Key Takeaway:

In 17th-century Europe, there was a debate about the existence of life on other planets due to the transition from a Ptolemaic view to a Copernican view. This led to the idea that if we were more like other planets and moons close to us that revolved around the Sun, they were more like Earth. This idea was supported by early modern science focused on God’s work in nature. The Copernican Bernard Fontenelle’s work on the plurality of worlds further developed this idea. However, there was a significant problem with the existence of intelligent beings on the Moon or planets, as they were uncertain if they were of “the seed of Adam.” John Wilkins and Bernard Fontenelle eventually adopted this solution, arguing that the existence of aliens threatened the credibility of the Christian story of the redemption of all humans through Jesus Christ. Modern “alienation” is the sense of being lost and forsaken in a godless universe.

Speculation about extraterrestrials is not all that new. There was a vibrant debate in 17th-century Europe about the existence of life on other planets.

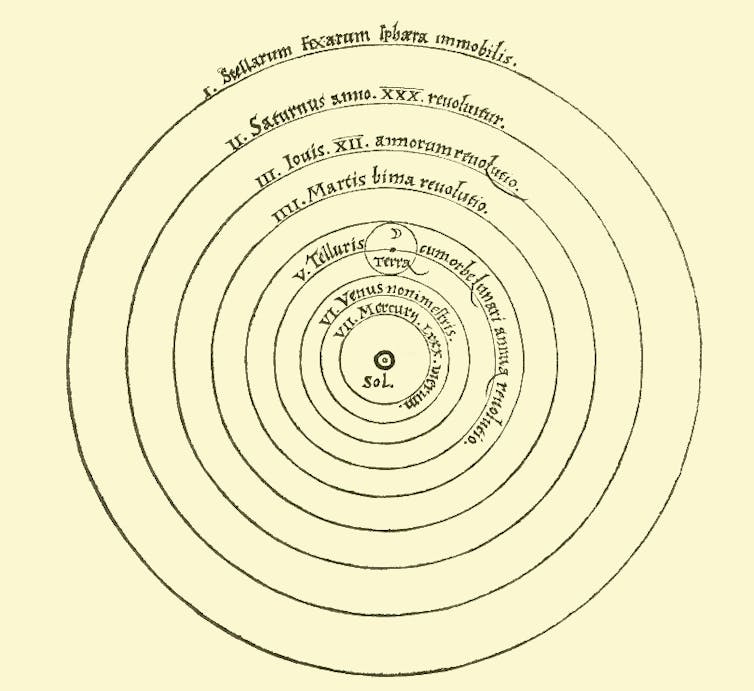

This was the consequence of the transition from a Ptolemaic view, in which Earth was at the centre of the universe and everything revolved around it, to a Copernican view in which the Sun was at the centre and our planet, along with all the others, revolved around it.

It followed that if we were now more like other planets and moons close to us that revolved around the Sun, then they were more like Earth. And if other planets were like Earth, then they most likely also had inhabitants.

Robert Burton’s remarks in his The Anatomy of Melancholy(1621) were common:

If the Earth move, it is a Planet, and shines to them in the Moone, and to the other Planitary inhabitants, as the Moone and they doe to us upon the Earth.

Similarly, the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629–95) believed life on other planets was a consequence of the Sun-centred view of Copernicus. But his speculation on such matters proceeded from the doctrine of the “divine plenitude”. This was the belief that, in his all-powerfulness and goodness, having created matter in all parts of the universe, God would not have missed the opportunity to populate the whole universe with living beings.

In his The Celestial Worlds Discover’d (1698), Huygens suggested that, like us, the inhabitants of other planets would have hands, feet and an upward stance. However, in keeping with the greater size of other planets, particularly Jupiter and Saturn, they might be much larger than us. They would enjoy social lives, live in houses, make music, contemplate the works of God, and so on.

Others were much less confident in speculating on the nature of alien lives. Nevertheless, as Joseph Glanvill, a member of the Royal Society alongside Isaac Newton, suggested in 1676, even though details of life on other planets were unknown, this did not prejudice “the Hypothesis of the Moon’s being habitable; or the supposal of its being actually inhabited”.

God’s work

That other worlds were inhabited also seemed an appropriate conclusion to draw from early modern science focused, as it was, on God’s work in nature.

This was a theme developed at length by the most influential work on the plurality of worlds in the latter part of the 17th century, the Copernican Bernard Fontenelle’s Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes(Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, 1686).

To Fontenelle, there was an infinite number of planets and an infinite number of inhabited worlds. For him, this was the result of the analogy, as a consequence of Copernicanism, between the nature of our Earth and that of other worlds.

But it was also the result of the fecundity of the divine being from whom all things proceed. It is this idea “of the infinite Diversity that Nature ought to use in her Works” which governs his book, he declared.

The seed of Adam

But there was a significant problem. If there were intelligent beings on the Moon or the planets, were they “men”? And, if they were, had they been redeemed by the work of Jesus Christ as people on Earth had been?

John Wilkins (1614–72), one of the founders of the new science, wrestled with the theological implications of the Copernican universe. He was convinced the Moon was inhabited. But he was quite uncertain whether the lunar residents were of “the seed of Adam”.

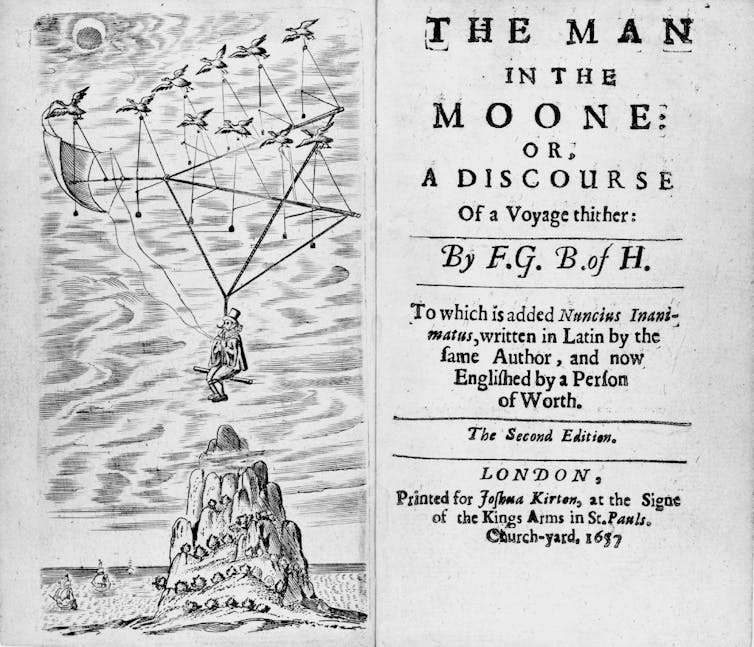

Wilkins’s simple solution was to deny their human status. The inhabitants of the Moon, he suggested in his The Discovery of a World in the Moone (1638), “are not men as wee are, but some other kinde of creatures which beare some proportion and likenesse to our natures”.

In the end, Fontenelle was also to adopt this solution. It would be “a great perplexing point in Theology,” he declared, should the Moon be inhabited by men not descended from Adam. He only wished to argue, he wrote, for inhabitants “which, perhaps, are not Men”.

The existence of aliens – human, just like us – threatened the credibility of the Christian story of the redemption of all humans through the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. This was intellectual space in which only the theologically brave – or foolish – dared to travel.

It was much easier to reject the humanity of the alien. Thus, our modern belief that aliens are not like us originated as the solution to a theological problem. They became “alien”, literally and metaphorically. And, therefore, threatening and to be feared.

A product of the divine?

We no longer live in a universe that is seen as the product of the divine plenitude. Nor one in which our planet can be viewed as the centre of the universe. As a result, ironically, we have become aliens to ourselves: modern “alienation” is that sense of being lost and forsaken in the vast spaces of a godless universe.

In the early modern period, aliens were not looked upon as threatening to us. They were, after all (even if they were not “men”), the product of divine goodness. But, in the modern world, they both personify and externalise the threat to our personal meaning, one that results from our being in a world without ultimate meaning or purpose.

As projections of our own alienation, they terrify us, even as they continue to fascinate us.