Key Takeaways:

- We are in the midst of a battle for our attention.

- Faced with the kinds of findings that arose from our research, it is easy to be nostalgic about a past that existed before the digital revolution.

- Despite the generational stereotypes of teenagers glued to their screens, a majority of middle-aged people said they struggle with this too.

- Our ability to focus varies hugely depending on the individual and the task at hand.

- In other words, what if those lamenting a crisis in attention are not wrong, but only represent part of the picture?

- There is no question that we need to figure out how to live better with the “attention economy”, and that the monetisation of our attention is challenging us in fundamental ways.

We are in the midst of a battle for our attention. Our devices have hijacked our brains and destroyed our collective ability to concentrate – to the extent that we’re even seeing the emergence of a “goldfish generation”. That, at least, is the story that’s increasingly being told. But should we be paying attention to it?

Journalist Johann Hari’s new book, Stolen Focus, has just joined a chorus of voices lamenting the attention crisis of the digital age. His and other recent books reflect, and perhaps fuel, a public perception that our focus is under attack.

Indeed, in new research by the Policy Institute and Centre for Attention Studies at King’s College London, we found some clear concerns.

Faced with the kinds of findings that arose from our research, it is easy to be nostalgic about a past that existed before the digital revolution. But new technologies have been blamed for causing crises of distraction long before the digital age, so how should we respond to the current challenges?

An attention crisis?

We surveyed a nationally representative sample of 2,093 UK adults in September 2021, asking about their perceptions of their attention spans, their beliefs in various claims about our ability to focus, and how they use technology today.

Half of those surveyed felt their attention spans were shorter than they used to be, compared with a quarter who didn’t. And three-quarters of participants agreed we’re living through a time where there’s non-stop competition for our attention from a variety of media channels and information outlets.

The distraction caused by mobile phones in particular appeared to be a real issue. Half of those surveyed admitted they couldn’t stop checking their phones when they should be focusing on other things – and this wasn’t just an issue for the young. Despite the generational stereotypes of teenagers glued to their screens, a majority of middle-aged people said they struggle with this too.

And although many recognised that they spent a lot of time on their phones, they still hugely underestimated just how much. The public’s average guess was that they checked their phones 25 times a day but according to previous research, the reality is more likely somewhere between 49 and 80 times a day.

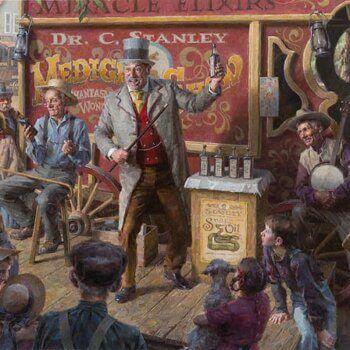

There has long been a worry about the threat to attention brought by new cultural forms, whether that’s social media or the cheap paperback sensation novels of the 19th century. Even as far back as ancient Greece, Socrates lamented that the written word creates “forgetfulness in our souls”“. There has always been a tendency to fear the effects new media and technologies will have on our minds.

The reality is we simply don’t have the long-term studies that tell us whether our collective attention span has actually shrunk. What we do know from our study is that people overestimate some of the problems. For example, half of those surveyed wrongly believed the thoroughly debunked claim that the average attention span among adults today is just eight seconds, supposedly worse than that of a goldfish. There’s not really any such thing as an average attention span. Our ability to focus varies hugely depending on the individual and the task at hand.

Attention snacking

It’s also important to not overlook the many benefits that technology brings to how we live. Much of the public surveyed recognised these, so while half thought big tech and social media were ruining young people’s attention spans, roughly another half felt that being easily distracted was more to do with people’s personalities than any negative influence that technology may or may not have.

That aside, is “dispersed” attention always a bad thing?

Two-thirds of the public in our study believed switching focus between different media and devices harms our ability to complete simple tasks – a belief confirmed by psychological studies. Intriguingly, half of the public also believed multi-tasking at work, switching frequently between email, phone calls, or other tasks, can create a more efficient and satisfactory work experience.

So what if we explore the benefits of distraction as well as the negative impacts? Might we find a more balanced picture in which distraction is not always in and of itself a bad thing, but a problem in certain contexts and productive in others? In other words, what if those lamenting a crisis in attention are not wrong, but only represent part of the picture?

For all the challenges we experience in having our attention toggle between tasks, in some scenarios, this might help refresh the mind, keep us alert, and stimulate brain connections and creativity. Unified attention may be an ideal, but it may not always be a realistic good for the type of animal that we humans are.

We hear about the benefits for the body of “exercise snacking” or circuit training, so perhaps we need to ask how we might harness the potential benefits for the mind of “attention snacking”. The brain is, after all, a physical organ.

There is no question that we need to figure out how to live better with the “attention economy”, and that the monetisation of our attention is challenging us in fundamental ways. However, our electronic gadgets are not going away and we need to learn how to harness them (and the distractions they pose) for individual and social good.

Our attention has always been the only real currency we have, and for that reason, it has always been fought over; this is not a new problem, but in the digital age it is taking new forms. We need a better response to this situation – one that understands the risks but is also bolder in asking questions about the opportunities.