Key Takeaway:

Neanderthals lived in small, close-knit groups that were highly nomadic. Their behaviour varied culturally from group to group and over time. As early as 250,000 years ago, Neanderthals were mixing minerals such as manganese with fluids to make red and black paints. At least 65,000 years ago, Neanderthals used red pigments to paint marks on the walls of deep caves in Spain. Colours and ornaments conveyed messages about strength and power. They may have helped individuals convince their contemporaries of their strength and suitability to lead. Neanderthals were producing non-figurative art tens of millennia before the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe. But it is not known whether they produced figurative art such as paintings of people or animals. Neanderthals used visual culture in a different way to their successors.

One of the most hotly debated questions in the history of Neanderthal research has been whether they created art. In the past few years, the consensus has become that they did, sometimes. But, like their relations at either end of the hominoid evolutionary tree, chimpanzees and Homo sapiens, Neanderthals’ behaviour varied culturally from group to group and over time.

Their art was perhaps more abstract than the stereotypical figure and animal cave paintings Homo Sapiens made after the Neanderthals disappeared about 30,000 years ago. But archaeologists are beginning to appreciate how creative Neanderthal art was in its own right.

Homo sapiens are thought to have evolved in Africa from at least 315,000 years ago. Neanderthal populations in Europe have been traced back at least 400,000 years.

As early as 250,000 years ago, Neanderthals were mixing minerals such as haematite (ochre) and manganese with fluids to make red and black paints – presumably to decorate the body and clothing.

It’s human nature

Research by Palaeolithic archaeologists in the 1990s radically changed the common view of Neanderthals as dullards. We now know that, far from trying to keep up with the Homo sapiens, they had a nuanced behavioural evolution of their own. Their large brains earned their evolutionary keep.

We know from finding remains in underground caves, including footprints and evidence of tool use and pigments in places where neanderthals had no obvious reason to be that they appear to have been inquisitive about their world.

Why were they straying from the world of light into the dangerous depths where there was no food or drinkable water? We can’t say for sure, but as this sometimes involved creating art on cave walls it was probably meaningful in some way rather than just exploration.

Neanderthals lived in small, close-knit groups that were highly nomadic. When they travelled, they carried embers with them to light small fires at the rock shelters and river banks where they camped. They used tools to whittle their spears and butcher carcasses. We should think of them as family groups, held together by constant negotiations and competition between people. Although organised into small groups it was really a world of individuals.

The evolution of Neanderthals’ visual culture over time suggests their social structures were changing. They increasingly used pigments and ornaments to decorate their bodies. As I elaborate in my book, Homo Sapiens Rediscovered, Neanderthals adorned their bodies perhaps as competition for group leadership became more sophisticated. Colours and ornaments conveyed messages about strength and power, helping individuals convince their contemporaries of their strength and suitability to lead.

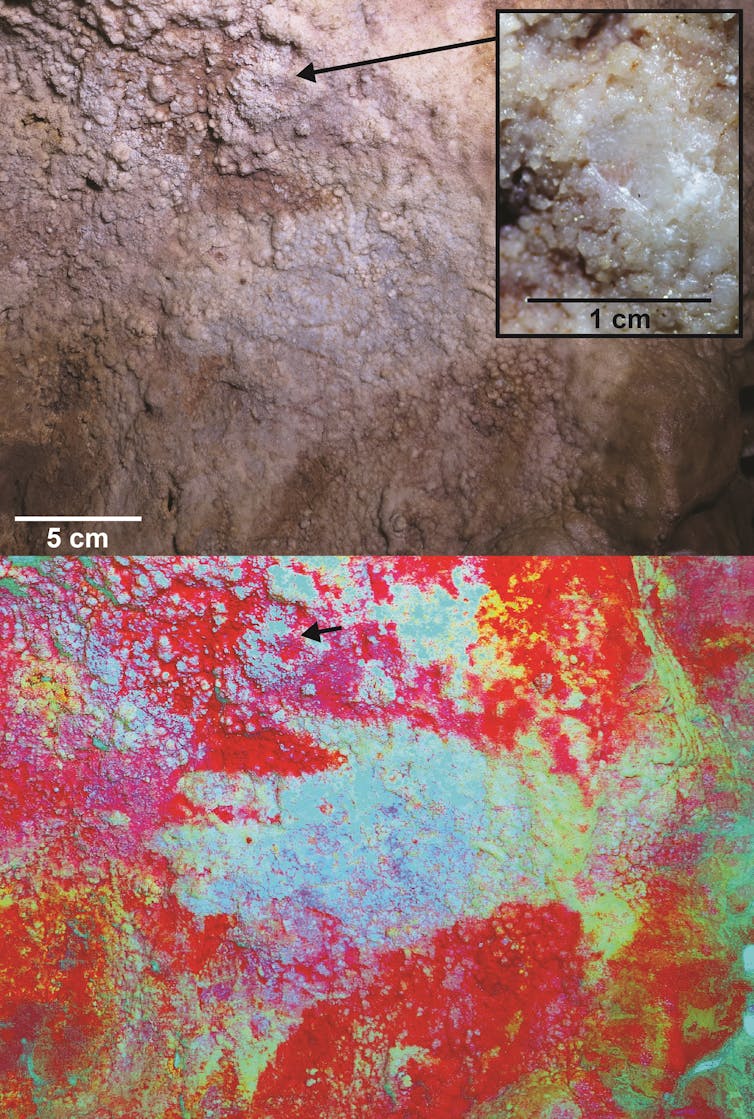

Then, at least 65,000 years ago, Neanderthals used red pigments to paint marks on the walls of deep caves in Spain. In Ardales cave near to Malaga in southern Spain they coloured the concave sections of bright white stalactites.

In Maltravieso cave in Extremadura, western Spain, they drew around their hands. And in La Pasiega cave in Cantabria in the north, one Neanderthal made a rectangle by pressing pigment-covered fingertips repeatedly to the wall.

We can’t guess the specific meaning of these marks, but they suggest that Neanderthal people were becoming more imaginative.

Later still, about 50,000 years ago, came personal ornaments to accessorise the body. These were restricted to animal body parts – pendants made of carnivore teeth, shells and bits of bone. These necklaces were similar to those worn around the same time by Homo sapiens, probably reflecting a simple shared communication that each group could understand.

Did Neanderthal visual culture differ from that of Homo sapiens? I think it probably did, although not in sophistication. They were producing non-figurative art tens of millennia before the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe, showing that they had independently created it.

But it differed. We have as yet no evidence that Neanderthals produced figurative art such as paintings of people or animals, which from at least 37,000 years ago was widely produced by the Homo sapiens groups that would eventually replace them in Eurasia.

Figurative art is not a badge of modernity, nor the lack of it an indication of primitiveness. Neanderthals used visual culture in a different way to their successors. Their colours and ornaments strengthened messages about each other through their own bodies rather than depictions of things.

It may be significant that our own species didn’t produce images of animals or anything else until after the Neanderthals, Denisovans and other human groups had become extinct. Nobody had use for it in the biologically mixed Eurasia of 300,000 to 40,000 years ago.

But in Africa a variation on this theme was emerging. Our early ancestors were using their own pigments and non-figurative marks to begin referring to shared emblems of social groups such as repeated clusters of lines – specific patterns.

Their art appears to have been less about individuals and more about communities, using shared signs such as those engraved onto lumps of ochre in Blombos cave in South Africa, like tribal designs. Ethnicities were emerging, and groups – held together by social rules and conventions – would be the inheritors of Eurasia.