Key Takeaways:

- The world is a networked place, literally and figuratively.

- For example, the network consisting of the international financial corruption scheme uncovered by the Panama Papers investigation has an unusual lack of connections among its parts.

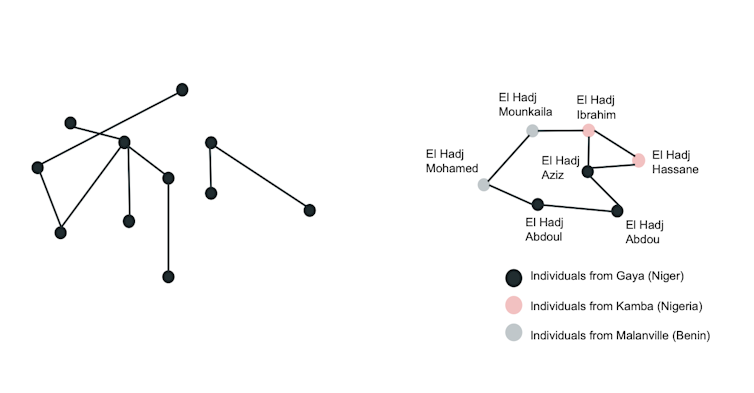

- The concept is so simple that it can be drawn on paper: Entities of interest – people, businesses, countries – are nodes represented as points, and relationships between pairs of nodes are links represented as lines drawn between the points.

- Along with studying emergent properties like the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, researchers have also used network science to focus on problems such as community detection.

The world is a networked place, literally and figuratively. The field of network science is used today to understand phenomena as diverse as the spread of misinformation, West African tradeand protein-protein interactions in cells.

Network science has uncovered several universal properties of complex social networks, which in turn has made it possible to learn details of particular networks. For example, the network consisting of the international financial corruption scheme uncovered by the Panama Papers investigation has an unusual lack of connections among its parts.

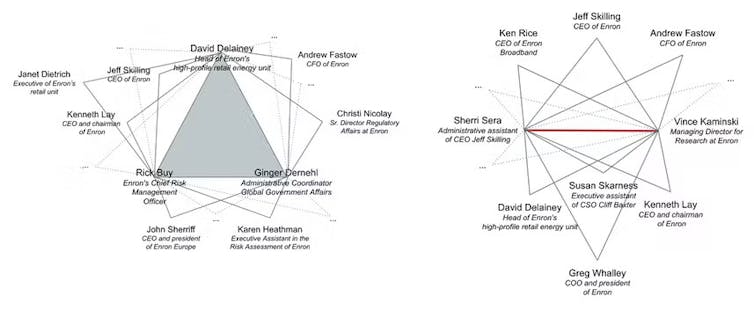

But understanding the hidden structures of key elements of social networks, such as subgroups, has remained elusive. My colleagues and I have found two complex patterns in these networks that can help researchers better understand the hierarchies and dynamics of these elements. We found a way to detect powerful “inner circles” in large organizations simply by studying networks that map emails being sent among employees.

We demonstrated the utility of our methods by applying them to the famous Enron network. Enron was an energy trading company that perpetrated fraud on a massive scale. Our studyfurther showed that the method can potentially be used to detect people who wield enormous soft power in an organization regardless of their official title or position. This could be useful for historical, sociological and economic research, as well as government, legal and media investigations.

From pencil and paper to artificial intelligence

Sociologists have been constructing and studying smaller social networks in careful field experiments for at least 80 years, well before the advent of the internet and online social networks. The concept is so simple that it can be drawn on paper: Entities of interest – people, businesses, countries – are nodes represented as points, and relationships between pairs of nodes are links represented as lines drawn between the points.

Using network science to study human societies and other complex systems took on new meaning in the late 1990s when researchers discovered some universal properties of networks. Some of these universal properties have since entered mainstream pop culture. One concept is the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, based on the famous empirical finding that any two people on Earth are six or fewer links apart. Similarly, versions of statements such as “the rich get richer” and “winner takes all” have also been replicated in some networks.

These global properties, meaning ones applying to the entire network, seemingly emerge from the myopic and local actions of independent nodes. When I connect with someone on LinkedIn, I am certainly not thinking of the global consequences of my connection on the LinkedIn network. Yet my actions, along with those of many others, eventually lead to predictable, rather than random, outcomes about how the network will evolve.

My colleagues and I have used network science to study human trafficking in the U.K., the structure of noise in artificial intelligence systems’ outputs, and financial corruption in the Panama Papers.

Groups have their own structure

Along with studying emergent properties like the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, researchers have also used network science to focus on problems such as community detection. Stated simply, can a set of rules, otherwise known as an algorithm, automatically discover groups or communities within a collection of people?

Today there are hundreds, if not thousands, of community detection algorithms, some relying on advanced AI methods. They are used for many purposes, including finding communities of interest and uncovering malicious groups on social media. Such algorithms encode intuitive assumptions, such as the expectation that nodes belonging to the same group are more densely connected to one another than nodes belonging to different groups.

Although an exciting line of work, community detection does not study the internal structure of communities. Should communities be thought of only as collections of nodes in networks? And what about communities that are small but particularly influential, such as inner circles and in-crowds?

Two hypothetical structures for influential groups

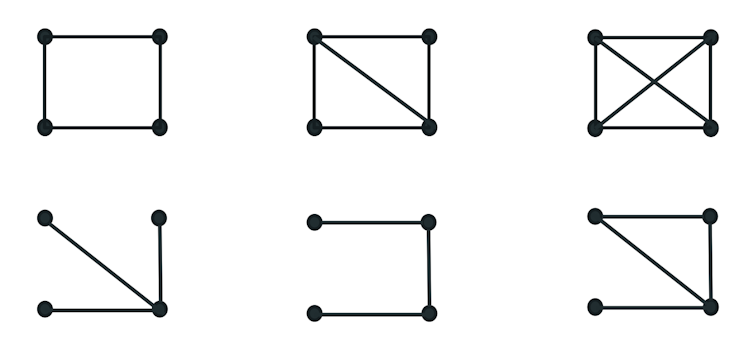

In a manner of speaking, you likely already have some inkling of the structure of very small groups in social networks. The truth of the adage that “a friend of my friend is also my friend” can be tested statistically in friendship networks by counting the number of triangles in the network and determining whether this number is higher than chance alone could explain. And indeed, many social network studies have been used to verify the claim.

Unfortunately, the concept starts breaking down when extended to groups with more than three members. Although motifs have been well studied in both algorithmic computer science and biology, they have not been reliably linked to influential groups in real communication networks.

Building on this tradition, my doctoral student Ke Shen and I found and presented two structures that seem elaborate but turn out to be quite common in real networks.

The first structure extends the triangle, not by adding more nodes, but by directly adding triangles. Specifically, there is a central triangle that is flanked by other peripheral triangles. Importantly, the third person in any peripheral triangle must not be linked to the third person on the central triangle, thereby excluding them from the true inner circle of influence.

The second structure is similar but assumes that there is no central triangle, and the inner circle is just a pair of nodes. A real-life example might be two co-founders of a startup like Sergey Brin and Larry Page of Google, or a power couple with joint interests, common in global politics, like Bill and Hillary Clinton.

Understanding influential groups in an infamous network

We tested our hypothesis on the Enron email network, which is well studied in network science, with nodes representing email addresses and links representing communication among those addresses. Despite being elaborate, not only were our proposed structures present in the network in greater numbers than chance alone would predict, but a qualitative analysis showed that there is merit to the claim that they represent influential groups.

The main characters in the Enron saga are well documented by now. Intriguingly, some of these characters do not seem to have had much official influence but may have wielded significant soft power. An example is Sherri Reinartz-Sera, who was the longtime administrative assistant of Jeffrey K. Skilling, the former chief executive of Enron. Unlike Skilling, Sera was only mentioned in a New York Times article following investigative reporting that took place during the course of the scandal. However, our algorithm discovered an influential group with Sera occupying a central position.

Dissecting power dynamics

Society has intricate structures at the levels of individuals, friendships and communities. In-crowds are not just ragtag groups of characters talking to one another, or a single ringleader calling all the shots. Many in-crowds, or influential groups, have a sophisticated structure.

While much still remains to be discovered about such groups and their influence, network science can help uncover their complexity.