective substrate for growing seedlings than the less mature soil. This is an important conclusion, because it demonstrates that plants could be grown in lunar habitats using the regolith as a resource. But that the location of the habitat should be guided by the maturity of the soil.

And a last thought: it struck me that the findings could also apply to some of the impoverished regions of our world. I don’t want to rehearse the old argument of “Why spend all this money on space research when it could be better spent on schools and hospitals?”. That would be the subject of a different article.

But are there technology developments that arise from this research that could be applicable on Earth? Could what has been learned about stress-related genetic changes be used to develop more drought-resistant crops? Or plants that could tolerate higher levels of metals?

It would be a great achievement if making plants grow on the Moon was instrumental in helping gardens to grow greener on Earth.