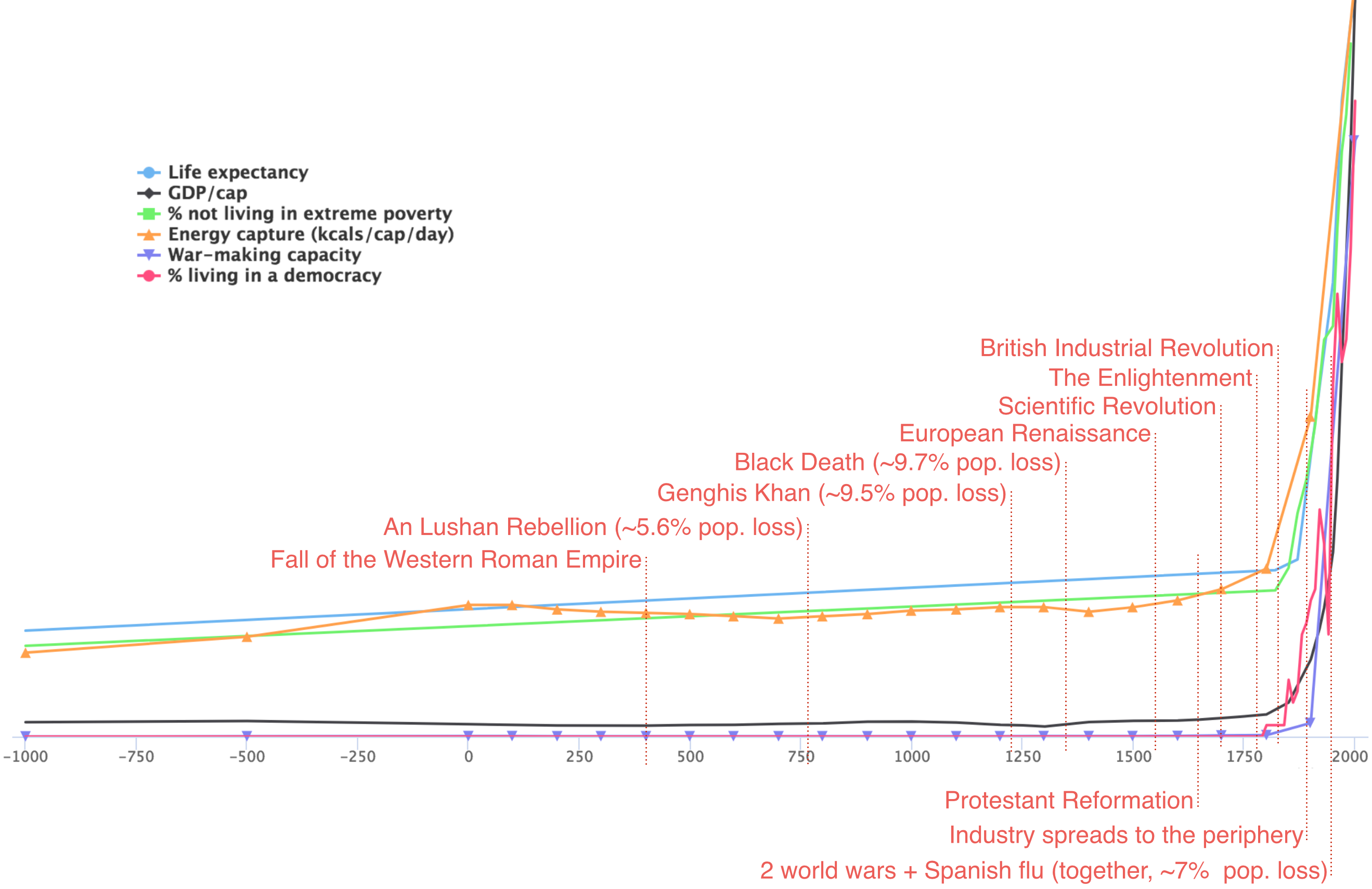

Until the majority of humans fell to the transformative impacts of the Machine Age some hundred or so years ago, when power generation, electricity, the automobile, factories, and telecommunications all conspired to dramatically alter how we lived and interacted, a common set of governing principles underpinned life on Earth for more than ten thousand years.

Unless you were a noble.

Chief among these was the fact that life required immense personal effort. Most of us made our own homes from trees we cut down, and we also made everything in them. We raised animals and planted gardens. We made our own clothing, food, and supplies. We gathered wood with which to heat ourselves, and to cook. We repaired everything that was broken; and made do if we couldn’t. We ebbed and flowed with the rhythm of days and seasons over which we had no control. We lived off the land we tended; fifty to eighty percent of us were farmers, just a century ago. And the entire family — men, women and children — all contributed to the family’s wellbeing.

This is a story about that majority.

Relative to today, life was incredibly tough unless you inherited land, a title and a family fortune, or curried favor with someone who did. It was, very literally, subsistence living. We eked out a life that revolved around an agrarian calendar, trying to grow enough food to survive for another year. But there were overwhelming upsides to enduring these hardships, too. For one, we were self-sufficient. While part of our yield might have gone to pay the lord, daimyo, pomeshchik, junker, or jagir who granted us rights to farm their land, none of us was at the mercy of someone else’s priorities, schedule, value system, or talents.

In addition to being autonomous, we were strong mentally and physically, because life demanded that strength from us, lest it crush us.

At a high level, it is what came afterwards that began the great unravelling of our autonomy, stamina and fortitude.

Our Long, Slow Descent

For all its marvels, the Machine Age ironically brought about the death of practical autonomy. Gone was pervasive self-employment. Gone were the flexible work hours families enjoyed — as tough as life was — insofar as organizing our own time and efforts. Gone, therefore, was our sovereign control over balancing our own priorities. Gone, too, was control over the production of the goods and services we needed to survive, as more and more of it became outsourced to centralized production facilities, and the people who manufactured and sold them. Gone was the time-worn tradition that what we made was (mostly) ours to keep and use or trade. It now belonged to those for whom we now — suddenly — worked and who determined what portion of our own labors were to be meted out. Usually, this amounted to a pittance, deepening our indentured servitude to our new overlords, rather than freeing us.

Gone, too, was our broad skill set — the one that led us to handle all aspects of living. This was replaced by a new idea — that of specialization. Human beings went from being jacks of all trades, to being masters of one, to grease the wheels of increased productivity. That’s because complex, machine-age tools demanded a new class of laborers who could do one thing over and over again, six or seven days a week, efficiently, to optimize output, and hence the economic gain. We left our fields for this, because it helped us overcome nature’s vagaries, and climb out of poverty. But once we decamped en masse to the factories, our autonomy wasn’t the only thing to fall apart. Our nuclear families did, too, as everyone — children included — entered the labor force, for the ostensible benefit of the “new overlords”.

An appraisal of the industrial era family, by the UWGB, includes the following passage:

“It was difficult to spend quality time together because of long workdays, so relationships often became strained. Mothers struggled to keep their families in good health, while also struggling to money. A lot of times, children would have to go to work for factories as well, because they were smaller [than adults] and could fit into smaller spaces. Children earned 1/10 of what men earned in factories. Many young women would work for [them] when they were younger, but once they married, they would quit their jobs to take care of the home. To make ends meet, some women would continue working in the factories or mines while they were pregnant.”

The birth of economics and capitalism were not coincidental with the rise of the machine. They went hand in hand, because one fueled the other. As fewer and fewer people farmed, moving to urban centers to participate in industrial life, more and more production was outsourced to specialists. Beyond the production of goods, a new constellation of services emerged, in this period, further diminishing our autonomy, as we entered complex relationships with countless people who now made or sold what we needed, or who helped us navigate a suddenly complex world, in stark contrast to our erstwhile self-sufficiency. There were shop keepers, bank tellers, merchants, insurance agents, accountants, managers, doctors, lawyers, entertainers, advisors, advertisers, writers, and teachers. And within each group, there were sub-specialists to decode and administer to ever-increasing complexity.

What we now call “the middle class” developed from this enterprise. With a first-time-in-human-history surge in human productivity — a metric that had remained totally flat for thousands of years — fed by powerful machines and the outsourcing of food production that had dominated our lives — new hierarchies appeared daily, and with them, a sliding scale of economic clout.

Thus, the chief focus in life shifted from subsistence to wealth accumulation. To be cheeky, “enough was no longer enough.” And so, the outsourcing of most of our needs, and a new category of desires that economics made possible, hammered the final nails into the coffin of our self-sufficiency, and for the working class specifically, our self-determination, too.

Once these things set in, our long, slow decline began. Today, nearly every person in a developed, Level 4 nation would be incapable of surviving without the trappings of modern life. In my view, this makes #winning more than a little bit #bullsh*t.

The greatest casualty of the Industrialization of the world was our near-total disempowerment. Yes, far fewer children die. Yes, most of us earn a lot more money. Yes, we now have leisure time, and cash for frivolities. Yes, scientific discoveries have improved nearly every aspect of life over pre-industrial times. But while most of us can now choose a career, a spouse, a getaway and non-essential trinkets, there is a downside to this, too.

That’s because the moment life ceased being the product of largely autonomous acts, as we increasingly depended on strangers to both employ us and produce the goods we needed, we became ignorant and soft — physically, mentally, and interpersonally.

Over time, this has snowballed.

A Timeline of Loss

First, we lost our broad skill sets, and with them our security in being able to control the outcomes of our own wellbeing.

Quickly afterwards, we lost our capacity to endure hardship, as a result of which our expenditure of effort has ultimately withered.

Before long, we lost our civility toward one another, because we were now transacting strangers, rather than members of a tight-knit clan, or community. Our manners have mostly followed civility into the toilet.

Eventually, we lost our integrity — our moral principles, and uprightness. In a world of dog-eat-dog competition, integrity is seen as a distraction, or “bad business”. Once that was mostly gone, so, too, was our trust. In business, we stopped being open and honest with one another a long time ago.

As we prayed to our new “golden calves” — the capitalist gods, we lost our interest — in the world, in our own history, in one another, in differences… and in learning itself. We became utterly self-absorbed, in the act of accumulating wealth. Fast forward to 2020. We no longer have anything interesting to say to one another — nor interest in one another, really — so we focus instead on taking pictures of ourselves, out of self-obsessive boredom. We have all become Narcissus, enamored with our own reflection.

In a recent study, Microsoft found that the average adult cannot focus for more 8 seconds, a number that is dropping precipitously. In a separate and equally troubling metric, Google reports that on the Android platform alone, we take nearly 100 million selfies, per day.

Because what else is there to do?

With such ennui setting in on Project Human, our loss of tolerance for any form of discomfort was a foregone conclusion; because unlike the other things that bored us, we couldn’t simply “flick” discomfort away. Today, emotionally, the smallest quibble or even word can raise our furor; while coarse textures, non-stretchy clothing and shirt labels have become too much to bear. Worst of all, any delay in gratification drives us to bitter complaint, and rigid intolerance.

Peasants around the world are rolling in their graves.

The street pajamas that suddenly proliferate everywhere — Lululemon, Champion, Athleta, Adidas, Under Armour, Sweaty Betty, Fabletics and my favorite for its bluntness: Beyond Yoga (cuz let’s face it — you’re not actually exercising in this stuff) — are all the proof you need of a species that wants nothing more than to curl up in bed with our “activewear” and social media, and be left alone until it’s time to answer the door for our UberEats.

Finally, out of all of this — the loss of fortitude, effort, civility, manners, integrity, knowledge, trust, interest, personal investment and tolerance, not to mention the meteoric rise in street pajamas and selfies — came the crippling blow: the loss of hope.

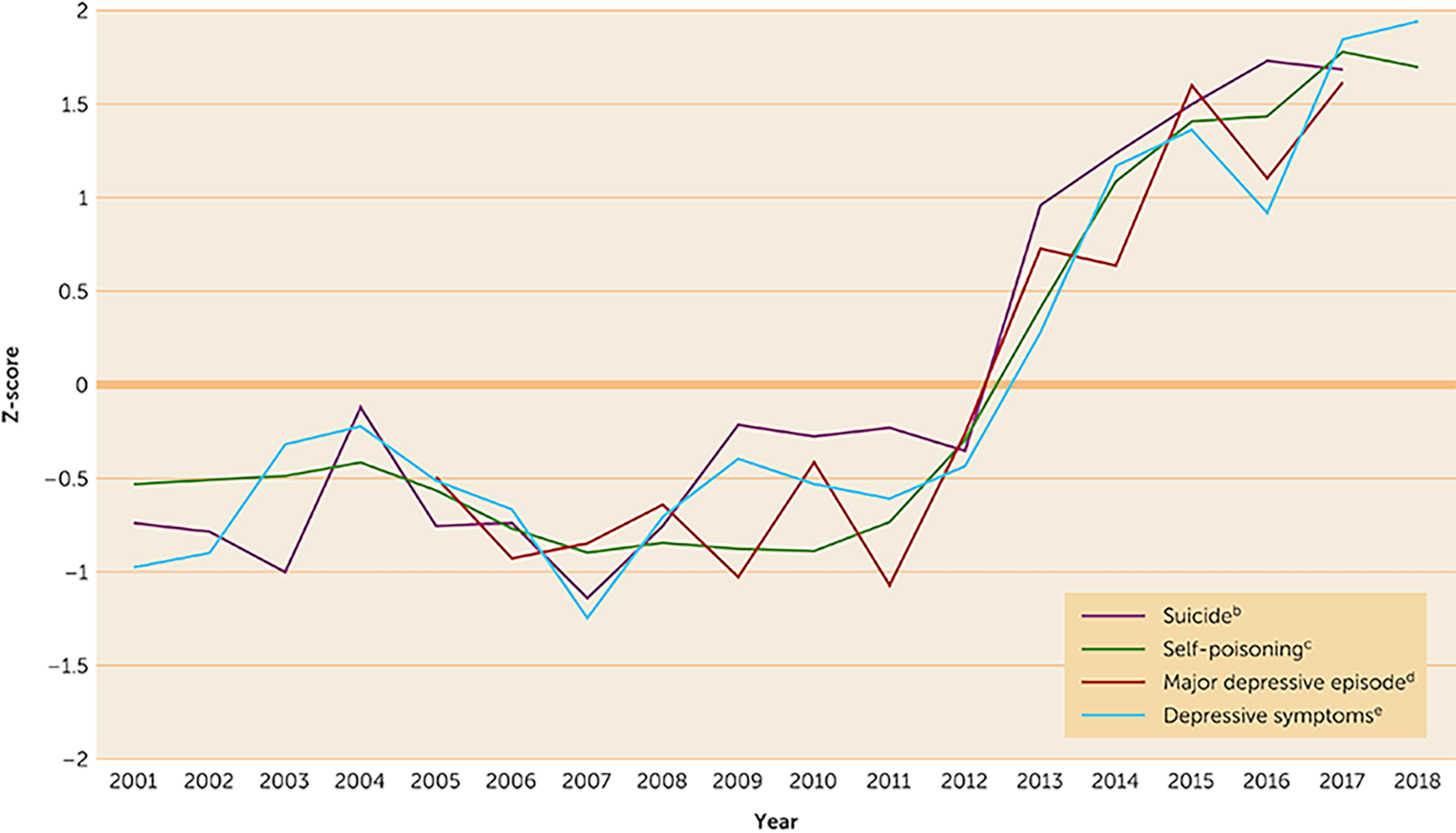

In a decade alone, suicide rates in the U.S. have risen by 60%. Worse, still, 60% of all young adults in America are reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression.

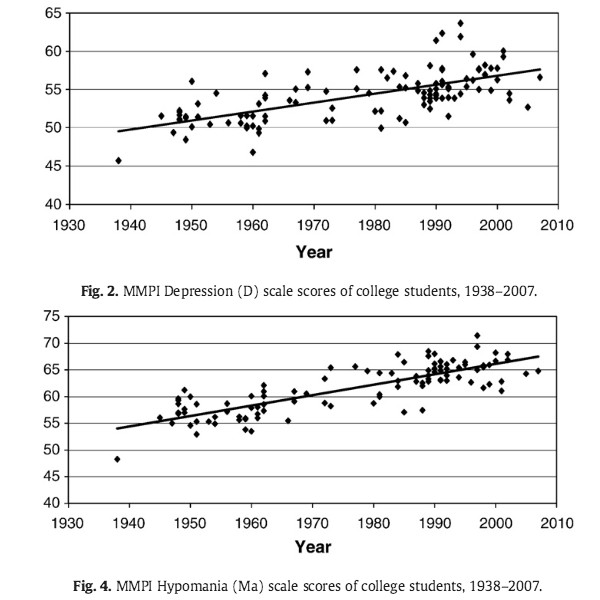

Dr. Jean Twenge, a social psychologist at San Diego State University and the author of Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled — and More Miserable Than Ever Before — is one of the leading researchers into long-term trends. She has charted mental health rates dating from the 1930’s, through today. Her conclusions?

Twenge attributes this worsening to modern life.

“Obviously there’s a lot of good things about societal and technological progress, and in a lot of ways our lives are much easier than, say, our grandparents’ or great-grandparents’ lives. But there’s a paradox here that we seem to have so much ease and relative economic prosperity compared to previous centuries, yet there’s this dissatisfaction, there’s this unhappiness, there are these mental health issues in terms of depression and anxiety.

“Modern life doesn’t give us as many opportunities to spend time with people and connect with them, at least in person, compared to, say, 80 years ago or 100 years ago. Families are smaller, the divorce rate is higher, people get married much later in life.”

While Twenge is no apologist for days when racism and sexism were more openly rampant than they are today, she urges us to be “clear-eyed that the potential tradeoff for our equality and freedom is more anxiety and depression because we’re more isolated.”

It’s ironic in the age of isolation to be simultaneously less autonomous.

Life on Earth today — when seen from a distance — looks a lot like a swarm of animals scavenging for scraps in man-made piles they no longer understand, from which piles we wander aimlessly, looking for meaning and focus in the absence of clarity, overwhelmed by the dizzying complexity and abstraction of a life largely removed from the simple life our forebears knew: the nuclear bonds of a strong family; the connection to a community, and to a planet that we fed from, regularly; the fortitude of persevering — together — to make a life; the acceptance that the Earth was our landlord, and that we dwelled in duration and quality at her sole discretion; and that the investment of our wholesale energies in honing our minds and bodies to better cope with all of it, was the best investment we could make, and the one that defined our lives.

Whoever you are in the post-modern world, the loss of hope is your common denominator.

A Bit of History

Back in July, I wrote a piece on civility, after my daughter and I were plowed into by a woman as she exited a store while I held the door open for her, without a thank you, a smile or an acknowledgement, apart from being bulldozed. Without even feigning kindness, I turned and told my daughter, “Civility is on its deathbed.” I meant it, but it’s far worse than that. Civility began to wither the moment classes and hierarchies arose in the West. Before the Industrial Revolution, there were only two classes: Nobility and Peasants. The 80% of us who were peasant-farmers — the fuel of the so-called “cottage industry” that proliferated — were the people I described in the preceding paragraphs. With the birth of machines, however, came an avalanche of employment: the laborers, managers of people and product, salesmen, executives, owners, and every type of specialist imaginable in the constellation of doing large-scale, complicated, multi-human work. This phenomenon created, and increasingly exacerbated, the disparity of means and access, which in turn conspired to make some humans think themselves superior to others, then behave accordingly to this myth.

Before the Machine Age, only the nobility were prats and wankers, to borrow two terms from the place where the revolution began: jolly old England.

Suddenly, everyone was.

And so, the great manners of the gentry in the Age of Enlightenment, and the inherent modesty of peasants, gave way to a world where everyone was now a miscreant or reprobate.

Or, in today’s parlance, an arsehole.

The nobles’ and knights’ world of chivalry withered away quickly. Irish statesman Edmund Burke wrote in 1790, as the Industrial Age got underway, that, “The age of chivalry is gone: that of sophisters, economists and calculators has succeeded: and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever.” Some decades later, Charles Dickens, the famed English writer and social critic, bemoaned, “The age of chivalry is past. Bores have succeeded to dragons.”

Fast forward 200 years to rapper will.i.am, who says, “There’s no chivalry in culture any more. Sometimes you meet someone who everyone says is polite and you’re like, ‘Wow,’ but then it’s like, ‘Hang on, isn’t everyone supposed to be polite?’”

Sadly, we are, but it ain’t happenin’. We used to open doors for one another. Now we push each other out of the way in our rush. We used to look one another in the eye in conversation. Now we scarcely look up from our screens to acknowledge one another’s presence. We used to exhibit patience toward people and processes. Now we malign the fact that they require effort or time we are no longer willing to muster, unless we can cash in on the efforts. We used to listen. Now we just talk. We used to stretch our minds to help our families. Now we stretch our bodies instead, off of which doctors, insurance agents and food engineers make a fortune. And we used to dress as though we cared — an effort that reflected our investment in ourselves, and in one another. Now we shuffle down streets in our bedwear, a corollary to the amount of thought we put into our social lives.

Which is approaching zero.

The Economic Dagger

But autonomy. I mean, we have choice now, right? And everyone’s on the winning side of economic gain, which leads to more autonomy, right?

I’ve said again and again that capitalism has ironically led to the death of autonomy, not its expansion. What has occurred instead is a wild bifurcation between a 90-plus percent majority who find themselves struggling to make ends meet, and a “new aristocracy” who now live strikingly similar lives to their pre-Industrial patrician forebears. If you’re not one of them, life has become increasingly difficult, as prices of everything skyrocket, leaving more and more people on the losing side of fate.

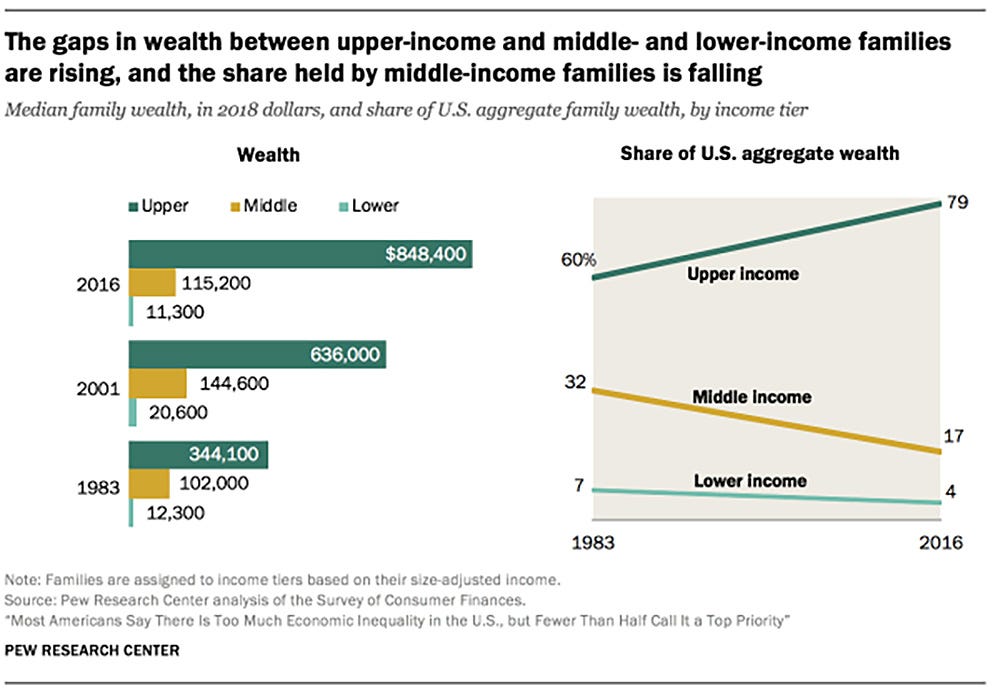

In fact, 73% of Americans, to pick on them, die in debt, according to credit bureau Experian — some $62,000 of it, on average. It’s not surprising. The Pew Research Center reports that in just the past 33 years alone, the American wealth gap has become an abyss. Lower and Middle income families have lost half of their wealth — wealth that has gone straight into the pockets of the upper class, who now controls 79% of all U.S. wealth.

Then, there’s college. While the institution didn’t even exist in pre-Industrial times, today, a college degree is still the church key out of poverty, or into opportunity of any kind. Today, as CNN Money reports, even those making three times the national median U.S. income — $100,000/per year — cannot afford 60% of the universities in the nation. In fact, The Atlantic answered its own question about why college is so expensive in the U.S. Americans, it says, spend more on college and ancillaries — housing, books, meals — than any other country in the world: $30,000 per year, on average: the median salary, before tax. Even the 75% of American students who attend the lowest-cost state-run colleges cannot afford the tuition anymore. Why, you ask? Because of the love affair that American Republicans have had with small government for more than a half-century, school funding has been slashed year over year, pushing the onus onto families to pony up, or wither.

Whither goes the cost of college, so goes the accumulation of debt.

And yet: a college degree is still the fastest path to a better life. Forbesreports that the earnings for someone with a bachelor’s degree are nearly twice that of someone without one. Moreover, unemployment among the same group is nearly half that of workers with a high school diploma. So the yawning economic gap begins to make sense. The rich get richer, while the poor get poorer, as the aphorism goes.

Then, there’s the nature of those jobs. As Americans do less and less manufacturing, and more and more service industry or professional jobs, more people are being left out in the cold. Before 1980, two thirds of jobsrequired just a high school diploma or less. Today, 70% of them require some college education.

But even those who can afford it do so with an albatross around their necks. 62% of graduating students do so in debt.

All of this — adults and children in debt, and a growing economic divide between the new aristocracy and the also-rans — conspire to drive us to a quality of life that looks eerily similar to the one most of us had before the Industrial Revolution took us out of our homes and into the factories. The difference, distressingly, is that “back then” we had dominion and agency over our own lives. We produced everything we needed, and our nuclear families were strong. We worked for no one, and we had grit and fortitude.

Now, we aren’t even educated anymore, and all those high-paying jobs are going to citizens of countries who don’t suffer from Americans’ specific brand of greed.

Yet.

Americans are not only losing their fortitude, effort, civility, manners, integrity, knowledge, trustworthiness, interest, the investment of time, and tolerance. They are also now losing their minds, quite literally, which is why we are seeing such a vertiginous rise in not only despair, but bigotry, as well as ever-more outlandish conspiracy theories — idiotic beliefs in stolen elections, Jewish space lasers, child-eating pizza peddlers, mind-controlling vaccines, and coronavirus-spreading 5G broadband, to name just a few of the “fun” ones.

In short, it’s hard not to believe crazy things when our minds are made of mush.

Final Thoughts

First, the shift to Industrial Age life robbed us of our fortitude and our autonomy, as new overlords began to see us as tools for wealth creation, rather than neighbors and friends with agency. Pretty soon, we began to see life that way ourselves, because it was “sink or swim”. The genie couldn’t be put back in the bottle.

Once we began vying against one another for scraps, we chose paths to wealth creation, and in the process, we lost context, and skills. This further weakened us, making us ever more dependent on others to do what we no longer could: feed and clothe ourselves.

As life became more complex, we understood less and less of it. Civility, manners, knowledge and interest all plummeted as we focused on making our way through specialization, because that’s what the age demanded. Frankly, it does, still. And the specialist is the enemy of the polymath, even though polymaths invented the world. If you want to go down thatparticular rabbit hole, I wrote this piece.

Because we cannot go backward, we need to chart a path forward, toward recapturing some of the agency we used to have in our lives, within the context of a highly strained present. In my view, that path is through a return to polymathy, and the recalibration of self.

Polymathy requires the investment of our time and energies to expand our contextual understanding of the world. It is the currency of innovation, having led to most of the most transformative inventions of all time, from the column (Imhotep) to the printing press (Gutenberg) to water purification (Amy) to electricity (Franklin), to the theory of evolution (Darwin) and wireless transmission (Tesla), among a thousand other things. It is also the path to autonomy within the current world of capitalistic fervor. In fact, the creators of the world’s 5 most valuable companies — hence its wealthiest people — are all polymaths: Musk; Gates; Buffett; Page; and Jobs — RIP.

In a very real way, polymaths are not unlike pre-Industrial farmers: jacks of all trades, with broad skill sets in a variety of endeavors, leading to increased resilience.

Hmmm.

How does one become a polymath? Read the article I tagged 2 paragraphs up. But know this: polymathy is a fancy term for someone with broad (aka multiple) skill sets, pursued to a level of fluency — of expertise. Once you know what one is and what they’ve done for us, a better question is, whybecome a polymath? An Observer article I read provides a great set of incentives, that I simplified into this list:

- The combination of skill sets can lead to new discoveries

- Most creative breakthroughs come from atypical combinations of things we’ve learned

- It’s faster than ever to become proficient in a new skill

- The explosion of data leads to fertile ground for innovation

- Polymathy future-proofs your career

- It builds capacity for navigating increasing complexity

- Polymathic thinking and acts make you anti-fragile

I don’t know about you, but I like anti-fragility, especially in an increasingly competitive, unaffordable, confusing, depressing, and volatile era.

To become anti-fragile, we have to rediscover our inner agency, and self-determination. And the best path I know of doing that — of future-proofing life, in spite of its increasing unaffordability, and the inexplicable street pajama and selfie scourges — is the investment of time into one’s broad and deep — aka T-shaped — education.

So, consider this a public service announcement for polymathy. Or, an apology for the weak species we’ve otherwise become — new aristocracy included.

Just don’t tell them. They’re too busy #killingit.