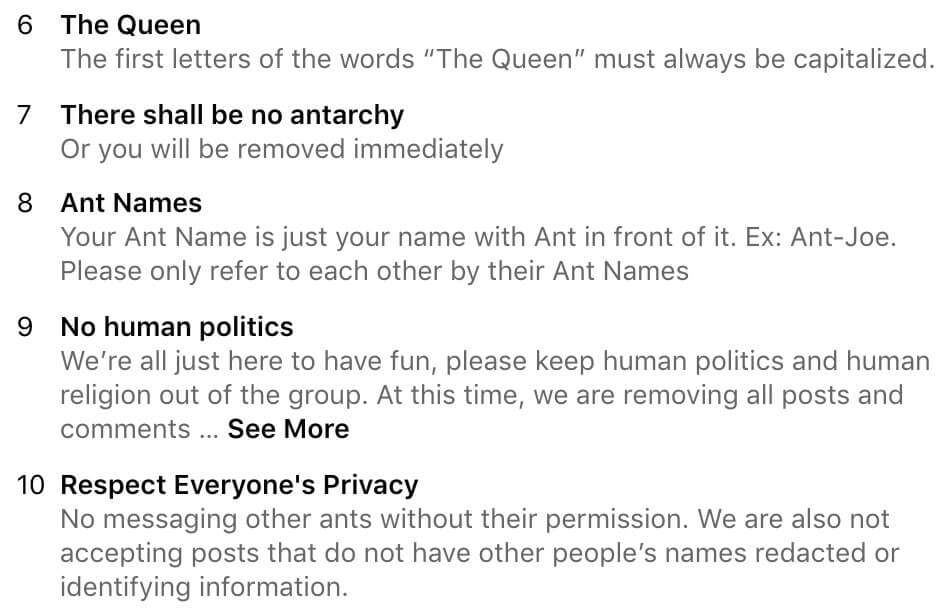

A friend of mine made me aware of a Facebook group called: a group where we all pretend to be ants in an ant colony. According to the group’s ‘About’ section, the members are ants, “worship The Queen and do ant stuff. ” Founded in June 2019, the group began to receive mainstream publicity after a viral tweet and has now over 1.9 million members.

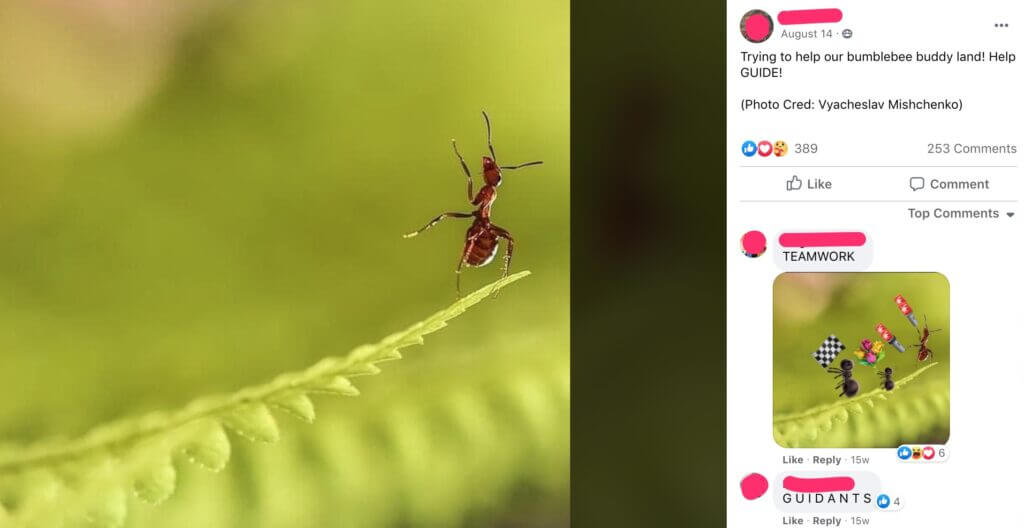

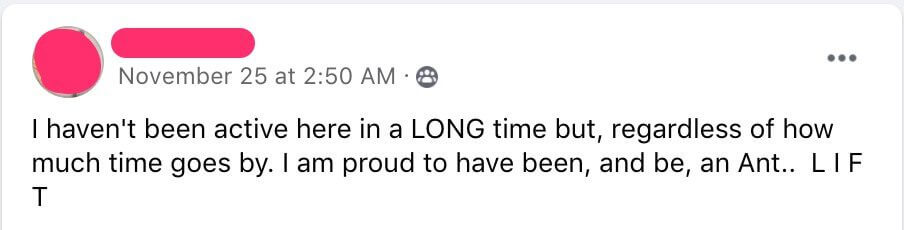

Almost exclusively, the group’s discussion activity consists of a member – an ant – posting a picture of ants, food, signs, the ground, natural enemies (e.g. anteaters, humans) with the caption calling for help, advise, a meeting at a specific tunnel in the anthill, or sacrifices (for The Queen). The common responses of the group members/the colony include calls for: L I F T; I N S P E C T; B I T E; A T T A C K; O B E Y; B R I N G T O Q U E E N; D I G; or fitting puns, such as illustrated below.

While the preceding description is an accurate representation of the group’s activity, the overarching dynamics and interactions are best understood through a plethora of examples, such as those given by TikTok creator @kopke613, who also helped popularize the page.

This group, where members are roleplaying as ants in an ant colony, is the most popular out of a variety of Facebook groups all of which have the same undertones and appear to be representing a yet unnamed phenomenon or new meme genre. A few other notable examples of this include groups where people pretend to be: Karens, Tories, boomers, Sims, emotionally stable, pieces of bread, as well as ‘anteater and attack the colony of ants’ – the last one clearly emerging as a direct response to the rise of the ant colony Facebook group. The members are predominantly from the millennial and ‘Z’ generation and utilize the roleplay to indirectly criticize and lampoon, as in the case of the first three examples. Other groups, however, are apolitical and appear to be solely for roleplaying purposes.

What does this mean?

When my friend first told me about the ant colony group, I assumed it was simply the Internet’s response to being locked up due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Thus, I assumed these groups to be an example and expression of what Kaye and Johnson argue to be the Web’s ability to satisfy escape needs. After having attended several sociological lectures, and learning that these groups started before any restrictions were implemented, however, I began to ponder whether this phenomenon is perhaps beyond being a simple case of escapism and instead is a new form of collective identity play. Is this what is at the bottom of this, or is it digital larping, or maybe merely a case of meme-ing? Determining this goes beyond the scope of this blog post, yet, I will aim to present the arguments for each concept.

Identity Play

In the early days of the still text-based Internet, identity play was made possible as the medium allowed users to “switch genders, appearances, sexual orientation, and countless other usually integral aspects of the public self.” Thus, Internet users were able to disembody themselves and their identity. Turkle, who helped shape the academic thinking surrounding identity play argued that “virtual identities [are] evocative objects for thinking about the self”. This is certainly the case when examining the group ‘where we all pretend to be emotionally stable’ but also the one ‘where we all pretend to be pieces of bread’. As peculiar as it might appear at first glance, answers on a post asking “what kind of bread are you?” evoke a certain degree of understanding in us: (1) about what that kind of image that person is trying to project, and (2) how they perceive themselves.

What underpinned this was the notion of the Internet as inherently anonymous and exclusively virtual. Nowadays, however, this is no longer the case as the Internet has developed to be inherently embodied, public, and intertwined with offline life: the majority of Internet users have their real name associated with their various profiles. Furthermore, they have public profiles on Instagram, where their faces are visible, on LinkedIn, where their occupational career is traceable, or on Facebook, where their life moments and friendships are laid out.

In the case of these Facebooks groups, members are posting under their ‘real’ profiles – yet, they are still maintaining to be what the group is roleplaying to be. Thus, an important question arises: Why?

LARP and Memes

A convenient fallback response to this is that the members of these groups are merely participating in some form of trolling – that is to say, they are just ‘playing around’. Some, like Manavis, have deemed this to be the case for these Facebook groups, arguing that they are just platforms for digital ‘live-action role-playing’ (LARPing). Hence, she is gamifying the groups and thus distancing the collective roleplaying from being connected with identity play.

When extending Tuters’ work on digital far-right cultures to these considerably less decisive Facebook groups, at the core of it remains the ironic slogan ‘teh Internet is serious business’. That is to mean the opposite: the Internet is not serious business, should be had fun with, “and anyone who thinks otherwise should be corrected and is, essentially, undeserving of pity.” This understanding of trolling and LARPing can be positioned alongside with what Limor Shifman calls ‘meme literacy’. While some memes, forms of trolling, or playing around can be understood by almost everyone, others require detailed knowledge about digital subcultures in order to be fully understood.

In her book ‘Memes in Digital Culture’, Shifman connects Jean Burgress’work on vernacular creativity to memes, contending that Internet memes are “everyday innovative and artistic practices that can be carried out by simple production means”. This would situate these Facebook groups into meme culture as their creation, posts, as well as comments, can be deemed to be both creative and innovative. This is supported by Manavis, who argues that a key driver behind these groups is the desire of young people to show off their creativity. Moreover, the maintenance and reproduction of the meme is rather simple: for the poster, it’s simply a Google image search of something related to ants, while the commenter, who is guided by the predetermined vocabulary of the group, simply has to come up with a fitting, funny response.

Shifman goes on to suggest the main meme genres of our current digital society. With this, she does not limit them exclusively to the online sphere, thus moving beyond earlier research’s focus on the binary separation of the online and offline realm. Shifman brings forth nine main meme genres that range from Reaction Photoshops to Flash Mobs, from LOLCats to Rage Comics. These genres can be divided into three overarching genre categories: First, those that are based on the documentation of “real-life” moments, such as photo fads and flash mobs, which are “anchored in a concrete and nondigital space.” Second, those that involve the explicit manipulation or remixing of mass-mediated visual content, like Photoshop, misheard lyrics, lipsynching or recut trailers. While the ‘a group where we all pretend to…’ doesn’t appear to fit into any of the specific Internet meme genres, it does appear to fit into the third meme sub-category, which focuses on “a new universe of digital and meme-oriented content”, according to Shifman. These genres encapsulate the development of meme literacy, as only those with detailed knowledge about contemporary pop-culture and digital subcultures ‘get it’.

Finally, the opening question remains: why are my friends pretending to be ants? Is it to escape the dread of the current pandemic, to troll and be on the ‘in’ of current meme culture, to play and explore their identity, or possibly to show off their creANTivity? Most likely, it is the combination of all of the above.

Authors’ Note

All images in this post were produced by the author. As the members of the featured groups did not agree to be analysed or featured in this post, their profile names, as well as pictures, have been blurred out. In the case of the ant colony, this adheres to the group’s community rules, which call for the respect of everyone’s privacy. It should be noted, however, that although some of these Facebook groups are private – that is to say one has to request admission or agree with the group rules before getting accepted – most of them have between 1k-30k members. Moreover, the Facebook groups appear as though they appreciate the increased recent spotlight on them with some highlighting and tagging posts that feature articles written about them (in the case of the ant colony, this tag is named ‘PublANTcity’). Thus, for the purpose of this unofficial, non-peer-reviewed blog post, it is reasonable to assume that some degree of communally accepted openness prevails, which allows for this kind of non-invasive analysis.

Bibliography

- A group where we all pretend to be anteater and attack the colony of ants [Facebook]. Available Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/3435216359828019 [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- A group where we all pretend to be ants in an ant colony [Facebook]. Available Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1416375691836223/ [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- A group where we all pretend to be boomers [Facebook]. Available Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/345685006108855/ [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- A group where we all pretend to be emotionally stable [Facebook]. Available Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/2556316984634260 [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- A group where we all pretend to be karens [Facebook]. Available Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/523927875138719/ [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- A group where we pretend to be sims [Facebook]. Available Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/862153987625552/ [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- A Group Where We All present To Be Tories [Facebook]. Available Online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1140675579630137/ [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- Baym, N. (1998). The emergence of on-line community. In S. G. Jones (Ed.), New Media Cultures: Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting computer-mediated communication and community (pp. 35-68). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781452243689.n2

- Kaye, B. K. & Johnson, T. J. (2004). A Web for All Reasons: Uses and Gratifications of Internet Components for Political Information, Telematics and Informatics, [e-journal] vol. 21, no. 3, pp.197–223, Available Online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0736585303000376 [Accessed 29 November 2020].

- Know Your Meme. (2020). A Group Where We All Pretend to Be Ants in an Ant Colony, Available Online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/sites/a-group-where-we-all-pretend-to-be-ants-in-an-ant-colony [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- Kopke613 (@kopke613) (2020). I have officially lost my mind in quarantine [Twitter] 18 April. Available Online: https://www.tiktok.com/@kopke613/video/6817081011357207814?lang=en [Accessed 29 November 2020].

- Manavis, S. (2019). Why Young People Are Turning to Online Live-Action Roleplay, New Statesman, Available Online: https://www.newstatesman.com/science-tech/social-media/2019/07/millennials-gen-zers-baby-boomer-facebook-turning-digital-online-live-action-roleplay-larp [Accessed 30 November 2020].

- Mangkukulam, M. [@agasramirez] (2020). Quarantine Day 31: I joined a Facebook group where we all pretend to be ants in an ant colony [Twitter] 15 April. Available at: https://twitter.com/agasramirez/status/1250264279711793153 [Accessed 30 November 2020].

- Shifman, L. (2015). Memes in Digital Culture, [e-book] Boca Raton; London: CRC Press, Available Online: http://www.dawsonera.com/depp/reader/protected/external/AbstractView/S9780262317696 [Accessed 2 December 2020].

- Tuters, M. (2019). LARPing & Liberal Tears: Irony, Belief and Idiocy in the Deep Vernacular Web, in M. Fielitz & N. Thurston (eds), Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right: Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US, Bielefeld, Germany: transcript Verlag.