Key Takeaway:

Researchers have discovered that déjà vu is a window into our memory system, alerting us to strangeness when the brain detects familiarity de-synchronizes with reality. Jamais vu, the opposite of déjà vu, occurs when something familiar feels unreal or novel. The researchers conducted experiments on jamais vu, where participants repeatedly wrote the same word, ranging from commonplace to less common. The most common reason for stopping was feeling strange, with 70% stopping after 33 repetitions. The researchers’ unique contribution is the idea that transformations and losses of meaning in repetition are accompanied by a feeling called jamais vu. Jamais vu helps us “snap out” of our current processing, and the feeling of unreality is actually a reality check. The main scientific account of jamais vu is “satiation,” which involves overloading a representation until it becomes nonsensical.

Repetition has a strange relationship with the mind. Take the experience of déjà vu, when we wrongly believe have experienced a novel situation in the past – leaving you with an spooky sense of pastness. But we have discovered that déjà vu is actually a window into the workings of our memory system.

Our research found that the phenomenon arises when the part of the brain which detects familiarity de-synchronises with reality. Déjà vu is the signal which alerts you to this weirdness: it is a type of “fact checking” for the memory system.

But repetition can do something even more uncanny and unusual. The opposite of déjà vu is “jamais vu”, when something you know to be familiar feels unreal or novel in some way. In our recent research, which has just won an Ig Nobel award for literature, we investigated the mechanism behind the phenomenon.

Jamais vu may involve looking at a familiar face and finding it suddenly unusual or unknown. Musicians have it momentarily – losing their way in a very familiar passage of music. You may have had it going to a familiar place and becoming disorientated or seeing it with “new eyes”.

It’s an experience which is even rarer than déjà vu and perhaps even more unusual and unsettling. When you ask people to describe it in questionnaires about experiences in daily life they give accounts like: “While writing in my exams, I write a word correctly like ‘appetite’ but I keep looking at the word over and over again because I have second thoughts that it might be wrong.”

In daily life, it can be provoked by repetition or staring, but it needn’t be. One of us, Akira, has had it driving on the motorway, necessitating that he pull over onto the hard shoulder to allow his unfamiliarity with the pedals and the steering wheel to “reset”. Thankfully, in the wild, it’s rare.

Simple set up

We don’t know much about jamais vu. But we guessed it would be pretty easy to induce in the laboratory. If you just ask someone to repeat something over and over, they often find it becomes meaningless and confusing.

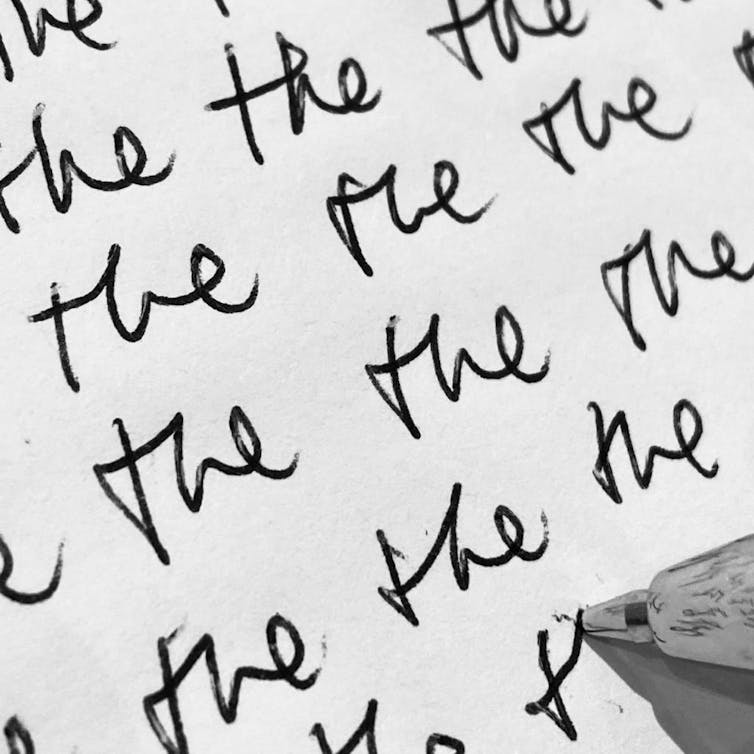

This was the basic design of our experiments on jamais vu. In a first experiment, 94 undergraduates spent their time repeatedly writing the same word. They did it with twelve different words which ranged from the commonplace, such as “door”, to less common, such as “sward”.

We asked participants to copy out the word as quickly as possible, but told them they were allowed to stop, and gave them a few reasons why they might stop including feeling peculiar, being bored or their hand hurting. Stopping because things began to feel strange was the most common option chosen, with about 70% stopping at least once for feeling something we defined as jamais vu. This usually occured after about one minute (33 repetitions) – and typically for familiar words.

In a second experiment we used only the word “the”, figuring that it was the most common. This time, 55% of people stopped writing for reasons consistent with our definition of jamais vu (but after 27 repetitions).

People described their experiences as ranging from “They lose their meaning the more you look at them” to “seemed to lose control of hand” and our favourite “it doesn’t seem right, almost looks like it’s not really a word but someone’s tricked me into thinking it is.”

It took us around 15 years to write up and publish this scientific work. In 2003, we were acting on a hunch that people would feel weird while repeatedly writing a word. One of us, Chris, had noticed that the lines he had been asked to repeatedly write as a punishment at secondary school made him feel strange – as if it weren’t real.

It took 15 years because we weren’t as clever as we thought we were. It wasn’t the novelty that we thought it was. In 1907, one of psychology’s unsung founding figures, Margaret Floy Washburn, published an experiment with one of her students which showed the “loss of associative power” in words that were stared at for three minutes. The words became strange, lost their meaning and became fragmented over time.

We had reinvented the wheel. Such introspective methods and investigations had simply fallen out of favour in psychology.

Deeper insights

Our unique contribution is the idea that transformations and losses of meaning in repetition are accompanied by a particular feeling – jamais vu. Jamais vu is a signal to you that something has become too automatic, too fluent, too repetitive. It helps us “snap out” of our current processing, and the feeling of unreality is in fact a reality check.

It makes sense that this has to happen. Our cognitive systems must stay flexible, allowing us to direct our attention to wherever is needed rather than getting lost in repetitive tasks for too long.

We are only beginning to understand jamais vu. The main scientific account is of “satiation” – the overloading of a representation until it becomes nonsensical. Related ideas include the “verbal transformation effect” whereby repeating a word over and over activates so-called neighbours so that you start off listening to the looped word “tress” over and over, but then listeners report hearing “dress,” “stress,” or “florist”.

It also seems related to research into obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), which looked at the effect of compulsively staring at objects, such as lit gas rings. Like repeatedly writing, the effects are strange and mean that reality begins to slip, but this might help us understand and treat OCD. If repeatedly checking the door is locked makes the task meaningless, it will mean that it is difficult to know if the door is locked, and so a vicious cycle starts.

Ultimately, we are flattered to have been awarded the Ig Nobel prize for literature. The winners of these prizes contribute scientific works which “make you laugh and then make you think”. Hopefully our work on jamais vu will inspire more research and even greater insights in the near future.