On the evening of August 8, a 16-year-old Pakistani kid named Sumail Hassan laid down his headphones and stepped away from his computer where he’d been playing a video game called Dota 2. Fireworks exploded around him. He hugged the friends he’d been playing with. They had just won $6.6 million.

With a neck pillow perched around the back of his head, gum in his mouth, and a dazed look on his face, he descended the steps from a glass booth in the center of Seattle’s KeyArena. Four and a half million people watched on screens around the world as he shook hands with his defeated opponents, before walking to the middle of the podium and raising the trophy above his head.

“What does this mean to you?” the host of the tournament, Kaci Aitchison asked him, thrusting a microphone into his face.

“It just means everything for me. We got it now. I’m feeling pretty excited,” he babbled, a little incoherently.

You can hardly blame him. Hassan’s family of eight had moved from Karachi to Illinois just three years beforehand. Crammed into a three-bedroom apartment, with money tight, they found the move a struggle. But in his first month in the United States, Hassan had already earned $200,000 in prize money.

He’d been playing Dota 2 since the age of 7, encouraged by his brother Yawar, who also plays professionally. In the world of Dota, teams of five characters fight to be the first to knock over a building in the enemy’s base called an ‘Ancient’, but that doesn’t explain the half of it.

In just one battle, a bleeping globe of light could teleport a demonic horsemaninto the fray while a sea monster causes tentacles to erupt from the ground — all while a relentlessly-grinning disco thespian zaps his enemies with lightning-infused clones of himself. It’s ridiculous, fast and furious, and simultaneously rewards both deep strategic thought and supersonic reflexes.

An online tournament is held every other week or so, where fans can watch matches through services like YouTube and Twitch, accompanied by professional commentators who explain the intricacies of different strategies. Every month or two, a larger tournament is held in a stadium where teams are flown in to from around the globe and players can enjoy the atmosphere in person, with huge screens depicting what’s going on in the game.

In less than a month, Sumail and his team Evil Geniuses will return to defend their title, but it won’t be easy. Since their win in Seattle, the team has been rocked by internal strife and the departure of several key players. They crashed out in 13th place at a tournament in Manila just a month ago, but just like in any sport, losses show the real strength of a team. Soon, we’ll find out whether Sumail and his teammates have the grit and determination to pull it back, or whether it’s time for a new squad to step into the limelight.

People have been playing video games competitively for many decades. The earliest known competition dates all the way back to Spacewar, one of the first ever video games, where players take on the role of one of two ships and engage in a dogfight around the gravity well of a star. An “Intergalactic Spacewar Olympics” took place at Stanford University on October 19, 1972. First prize, which went to team champions Slim Tovar and Robert E. Maas, and free-for-all winner Bruce Baumgart, was a year’s subscription to Rolling Stone.

In 1980, Atari organized a Space Invaders championship that attracted more than 10,000 participants, and, around the same time, an American businessman named Walter Day founded an organization called Twin Galaxies to keep track of high scores in arcade games. By 1982, video game tournaments were already being televised on the show Starcade, and particularly skilled players were featured in the pages of magazines like Lifeand Time.

Netrek — a 16-player, real-time strategy game that could be played across the web—debuted in 1988. Players had to destroy their opponents’ spaceships and take over enemy planets. Wired described it as “the first online sports game.” A year later in 1994, players competed at the World Game Championships in digital analogs of real-world sports, like NBA Jam and Virtual Racing.

But it wasn’t until the second half of the 1990s that e-sports really became a phenomenon in its own right. Titles like Quake, Unreal Tournament, Counter-Strike, and Warcraft grew hugely in popularity thanks to their multiplayer focus, and skilled players like Stevie “KillCreek” Case, Johnathan “Fatal1ty” Wendel, and Tomo Ohira began to earn serious money for winning competitions. Sponsors began offering players money to wear their logos or use their equipment while playing.

Around the same time all this was going on in the West, the 1997 Asian financial crisis was in full swing. Many governments responded by beginning large infrastructure projects, including the rollout of new broadband technology capable of far faster connection speeds than the modems that had been common previously. At the same time, high unemployment rates meant there were large numbers of people looking for something to do while out of work.

The result was massive growth in the pastime of playing games at internet cafes. Players competed over different games, with a real-time strategy title called Starcraft proving particularly popular. Soon, East Asia (and particularly South Korea) had a huge e-sports scene of its own with matches regularly broadcast on television. In 2000, the Korean E-sports Association was founded as a wing of the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism.

Elsewhere, however, mainstream acceptance of video games as a sport didn’t come nearly as fast as acceptance of them as a cultural force. In the West, mass-market adoption of games consoles like the Playstation and Xbox reduced the influence of e-sports, which are mostly PC-based. In the mid-2000s there were several sporadic attempts to broadcast matches on television in Europe and the United States, but most proved short-lived.

The rise of streaming video, however, changed everything. With the launch of services like YouTube and (gaming-specific streaming site) Twitch.tv, it suddenly became easy to follow a tournament being played on the other side of the world. It also allowed notable players to broadcast their games live, giving them another opportunity to sell sponsorship and make a living. Commentators, or “casters” as they’re known within e-sports, began to attract followings of their own.

Since then, the growth of e-sports has been extraordinary. Streaming video has allowed the scene to get so huge that mainstream acceptance is no longer a consideration, let alone a priority, for most players and fans. They don’t care if it’s on television or not, because watching a game on Twitch is a superior experience anyway — you can watch at a time that suits you, pause in the middle of the action, discuss the game in an accompanying chat room and more. Without Twitch, which Amazon bought in 2014 for close to $1bn, e-sports would be a shadow of its present-day strength.

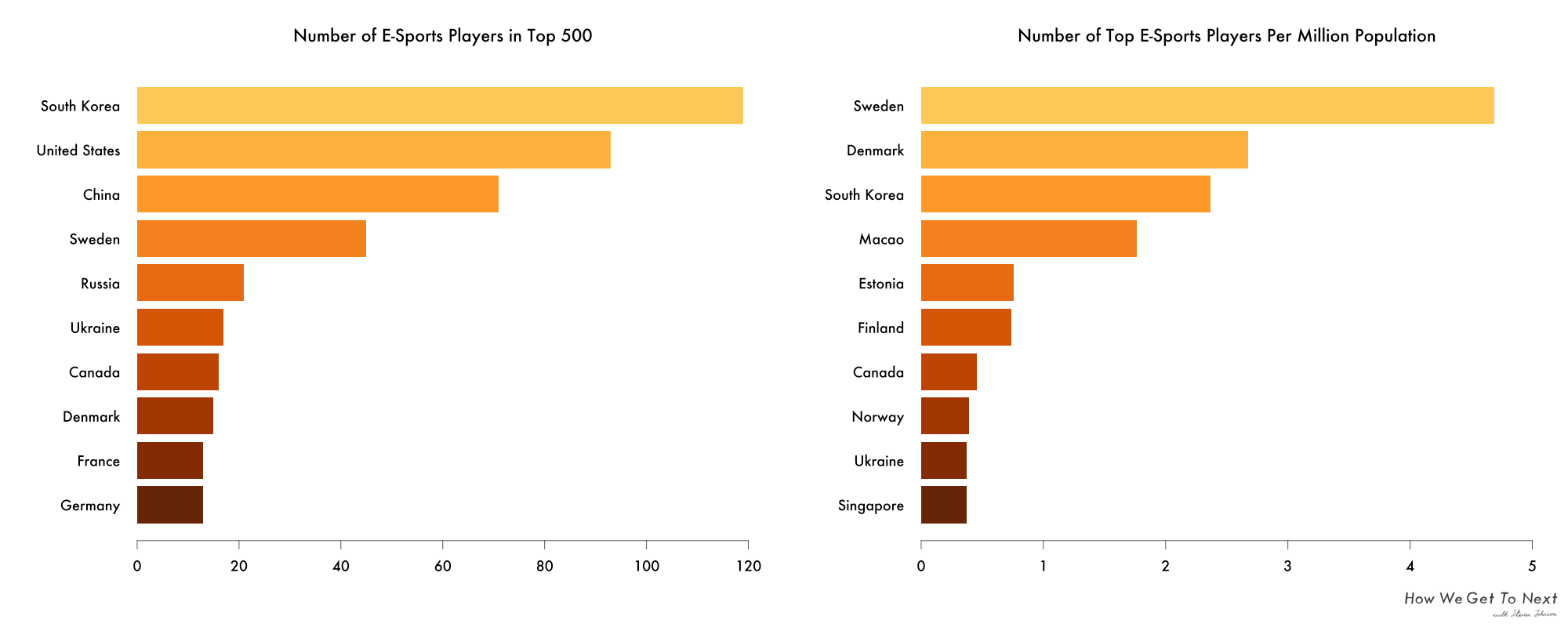

What’s particularly interesting about e-sports is how it’s distributed around the world. Some nations excel in digital battle, while their neighboring countries totally fail to do so. To get a grip on how, I grabbed data from E-Sports Earnings — a community-driven website which tracks publicly-available data on prize winnings across different games. While it doesn’t include, for example, a player’s sponsorship income, it gives a good idea of how prizes are distributed and therefore the level of success that different players have enjoyed.

Here are a couple of charts based on the world’s top 500 e-sports earners, aggregated by country. When you look at the number of players each country has in the top 500, South Korea, the US and China dominate. That’s not too surprising, with their large populations. So I divided my database by population and found something rather interesting — the Nordic nations dominate instead. South Korea still ranks highly (thanks to its early investment in broadband) but northern European nations score significantly better. In Sweden, if you took a million people at random from the population, almost five of them would be professional e-sports players.

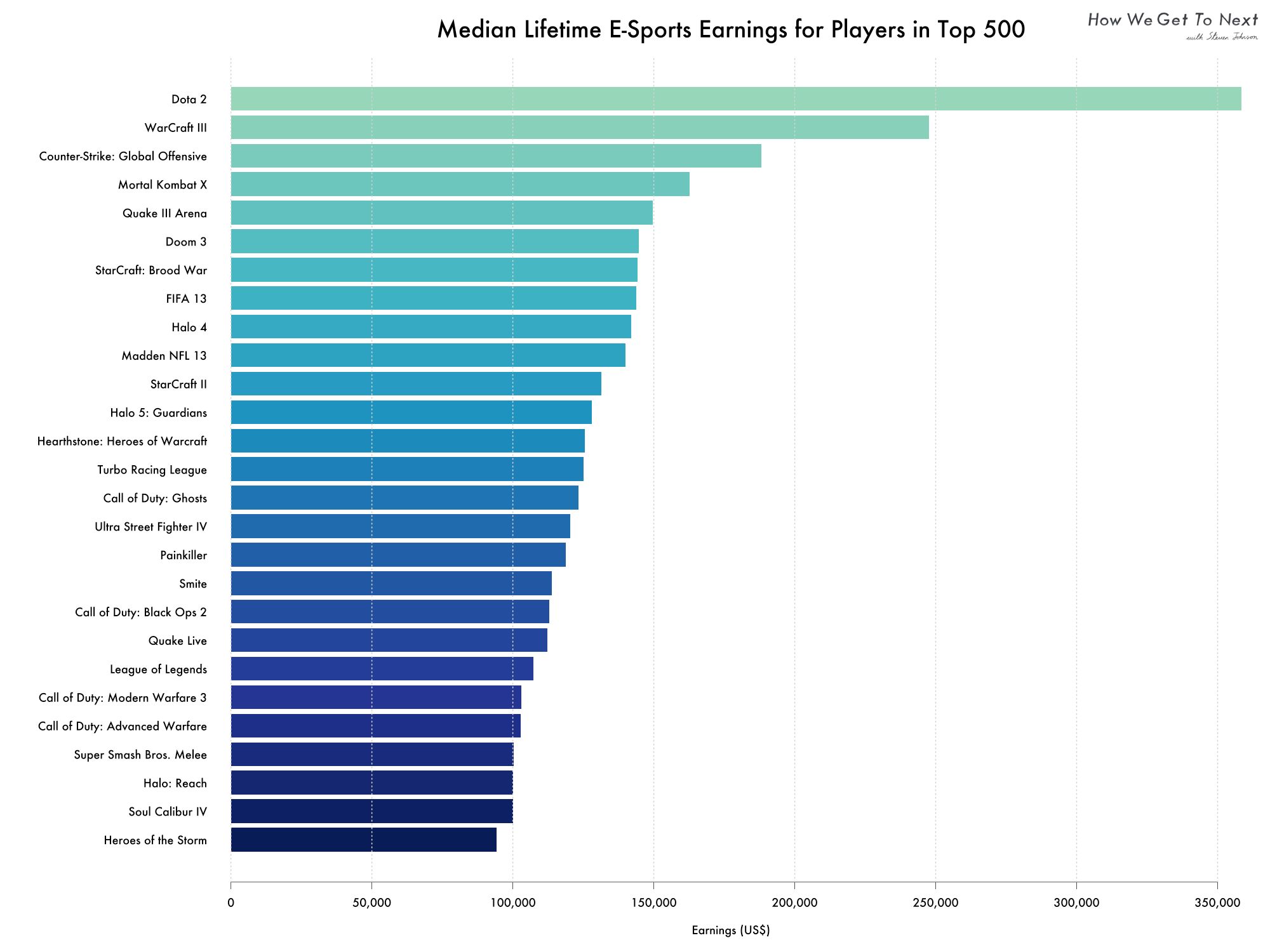

So let’s say you were a young, skilled player (perhaps living in a Nordic country) and you wanted to “go pro” to earn piles of cash. Statistically speaking, you’d want to play Dota 2 — E-sports Earnings’ data shows that it has by far the highest median lifetime earnings than any other game — more than $350,000.

Dota 2 tournaments simply pay better, and the reason for that is because amateur players contribute to its largest prize pools. Dota is totally free to play, though you can pay to customize the appearance of your characters, and a few other cosmetic tweaks. A few times a year, its publisher Valve Software also sells a ‘Battle Pass’ that includes a bundle of customization options, and 25 percent of the cost of each pass goes into the prize pool. In August 2015, Valve offered up a prize pool of $1.6 million for the tournament won by Evil Geniuses, but that swelled to $18.4 million once Battle Pass purchases were added.

Looking down the list of high-earning games is interesting, because it’s like looking back through history. Some of the titles are rising in popularity, some are falling, some are distinctly dead. But they’ve all had a major part to play in the sweeping narrative of e-sports over the years, with hundreds of players having given up substantial portions of their life to them. Some with success, some with failure, but all with profound love for their sport.

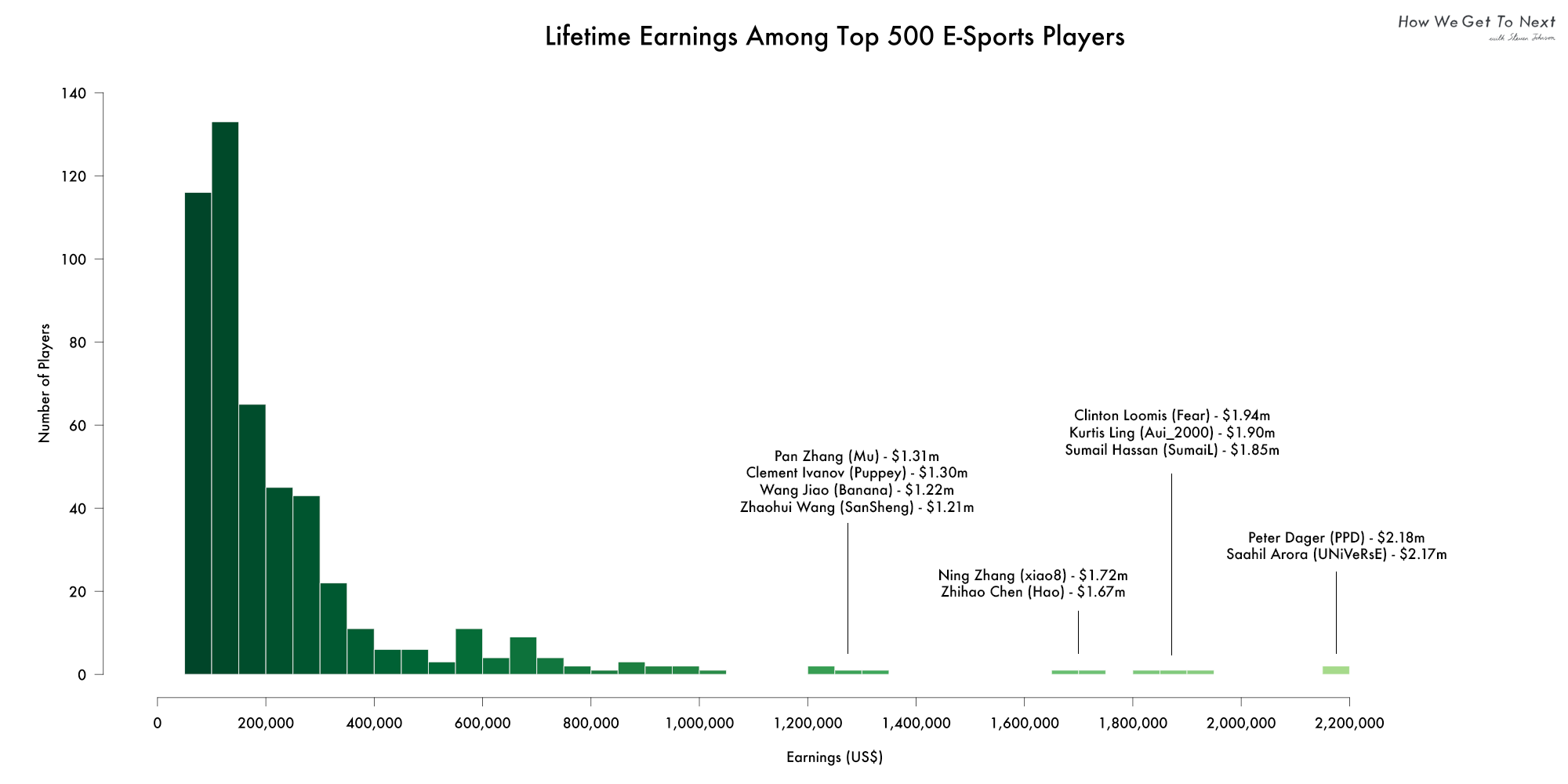

Let’s talk about success and failure. When you look at a histogram of lifetime earnings among the top 500 e-sports players, you can see that becoming a millionaire is not likely to happen for the overwhelming majority of players. According to the data from E-sports Earnings, most top players make less than 400,000 in prize money over their lifetime.

That lifetime of earnings is about as short as that of a traditional athlete. One of Sumail’s teammates in Evil Geniuses, Clinton ‘Fear’ Loomis, is known jokingly as the “old man of Dota”. He’s 28. Once past their mid-20s, most players either take up coaching or analyst roles, move into the business end of the industry, or retire from the scene entirely.

So while a young, skilled gamer who wants to drop out of university and go pro can now point their parents to multiple other stories of players who did the same and are now wealthy beyond belief, there are, of course, far more examples where it hasn’t worked out like that. Competition is more fierce than it has ever been and it today takes substantial personal investment and sacrifice to become a well-known player.

Unfortunately, that means cheating scandals in e-sports are about as common as they are in real sports. Even though most major competitions now have officials monitoring for unauthorized hardware or software running on a computer, many high-tier players have been banned and even fined over the years for cheating or fixing matches for profit.

That’s not the only problematic issue that e-sports has in common with “regular” sports. Doping has become a recent topic of debate, with many players using stimulants to boost concentration and reaction times, or sedatives to remain calm under pressure. One e-sports executive recently admitted that it’s common for some players to take as many as three different drugs before a competition.

It’s also hard to avoid noticing that the e-sports scene is almost entirely male. Gendered harassment, sexism, and homophobia are commonly seen as part of the culture, even by some pro players. The few female pros that have found success are often characterized as having done so “in spite of” their gender, and there are only a handful of openly gay players. Not enough high-profile figures are willing to challenge the status quo in this regard, in fear of the backlash they might receive from fans, and as a result it’s hard to see this changing in the future. Being an e-sports fan too often involves turning a blind eye to unpleasant behavior.

I got into e-sports a little over four years ago. Some friends and I were in a pub discussing a game called Dota 2 that we’d all heard about but no one had actually played. We resolved to give it a try (one of my friends chronicled the hilarious results here), and it somehow stuck with me for much longer than most other games. I discovered that beyond the steep learning curve lay a complex tapestry of game mechanics, obscure knowledge, and lightning-fast reflexes. It was a game I could learn but never master. I loved it, and within a year I was watching pro gamers play on Twitch and YouTube.

To date, I’ve played more than 880 hours of Dota 2, but I must have spent far, far longer than that watching other people play it online. Once or twice a week I’ll spend a lunchtime watching one of my favorite teams (go Alliance!) play a match. Often I’ll have it on in the background, muted on the TV, while I work. When a big tournament is on and Alliance is playing, I’ll sometimes decline social invitations because I want to watch them live. I don’t tell people that, of course. It’s seen as somehow weird to stay home and watch people playing a video game—despite it being totally fine to stay home and watch football.

I’ve branched out occasionally to try and watch other e-sports. I went to the WCS 2012 Starcraft II finals in Stockholm and enjoyed it tremendously, but it never hooked me enough to keep me following the scene. I’ve watched a little bit of Counter Strike: Global Offensive and Rocket League when it’s been on, more out of curiosity than anything else, and they were entertaining, but it’s tricky to find the time to follow more than one game with any real commitment, and Dota is the one I know well. I’ve invested time in learning it, and I’m enjoying the rewards of that investment.

So in closing, I should probably recommend a few e-sports to get into for those of you who are curious enough to read got this far down the article. One common issue with spectating many e-sports is that it’s hard to get a good feeling of what’s going on unless you’ve played a little yourself. So if in doubt, go with what looks like it would be most fun to play.

Otherwise, if you have lots of time, Dota 2 is probably the biggest e-sport in the world right now. It’s deeper and more complex than its rivals, and requires a lot of investment from the viewer, but the rewards are huge. If you want to get a taste of how good it gets, watch the fifth match in the best-of-five grand final between Alliance and Na’vi in 2013. There’s a reason any game between those two teams is referred to as Dota’s very own El Clásico.

If you prefer something more traditionally game-like, look into Hearthstone — a digital card game published by Blizzard Entertainment. It’s growing fast, and matches tend to last only a few minutes, making it easier to fit into your day. You can also play it on tablet computers, for when you’re bored at work. Start out by watching this ThijsNL play Savjz at KFC Spring in 2015, with the former battling for his life in a nail-biter of a match.

Finally, if you prefer less of a time investment and want something you can understand immediately, try Rocket League. It’s football with cars in microgravity, and doesn’t get a lot more complicated than that. In 2015, Cosmic Aftershock played Kings of Urban in the grand finals of MLG. The prize pool was just $500, but it didn’t stop both teams playing out of their minds. You’ll be on the edge of your seat.

Now, over to you. I’m sure you have your own ideas about what e-sports people should get into (especially if you play League of Legends and are annoyed that I spent most of this article banging on about Dota). Leave me a comment below with your experiences of e-sports and your recommendations of games for new viewers to enjoy.

____________________________________________

About the Author

This article was written by Duncan Geere, Gothenburg-based science, technology and culture journalist. He is a data Editor at howwegettonext.com. Email him.