Terry Mollner — whose Calvert Impact Capital funds are the world’s largest, at $9 billion (or $12 billion, depending on what source you cite) — is one of the great pioneers of a new economy based on meaningful relationshipsand the common good — a conceptual framework that is increasingly called ‘Game B’ these days, as an alternative to the prevailing global model of ‘Game A’, zero-sum, win-lose capitalism. Mollner’s two guiding lights are decidedly at odds with the principles that drive business today. In fact, not only are they conspiciously absent in models of corporate governance, to many, they constitute sheer economic heresy. To Game A’ers, internal, non-client relationships and the common good are deep distractions from what really matters — profit — and all of its tributaries—the things we take the time to actually measure—like market share, backlog, growth, productivity, efficiency, and of course, #winning. In corporations, words like ‘wellness’ are proudly marketed to potential employees. But when you consider that large (20,000+) employers spend less than $800 per employee on wellness incentives and programs, according to healthpayerintelligence.com, and that the wellness industry is a $6 Billion affair in the United States—where more is spent per capita than elsewhere, making wellness spending equal to just three hundredths of one percent of the $21.5 Trillion US economy, according to investopedia.com—wellness is still largely — sadly — little more than a salve, applied in order to keep workers happy enough that they will generate increasing profits for the owners, and healthy enough that employers see some financial return on their investment. In fact, according to health tech company helloheart.com, wellness spending is applied to one of two categories, and that companies see a $0.50 ROI on every dollar spent on ‘lifestyle management’, and a $3.80 ROI—a fourfold return—on ‘disease management’. So wellness spending is both minimal and good for the bottom line; and when put together, these two statistics betray just how little employees’ mental and physical health figures into corporate America’s balance sheet, and focus. With regard to the common good, it’s better, but there is significant room to grow. The Harvard Business Reviewwrites that Fortune 500 companies spend a total of $20 Billion on corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, of their $13.7 Trillion in combined revenues (they collectively comprise 2/3 of the US GDP). That means that the common good receives one-and-a-half hundredths of one percent of Fortune 500 revenues.

I’m not clapping.

So back in 1973, Mollner set out to create an alternative — an antidote, really — to a business model he was convinced would eventually drive the planet and its people to ruin, if left unchecked. His goal was to prove that such a thing could exist and be “fully integrated into the modern world,” as it is, today. As he writes in the astounding article, Mondragon: The Loving Society That is Our Inevitable Future, “I had been searching the globe for years for a Relationship Age society,” and adds, “I had never expected to find such a mature and comprehensive example,” hiding in plain sight.

He did. And what he found has been operating that way since its inception at the height of World War II, some 75-plus years ago, birthed in war-torn Western Europe, under the nose of Spain’s great dictator, Francisco Franco. That was long before it became the dominant association of cooperative businesses in Spain. Today, Mondragón — named after the town in which it was founded, and centered — is comprised of over 30,000 members. Collectively, they are Spain’s top producer of industrial machinery and major home appliances, lead the way in heavy construction, furniture production, farming and high technology, and created Spain’s computer chip industry. Their profitability is twice that of the average Spanish corporation, and worker productivity is higher than anywhere else in the country. Even more amazingly, it operates its own banks, schools, health insurance companies and food stores, in an ecosystem of community services and relationships. And tellingly, their Entrepreneurial Division, which provides venture capital to new ‘relationship cooperatives’, boasts close to a 100% success rate. When we set that against the American average of 80% failure within five years, it’s nothing less than astounding.

Put in a single sentence, their mantra is: relationships for life. They approach all business activities through this lens, not just because the owner-members are tied to their investments — people and capital — for life, but because of the inherently tribal feeling they all share that they are family. They feel this way, because frankly, they are treated this way, from their education to their health to their training to their work-life balance to the literal investment and ownership stake they all have in their own work concern.

In short, consistent with the title of Mollner’s article, love drives business in Mondragón.

What a strange concept: a business built on love. But that’s exactly what it is. Mondragón, the business enterprise, is a modern community that was founded on infinite values, like love, family, connection, honesty, relationships, trust, respect, safety, communication and tolerance, by a young priest named Don Jose Maria Arizmendiarrietta. For Don Jose Maria, people came before things.

When it came to making decisions, he was known mostly for the following question, “How can we do this in a way which works fully for those in the enterprise and those in the community rather than for one more than the other?” To him, the notion that there needed to be a loser in any transaction was a shortcoming of imagination.

Just a few concrete examples of how it works:

- Every member of the cooperative is also an owner. If they don’t have enough capital for their initial investment (equivalent to $15,000 USD), it’s loaned to them, and they pay it down, with their work contributions.

- Loans to finance new ventures that members incubate are made by the conglomerate’s own financing arm, until the investment succeeds. With every challenge faced and not met, the interest rates lower, not raise. If the fledgling business is in deep enough trouble, the bank will donate capital to the business. Eventually, most businesses succeed, because they have been supported deeply, until they do. Said another way, a parent doesn’t abandon its child until it can stand on its own two feet.

- Half of all profits made within the cooperatives go directly to the owner-member-employees; however, beyond a guaranteed 6% interest dividend, the remaining profits are reinvested in their individual “internal capital accounts”, there to grow with the continued success of the companies.

- Beyond this, ten percent of all cooperative profits are earmarked for charity (against a 2% average in the United States).

- Unemployment insurance pays 80% of take-home pay in the case of a layoff, and a pension plan pays 60% of the same, until death — on top of their cooperative profits.

- The Board of Trustees is fully comprised of cooperative members.

It goes on.

The larger arc of this story is that a new model of business is emerging — one that stands at odds with what Mollner refers to as the Material Agestructural priority order of “capital, then product, then managers, then workers”. In a Relationship Age company, it’s the opposite: workers, then managers, then product, then capital. Which is another way of saying:

“People before things.”

.

No shortage of Game B efforts are underway today — a ‘skunkworks’, of sorts, within the prevailing model of business. I belong to one such community — on Facebook — where ideas and initiatives are shared freely, because the driving goal of this new work effort is for people to test new ideas that can improve or save lives, and let them proliferate as quickly as possible, without regard to whose hands craft a winning alternative. In other words, in Game B efforts, any idea that improves the outcome for people is a winning idea, whatever the commercial gain may eventually be, if at all.

I have no way of describing it other than to call this ‘altruistic behavior’, whose end goal is primarily the health of the collective — you know, people. It is a form of karmic confidence, advanced before it has been earned.

Game A

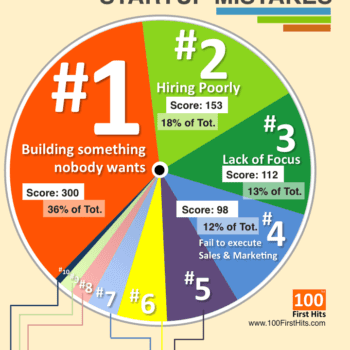

People are doing this because they understand that nearly every institution we have created over thet past 13,000 years has followed a Game A model of win-lose relationships and activities that place things (profit, really) before people (financial, physiological and emotional wellness), and in which people are primarily seen as tools for achieving economic (or military, or political) success.

We see this excessive attachment to money in every broken system today, from politics, which are largely run by lobbyists and corporate kickbacks, to agriculture, which continually squeezes—destroys, really—the Earth for profit, to healthcare, where access to services and drugs correlates with a sliding scale of financial means, to media, where the sole determinant of what gets airtime is competitive market share, to social interaction, which is increasingly transactional (everyone’s a brand, or a network connection), to education, which fewer and fewer can afford every year, and where here, too, money is the key that opens doors to both quality, and future networks. And of course, there’s the pandemic response itself, whose death toll is largely a reflection of the brokenness of these systems — systems that were highlighted by Ed Yong just two days ago, in his searing article for The Atlantic, How the Pandemic Defeated America. Yong is one of a few staff writers who have covered COVID-19 since it first descended upon us, speaking to more than 100 experts in a variety of fields. He lists countless economic drivers that have led to a rampant and unmatched death toll, in the United States: its “chronic underfunding of public health”; the “decades-long process of shredding the nation’s social safety net”; the “millions of essential workers in low-paying jobs” who “risk their life for their livelihood”; the “fealty to a dangerous strain of individualism”; the uprooting of “the planet’s animals, forcing them into new and narrower ranges that are on our own doorsteps,” from which relentless onslaught “viruses have come bursting out”; the defunding of China-based US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention specialists, and the American epidemiologist embedded within China’s own CDC; the profit-led “era of sick buildings” in which “pollutants and pathogens built up indoors”, leading to the sacrifice of “designing buildings for people”; the chronic understaffing of nursing homes — three in four!; the ‘economic protectionist’ policy of “reducing the influx of immigrants who make up a quarter of long-term caregivers”; the “national temperament that views health as a matter of personal responsibility rather than a collective good”; the “chronically strapped local health departments” who “lost 55,000 jobs — a quarter of their workforce” that resulted from “budget cuts”, which itself resulted from the fact that “the US spends just 2.5 percent of its gigantic health-care budget on public health”.

Cue: For the Love of Money—the theme song Donald J. Trump chose for his TV show, The Apprentice:

For the love of money

People will lie, Lord, they will cheat

For the love of money

People don’t care who they hurt or beatFor that lean, mean, mean green

Almighty dollar…Money money money mo-o-o-oney, money!

Yong writes, “This profit-driven system has scant incentive to invest in spare beds, stockpiled supplies, peacetime drills, and layered contingency plans.” He adds, “America’s hospitals have been pruned and stretched by market forces to run close to full capacity, with little ability to adapt in a crisis.”

The problems go beyond healthcare. One could argue that in a world driven by profit, the first thing to suffer is the people. Whether they lose their job, or are denied a living wage, or are forced to cram into ever-shrinking airline seats, or to move to cities in search of a better job to help ‘those back home’, or are forced to sue one another over what should be inalienable rights, denied, or are drinking polluted water caused by agricultural runoff (like Monsanto’s recent $10B payout)— or similarly, public dollars earmarked for pure sources that are averted to ‘save a buck’ (as in Flint, MI), or are finding themselves on the wrong side of the tracks, where prison, menial labor, slums or an early death await them, the Game A system that worships the almighty dollar — or yen, or yuan, or euro — is broken beyond repair, and the price for our transgressions is our final living breath.

Game B

The principle of Game B is simple. If you took any institution today and convened a panel of extremely bright and diverse thinkers and experts, asked them to re-imagine it, and instead of giving them carte blanche, you established two unyielding ‘rules’: that every decision had to advance so-called infinite values for which one cannot construct a loser (again, like community, integrity, honesty, empathy, humility… all of which are values reflected in a New Zealand study on the subject, here), and that business relationships were thought of as lifelong relationships, without end, then what emerged would look incredibly different from what exists today.

It wouldn’t take more than a single sentence, articulated with these principles, to see how each institution could be of more value to the collective. Let’s try it. The more broadly and deeply educated a population is, the more valuable its ideas become. The healthier it is, the more productively it can contribute. The better capitalized and supported an inspired idea is, the greater the energy that its passionate agents will bring to bear on the investment of time and energy, and the likelier it will succeed. The more a population feels they ‘own’ something, the greater their commitment will be, to it. The more trust that is built between leaders in different fields, divisions or businesses, the less distracted and polluted their focus will be, and the less combative / subversive / destructive, as well. The more integrated efforts are across the ecosystem of institutions that comprise a community, the better informed each will be, and the better decisions each will therefore make, as it affects the whole. The more tailored the flow of information is toward what matters most to our collective wellbeing, the more targeted our energies can be toward what will make the biggest difference. And the closer we feel to one another over the long term, the better collaborators we will be, toward the fulfillment of mutually understood, mutually beneficial and increasingly shared goals.

If it’s not obvious, I just described education, healthcare, banking, entrepreneurship, law, collaboration, media and social exchange, in that order.

We do this intuitively with our families — well, most of us do, anyway, and more likely would, if it weren’t for how some of us fight over… you got it: money, or access to limited resources. In Mollner-funded businesses, the common good trumps individual considerations, every time, to the point where it insists upon ‘reasonable’ profit caps, above which all excess profits are set aside and permanently managed for the common good.

In a 2014 article titled The Differences Among Socially Responsible, Impact and Common Good Investing, Mollner wrote about three existing models of corporation that aim to do something more than just generate profit. He writes that socially responsible (SR) companies do not abandon financial return as the driving priority of the corporation, while doing good; instead, they establish a ‘tolerance’ for investing in a form of “minimum socially responsible standards of behavior”. He adds that impact investing (II) goes a step further, focusing on “one or more good things that [the investing company] wants to perpetuate in society”. He then distinguishes both from common good investing (CGI), which he believes to be “the inevitable future of all investing”, because while SR is ‘less bad’ than conventional solely profit-driven companies, and while II is focused on some ‘external good’, only CGI begins with the foundational premise that the people doingthe work — i.e.: the primary value-creators — should be the primary beneficiaries of the fruits of their labor.

What a novel idea…

He explains the following: “If two people come together, they have two choices: they can compete or they can cooperate.” He cites lions, tigers and bears as apex competitors; while cooperation, he says, is “when all the parts give priority to the whole,” forming a “human society”.

Mondragón is just such a society, in which the greatest good is that which supports the community. As to the “full integration within the modern world,” the 30,000 people within Mondragón’s cooperatives are well-paid, all have equity ownership in their workplaces, enjoy a solid educational and healthcare support network, have greater job satisfaction and less turnover and failure, are supported in their business ideas, as budding entrepreneurs, are set up for life with a safety net that they contributed to, and outperform the rest of their own nation while doing it. Moreover, they’ve been doing this for three quarters of a century.

This isn’t the stuff of fairy tales.

Game B is sometimes called The Endless Game, or The Infinite Game,because any game that is enjoyable enough is one that its players wish to keep playing, rather than concluding. When we are focused on concluding a game, it is because it’s either boring, or we wish to win it. Not so for an endless / infinite game. Your children are one example of an endless game. We don’t invest time and effort in them and bid them adieu, never to be seen again. No. Rather, we invest in them because the relationship is its own reward — one that continues to pay dividends in the satisfaction that we have influenced one another for the better, and for the joy of continued interaction, and deepening richness. And sometimes, if we do a great job, they will prevent us from eating dog food when we’re old and peeing ourselves, and may even support us in our final years, if we cannot do so ourselves. I know that’s what my own family has done for one another, and we are not alone. We are the norm. We could say the same of our closest friends, as well as that co-worker or teacher or nurse who, with empathy, humility and selfless service, transformed our lives, and in the process, became a trusted advisor, or best friend, or even spouse.

I’ve seen that last one, too.

We are social creatures to our cores, and when we service our relationships, we enrich our lives, plain and simply. It is only when we corrupt our joy of connecting deeply with one another — whether it’s at the hand of competitive power plays, lack of respect or kindness, or conflicting views on what matters, or how to act in concert, without investing the time to resolve and align those things — that we devolve into animal behaviors, like the lions. It is the Machiavellian attitude, in which “a person is so focused on their own interests that they will manipulate, deceive, and exploit others to achieve their goals,” that leads to the breakdown in our foundational human relationships. It is this trait, along with its ‘cousins’, narcissism and psychopathy, that comprise what is known as the Dark Triad. And sadly, competition — which is not a necessary prerequisite to success, in any sphere — reinforces, and in fact greatly rewards, the cultivation and development of those dark traits.

In 1989, the Basque National Congress — the pre-eminent body of the autonomous Basque Country, technically still part of Spain, but largely self-governing — decided to officially adopt Mondragón’s “third way” as the method by which economic policy would be developed and administered. According to Mollner, “This may be the first nation in modern times to commit itself to the development of relationship economics.”

A century-plus earlier, in 1833, the widely circulated and as widely criticized Tragedy of the Commons was the brainchild of British writer William Forster Lloyd. In the Middle Ages, Britain was among one of many nations that held land and grazing rights ‘in commons’ — that is, freely available to, and often managed by, the communities that benefitted from, and contributed to, their upkeep. In his treatise, Lloyd speculated that this model led to the degradation of the land’s value, and bounty. He called this the tragedy of the commons. His musings stuck, and were used to undo a form of commonly held ownership rights that had been enjoyed for centuries by the citizenry. The truth, however, never supported his theories, and the fact is that commonly held, mutually managed & enjoyed resources continue to be held in common, today, though they admittedly comprise a tiny percentage of the world’s assets, or ‘businesses’. In Mongolia, Wikipediawrites, land degraded in shared pastures by about 9%, between 1992 and 1995, when a study was undertaken by the group Environmental and Cultural Conservation in Inner Asia. By contrast, in China and Russia, where state-owned pastures and privately held land were farmed, degradation ran at 75% and 33%, respectively.

Mongolia is not the only example, but it’s staggering to think that a shared asset whose modus operandi is to cultivate it in perpetuity — an ‘infinite’ game — can be from three to eight times more productive, and less destructive, than one in which an entity uses it to squeeze profit and consolidate power, damned be the asset — a ‘finite’ game.

We see this play out in deforestation, lakes of carcinogenic glyphosate, monocropping, over-fishing and wild species destruction.

Said another way, crassly, we are less likely to put a bullet in the head of someone we know well, or on whom we depend, than in that of a stranger whose life has no obvious material impact on ours, and whom we therefore don’t value.

The difference comes down to relationships.

In a relationship economy, connections are deeper, are more interdependent, and are invested for the long term — as in, forever. As a result, in a relationship-age company like any of the 95 of them that Mollner’s Calvert Impact Capital website features, or town, like Mondragón, or sector, like Mongolian agriculture, or nation, like the Basque autonomous region, the meaningfulness of our work and our relationships, and therefore, our lives, is amplified, greatly. When the group, or the community, or the government commits to one another, and develops a network of complementary activities, policies and structures to support the infinite relationships that contribute to, and benefit from, the combined energy of the people within it, everybody wins, and nobody loses.

To say it again: in a Game B economy, everybody wins, and nobody loses.

.

To suggest that the default human state is that of competition is to ignore 330 million years of human history, before the advent of permanent settlements, in which competition meant the death of the community, and therefore wasn’t tolerated in any way. If you’d like to read a powerful treatise on this subject, I highly recommend Christopher Ryan’s book, Civilized to Death: The Price of Progress. The conceit — lie — of competition is just that: something perpetuated by those who stood the most to gain by it, at the expense of the human community.

We are on the precipice of a Relationship Age, as Mollner posits, supported by a Relationship Economy. Luckily, enough smart, well-capitalized and business-as-usual-weary people are turning more and more attention to this subject, and incubating innovations to upend and replace the status quo. Our world, with its accelerating pressures, and a pandemic that has revealed — in a nanosecond — the stresses inherent in all of our Game A systems, is desperate for a rewrite. Game A has played itself out, and the price has been our health, as well as that of the planet.

And with luck, we won’t only live to see this Brave New World, but will be part of the solution in building it.

Bring on Game B!