Wikipedia defines the Precautionary Principle as “a broad epistemological, philosophical and legal approach to [ideas] with potential for causing harm when extensive scientific knowledge on the matter is lacking. It emphasizes caution, pausing and review before leaping into new [behaviors] that may prove disastrous. Critics argue that it is vague, self-cancelling, unscientific and an obstacle to progress.”

Its opposing counterpart, according to an article published this week in The Atlantic, “is something like Epistemic Optimism: We don’t know enough, and we should always try to learn more.”

Glass Half What?

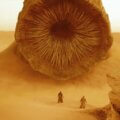

These two principles essentially represent both sides of the “glass half empty or glass half full” argument. The familiar expression uses a compelling image — a drinking glass containing equal parts water and air — to illustrate that when people share an experience, they invariably see it quite differently; and that further, this leads to a wide range of conclusions about the event — and the world — that are built on perceptions, not reality, and that regardless, most of us will insist they are facts.

Just look at the stomach-churning political landscape in the United States. Half of the country lives one “reality”, in which media is used to pump out dystopic propaganda, specious (fake!) science is wielded to manipulate and ruin lives, governments represent threats to precious freedoms, and the only thing standing in the way of societal collapse are guns. The other half lives another “reality” altogether, in which media is the final defense against despotism, science offers our greatest hope of survival in spite of ourselves, governments temper the vagaries of unchecked greed (aka freedom), and guns are the only thing standing in the way of societal collapse.

It’s astounding.

A similarly stark distinction can be drawn as it relates to every person, institution, religious and political system.

Danger or Opportunity?

In the end, our predisposition toward either the Precautionary Principle or Epistemic Optimism greatly influences two things. The first of these is whether we view the world as inherently threatening, or inherently full of untapped potential. The second is whether our world view ossifies as the result of our resistance to change, in a form of self-amplifying inertia, or evolves along with new inputs, in a form of optimistic potentiality.

Pandemic Playgrounds

Nowhere has this stark difference in how we each view the world played out more loudly over the past year than on the pandemic front. As I’ve written extensively, I have ping-ponged bi-weekly between two inherently incompatible — irreconcilable — realities: those of New York City, where 32,140 lives have been lost, or 1 out of every 262 people; and of Ontario, where 7,735 lives have been lost, or 1 out of every 1,883 people. Said another way, NYC has suffered over seven times the deaths of Ontario, per capita. For the lucky who haven’t died, in NYC a staggering one in eight jobs have been lost, and moreover, the unemployed lack a robust governmental safety net to blunt the impact of those losses. By stark contrast, in Ontario, one in twenty-one jobs have been lost, and for those impacted, a muscular government subsidy program called the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), has shifted much of the financial burden from out of work individuals to the government, to enable them to subsidize and/or rehire workers they can no longer afford. CEWS taps out at $56,000, per employee.

Said another way, seven times more people have died due to COVID-19 in NYC than in Ontario, per capita; and in addition to this, three times moreworking adults have lost their jobs there as well, per capita, without the safety net that Ontario has set up for its own.

Given the numerical facts, one would expect to find human behaviors on display in each place that are in line with the statistics, right? Meaning, we’d expect New Yorkers to be rioting and murdering one another the way they did on the “mean streets” of the 70’s, the last time the unemployment rate was as high as it is now. At the same time, one would expect to see Torontonians’ blood pressure on an even-keeled simmer, due to the blunted impact of the life and job losses there, by the grace of government.

And yet: to experience both places on the ground, as I have — like a tennis match — back and forth every two weeks for the past 14 months, is to experience something that defies logic and even definition, if not for an understanding of both the Precautionary Principle and Epistemic Optimism.

That’s because it is only by understanding that each mindset — glass half empty or half full — has been fused into each culture, that it makes any sense that New Yorkers are calmly going about their (fully masked) days with a shrug as though nothing material has changed, while (for some reason less masked) Torontonians are at the psychological breaking point, fearing the imminent collapse of their society.

In New York City, the streets throng. Crime doesn’t feel — truly — any worse than it did pre-pandemic (and certainly nothing like my memory of the crime-infested 70’s thru early 90’s); and life, with relatively minor exceptions, continues apace, unabashed. Restaurants teem, street life is rich, subways are packed, and the city that never sleeps is now taking an occasional nap, but otherwise burns much of its midnight oil, still.

Most importantly, no one looks at one another any differently than they did last year. Meaning, New Yorkers’ inherent curiosity, and predisposition toward social integration and interaction, remain unabated. Epistemic Optimism is alive and well in The Big Apple.

In Toronto and even rural Ontario, by contrast, the Precautionary Principle rules supreme. Not content with 2m (6-foot) distance, Ontarians regularly stop in their tracks the moment I’m within 20 feet of them, often crossing streets just to avoid being anywhere near another person. When the sacred 2m force field is breached, it too-often unleashes not only inevitable admonitions about how my actions are endangering the public, but more troublingly, blistering and aggressive tirades. I’ve been the victim of more than a few of these — some in front of my children.

Ontario’s most recent policy, enacted this past Monday, not only shuts down all commercial enterprises apart from food and medicine sources, but also — inexplicably — public amenities like golf courses, among other outdoor salves to frayed nerves. Worse still, one is now forbidden from gathering socially with anyone outside of one’s nuclear family — even outside. The exact wording goes, “[Ontario] has prohibited all outdoor social gatherings and organized public events, except for with members of the same household.”

To say it again: Ontarians are now forbidden from enjoying outdoor activities, at the outset of Springtime, in an environmental context where transmission rates are now proven to be close to zero, with a few basic mitigations.

In fact, one of the world’s leading experts on viral transmission, Linsey Marr, believes that the world has gone too far in regulating outdoor activity. She says, “I think we should focus on the areas that have highest risk of transmission, and give people a break when the risk is extremely low.”

A break. She’s talking about mental health there.

She advocates a “two out of three” rule: if one meets two of three primarysafety criteria, then it should be good enough for any person or government. She leads her own life this way. The three criteria are: being outdoors; socially distancing by 2m (6ft); and wearing a mask.

Said another way, if you’re outdoors and 6 feet apart, not only should you be allowed to do that, but you don’t even need a mask. This, from the world’s reigning expert.

In emotionally battered Toronto, a few intrepid journalists are imploring readers to “change the narrative on outdoor transmission”.

Policy is not reflecting reality, according to the article. In fact, in a clever act of legerdemain, the author ties being outdoors to reduction in risk, when she writes: “being outdoors is much safer, and may prevent transmission indoors.” Meaning, the more that people spend time in low-to-no-risk environments, not only will their mental and physiological health improve, but the less time they’ll therefore spend in high-risk environments.

She’s right; and it is also a clear example of Epistemic Optimism, on display.

Most Ontarians feel very differently from her. They live in a world where people are now seen as biological weapons, risk is everywhere, and the best thing we can do — absent 100% proof to the contrary — is to live by the spirit of my own father’s favorite expression, and my least favorite: “When in doubt, duck.”

As a result, the sky is falling in Ontario.

In New York City, no one has time to worry about the sky, or what it’s doing. They’re too busy scoring reservations at reduced-occupancy restaurants or rooftop bars, or going about the daily business of exercising, shopping and working.

In fact, it’s somewhat astounding to me that with such a massive rate of unemployment, the city isn’t more dangerous, and the mood isn’t darker. Yes, there are more visible homeless people, but they are acting benignly. Yes, signs everywhere urge us to wear masks, which nearly 100% of residents do. But by and large, to be in NYC is largely as it always was, which is — fundamentally — a seriously exciting place to be.

In Ontario, the mood is much, much darker. Upon entry into the country, one is literally swarmed by officers and public health officials who warn you that you represent a danger to the public. They mandate the completion of multiple forms that allow them to assess and track you for the ensuing two weeks. They corral wide-eyed travelers through a gauntlet of immigration and public health officials and procedures, before sending them into converted airport hotels to quarantine, jail-like — where your door is opened just 3x/day, for meal delivery — until they’ve been deemed safe enough (2 tests later) to complete their 2-week quarantine at home. During that second phase, they can count on visits from the police, health officials and/or the RCMP (the Canadian FBI). Ontario’s is a belt, suspenders, staples, screws and duct tape approach to ensuring nothing leaks through from an inherently dangerous world.

Duck, indeed.

Upon arrival at a New York area airport, by contrast, there is none of it. Zero.

How is this possible?

Final Thoughts

This piece is neither about condoning activities that result in an “acceptable” death toll; nor is it advocating flagrant disregard for Law. One cannot argue about things about which people are emotionally charged, and invested.

What I am trying to point out is that municipal and national narratives — towards places and communities — are incredibly powerful, and that they shape public attitudes in dramatic fashion. New Yorkers, first and foremost, believe themselves to be tough, resilient and resourceful. Americans at large consider themselves the consummate fighters. TV movies and politicians alike continually reinforce these things, in NYC and nationally. By stark contrast, Torontonians believe the highest order of public good is the adherence to rules, and if the rules say it, then by golly, they’re gonna do it! “Toronto the Good” is how I recently learned Montrealers have labeled Torontonians, for more than a century. And Canada itself is supremely focused on risk mitigation. Its inherent conservatism served it well in the 2008 housing crisis, where it escaped the brunt of the fallout Americans remember. It has branded itself accordingly.

It’s not unfounded to extrapolate here, and call New York City a place of Epistemic Optimism: “If I can make it here; I can make it anywhere”, as the famed Sinatra song goes. In Toronto, for four years now — long before COVID hit us — I have experienced a city deeply committed to the Precautionary Principle. I’ve written stories about why I think that is: its conservative Scottish roots; its banking-centric business engine (risk risk risk!); and its one million risk-averse Montrealers (out of 3,000,000) who fled culturally torn Quebec to find safe haven in a more stable environment.

Like attracts like.

And so, science has little to do with either city’s attitudes. What drives them, I’d propose, is each one’s municipal and national narrative.

In the meantime, multiples more people are suffering job and life loss in NYC than in Toronto; and yet they are buoyed by an inherent optimism: ‘We’ve been here before; and we’ll be here after’. Said another way, New Yorkers are focused on the upside of social engagement and the eventual end of the pandemic. They are looking at the water that remains in the glass, and are grateful for it. Torontonians, on the other hand, can see only what’s going wrong, and focused on what more could go wrong. They are looking at the air in the glass that used to be water, and freaking out.

So, it is to be expected that something like golfing is now prohibited, much as the province closed its ski hills earlier in the winter. It’s nonsensical; not one recorded person out of the 150 million who have contracted the virus worldwide, nor the 3 million who have succumbed to it, has done so in a sparse outdoor environment. In fact, just 6% of all cases have been contracted outdoors, all of them at densely populated rallies or entertainment venues.

But people who see one another as weapons would rather overreact than underreact. Risk, after all, is risk; and the acceptable amount of risk in Toronto approaches zero.

The bottom line here is that Torontonians’ attitudes are making them miserable, and fanning the flames of burnout and mental illness — not to mention additional economic losses — while they face yet another lockdown at the hands of a government and citizenry committed to the Precautionary Principle. New Yorkers’ attitudes are doing the opposite: they are seizing their day and making lemonade out of lemons, taking over streets that now teem with restaurants and vehicle-free block parties; and swarming public outdoor spaces that those who follow the science that people like Linsey Marr have attempted to teach of late, know are their best bet of maintaining mental health and the vital pulse of an unabashedly, epistemically optimistic city.

And that is the lesson here to be had.