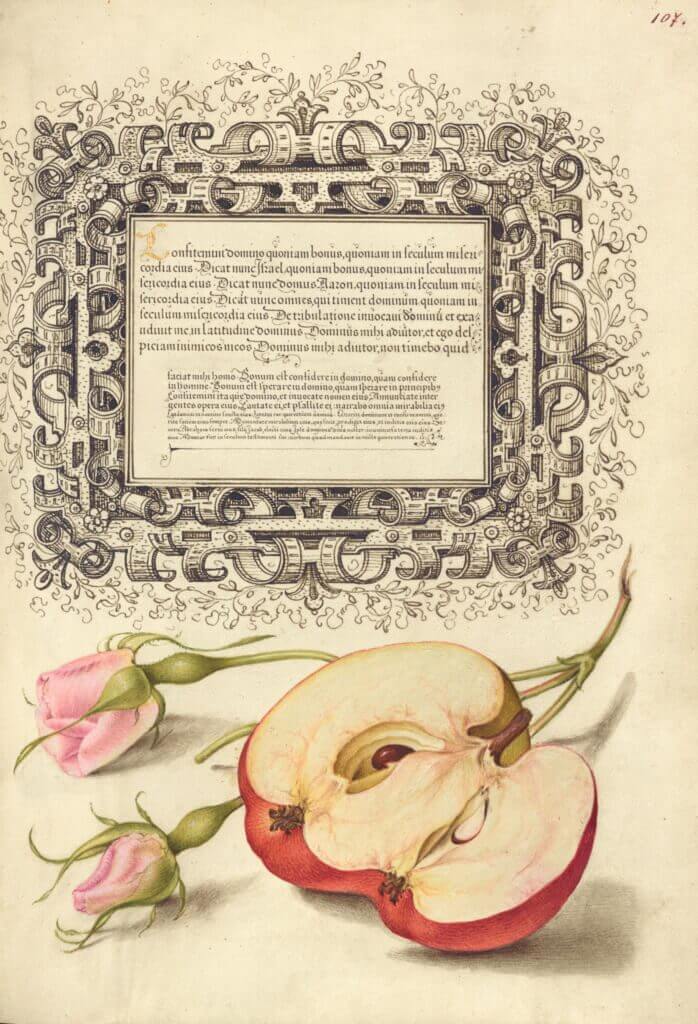

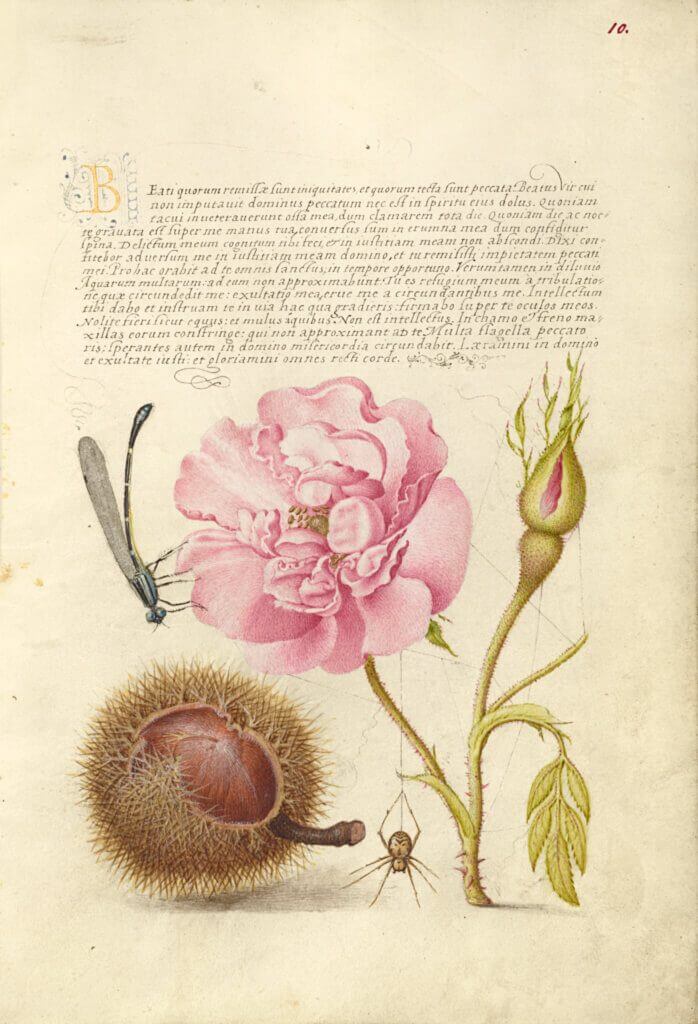

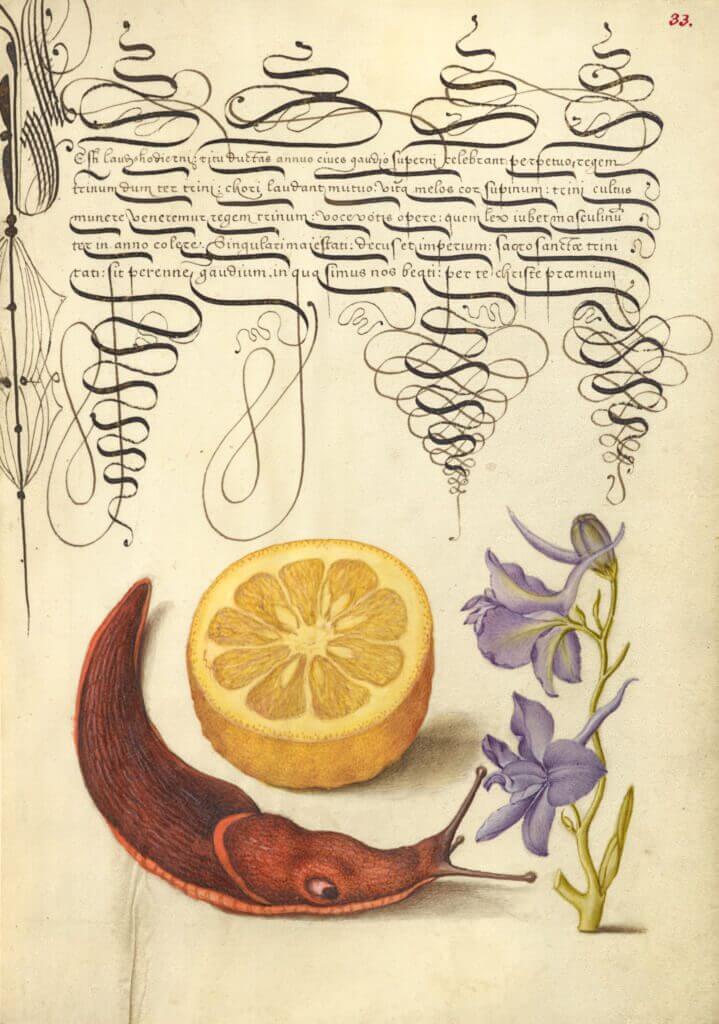

Small enough to hold in the hand, the allure of the Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta (Wondrous Monuments of Calligraphy) in the Getty Museum’s collection of manuscripts is undeniable. Hold the book close enough, and the butterflies seem to quiver before your eyes and the fruit looks good enough to eat.

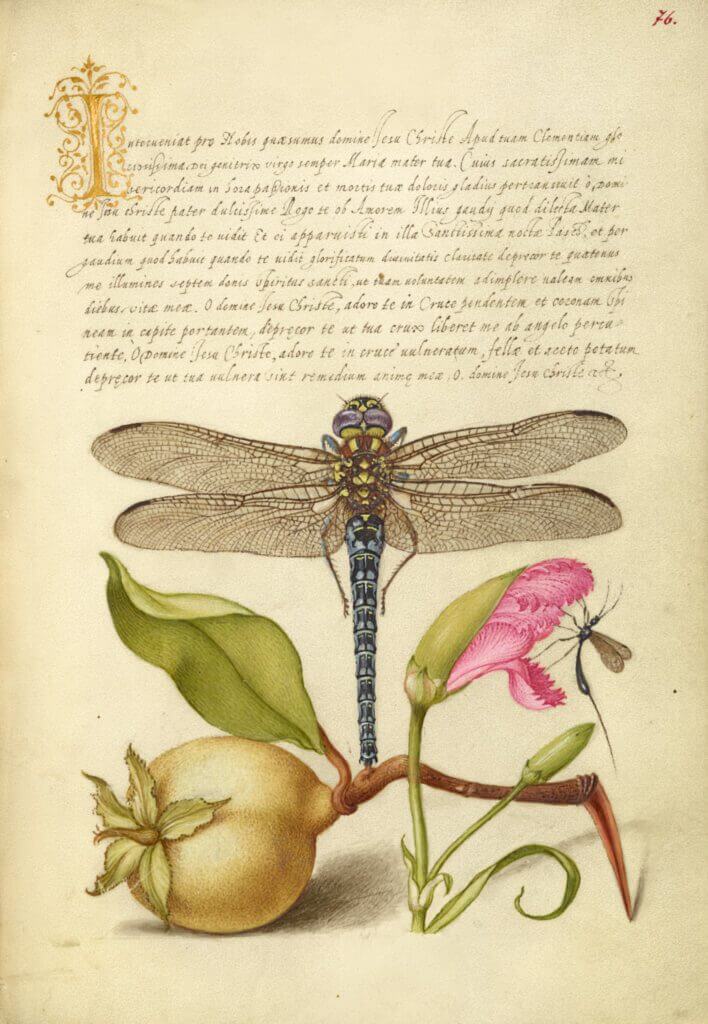

This manuscript contains a collection of models for elaborate and decorative script, written during the 1560s by calligrapher Georg Bocskay. Thirty years later artist Joris Hoefnagel filled the available blank spaces with exquisitely-painted naturalistic depictions of flowers, fruits, seedpods, insects, caterpillars, mollusks, lizards, frogs, mice, and other small creatures. The detail is so fine, his brushstrokes are nearly invisible to the naked eye.

Hoefnagel’s contributions completely transformed the book. His images create a unique experience, placing nature’s cornucopia in the reader’s hand, and inspiring awe and wonder in the late-16th-century viewer.

Fast forward to 2020, and the digital age. Now, new imaging has captured the subtle hues of Hoefnagel’s pigments and colorants, as well as the color and surface texture of the parchment.

Viewable in a newly published facsimile and online, readers can now appreciate the impossibly tiny spiraling micro-writing; observe the subtle differences between the green leaves of the crossed tulips; almost feel the rusting surface of the apple; and be delighted by the hair-fine web spun by the spider. Each page of the new book reflects the quantum leaps in digital technologies since the 1992 publication of Getty’s first facsimile edition.

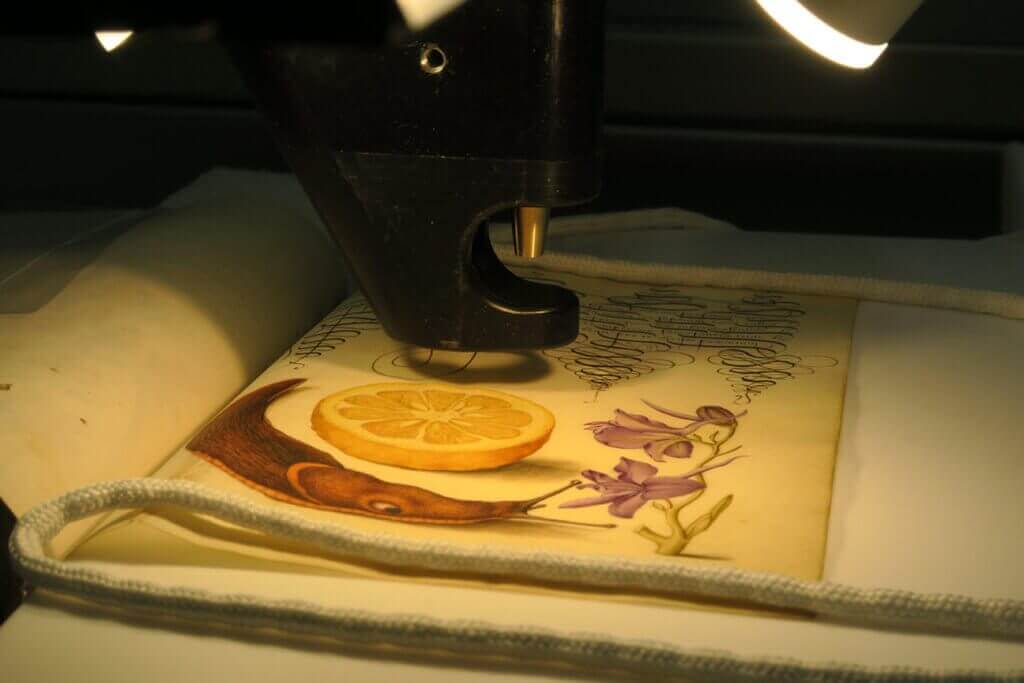

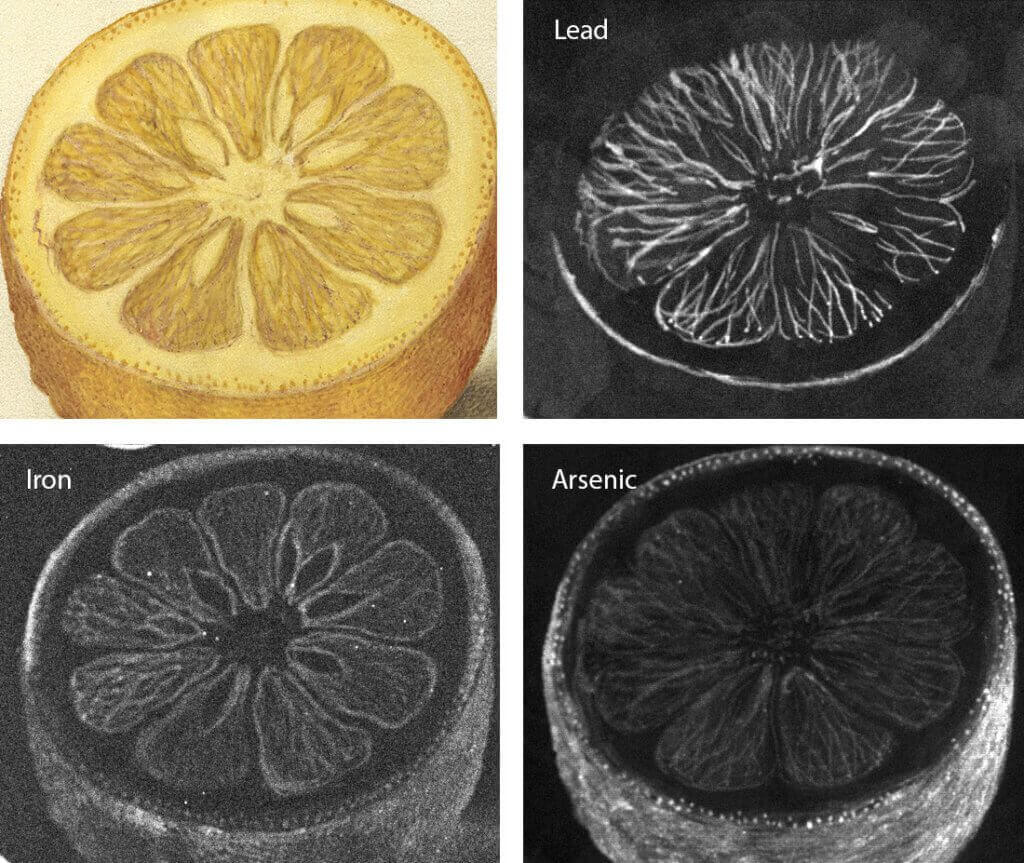

Along with the new images, recent advances in methods of scientific analysis brought to light information about how Hoefnagel painted these astonishingly lifelike depictions. Non-invasive systems that do not touch or remove anything from the surface of the page provided clues to the pigments he used in almost every brushstroke. One of these techniques, macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) scanning, used a narrow beam of X-rays to map the distribution of chemical elements (e.g. lead, iron, copper) across the surface of the page. Knowing these elements made it possible to identify which pigments were used.

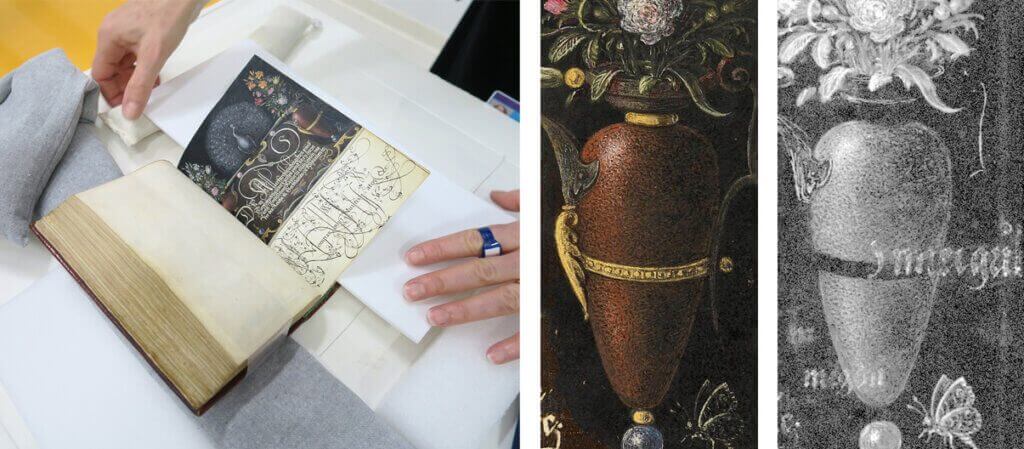

The macro X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer in position to record the distribution of chemical elements across the painted image of the sour orange. Note that the tip of the instrument is several millimeters away from the surface of the page, ensuring that the manuscript is not damaged in any way.

Hoefnagel’s extraordinary illusionistic effects may seem like they’d depend on a whole new range of materials. But his paints were found to be no different than those of generations of manuscript illuminators who came before him. It was how he used them that sets him apart.

Attuned to the slightly different hues, textures, and opacities achievable by his materials, Hoefnagel carefully selected each pigment to achieve the desired effect. For example, the sour orange was painted with several different red and yellow pigments, including orpiment yellow, vermilion red, red lead, and red ochre.

The element maps produced by the macro-XRF scanner shed light on how Hoefnagel mixed and layered his pigments. For this sour orange, the artist combined the mineral pigment orpiment yellow (seen in the arsenic map above) together with red and yellow earth pigments (captured in the map for iron, above) to create the rind. He used lead-containing pigments (either white lead and/or red lead, shown in the map for lead, above) to create the distinctive outlines of the fruit’s individual sections and seeds. Although this imaging technique cannot detect organic pigments, it looks like he used an organic yellow pigment on the white inner rind, to differentiate it from the white of the parchment.

Throughout the book, Hoefnagel selected different red and yellow pigments, exploiting each pigment’s unique quality for a particular purpose. For example, to paint a dragonfly, he used the cool yellow hue of the pigment lead-tin yellow to articulate its sectioned body. He also used an insect-derived lake pigment (possibly cochineal) for the bright magenta leaves of the carnation.

Because it uses X-rays, macro-XRF scanning can also see below the surface of the paint. Surprisingly, on one page, words hidden beneath the flower vase in the page margin at right could be seen in the lead map. What do they say? We don’t know. Yet.

Even if we can’t read it, this discovery may hold a clue to the creative process. Was this text something Bocskay made as a test, that Hoefnagel cleverly hid beneath the vase? With intriguing discoveries like these, entirely new questions emerge. New findings help direct future research. This manuscript will continue to fascinate all those who encounter it—now and into the future—as new technologies become available that will further reveal its wonders.