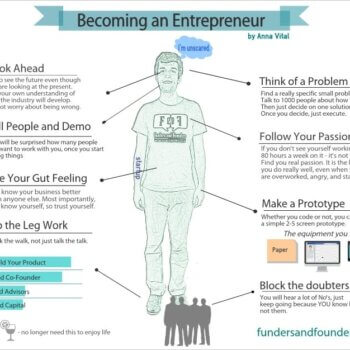

I’ve spent the past 15 years researching people who start companies, and there’s a consistent theme among the 16,000 founders I’ve analyzed. It’s passion. Founders believe in their ideas so strongly they throw aside comfortable jobs and risk their life savings to chase their dreams. They have such contagious enthusiasm they can convince others to sign on, whether it’s co-founders or venture investors or early-adopting customers.

But that’s the positive side of passion. Another constant I’ve seen is that if there’s anything that can sink a new business, it’s passion. It blinds entrepreneurs, leading them to get overconfident and make bad choices at the worst times—potentially dooming even the most promising startups. Only then do founders appreciate that the origin of the word “passion” is the Latin word for “suffer.”

Passionate entrepreneurs are so impatient to move forward with their brilliant new idea that they get too optimistic about how would-be customers and investors will see it. Since founders are so committed to the enterprise, they end up blindsided when key team members lose interest and drop out. They don’t realize they lack the skills and support they need to get a business on its feet. And they can’t imagine that investors will want to replace them with a more-seasoned CEO.

Here’s a road map of four critical junctures where founders often let passion cloud their judgment—and strategies for staying clear-eyed.

THE LAUNCH: Let’s Do It ASAP!

The first time passion can cause problems is when aspiring entrepreneurs are deciding whether or not to launch a startup. They can get blinded into believing all the factors are favorable for starting a company, making them much more likely to take undue risks.

Let’s break that down. There are three major areas prospective founders need to take into account when they’re thinking about launching—their market circumstances, their career circumstances and their personal circumstances.

In the market realm, a founder who’s passionate about an idea is more likely to misread whether a large potential customer base for their venture exists. Obsessed with their own ideas, founders are at risk of believing that “I would love to buy this product, so there must be a lot of others who would, too.”

For instance, almost 800 founders took a predictive test that evaluated their startup ideas, then received recommendations about the next steps they ought to take. Thomas Astebro and his colleagues found that a sizable percentage of founders who received a recommendation to halt progress on their startups because the idea wasn’t commercially viable kept going anyway—29% of this group kept spending money, and 51% kept spending time, developing their idea. On average, they doubled their losses before giving up on pursuing their idea. To explain why a significant proportion of founders kept going after receiving negative feedback, the study’s authors point to optimism (as well as to the sunk-cost effect, the tendency people have not to abandon something after they’ve sunk money into it).

When it comes to career circumstances, passion often blinds founders into thinking they have all the skills they need to build their business, when in fact they’re poorly prepared—and may not be able to fill in the gaps on the fly. Likewise, passionate founders may not realize they don’t have the connections they need to help find co-founders, employees or investors.

I recently surveyed 100 Harvard Business School graduates who had become founders over the past decade. Their reflections indicated that the biggest thing they lacked at the time of founding was sales experience, followed by technical/scientific experience and management experience. Next came connections: Their fourth and sixth biggest holes were contacts with investors and with potential customers.

Finally, in the personal realm, aspiring entrepreneurs may discount the toll that a startup will take on their family, and they are more likely to sell a significant other on rosy scenarios in order to gain their support.

Serial entrepreneur Steve Blank describes four lies that entrepreneurs tell themselves and their spouses. Lies they tell themselves include “I’m only doing it for my family” and “my spouse ‘understands.’ ” Lies that are also told to spouses are “all I need is one startup to ‘hit’ and then I can slow down or retire” and “I’ll make it up by spending ‘quality time’ with my wife/kids.”

Steve admits that he told himself each of these things, and “none of these were true.”

Down the road, fragile early support from a spouse is likely to crack as the venture hits bumps—and strong emotional backing is most needed.

THE BUSINESS PLAN: The Bigger the Better!

Next, passion can wreak havoc with founders’ judgment when they’re crafting their early business plans. They focus on rosy scenarios, assuming they’ll get up and running quickly and build sales without a hitch.

When researcher Arnold C. Cooper and colleagues asked 3,000 small-business owners about the odds of success for their own businesses, they ranked their own chances as being an average of 8.1 out of 10. When asked about the odds of success for businesses similar to their own, they ranked them as being much lower: 5.9 out of 10.

Needless to say, the rosy projections rarely pan out. Back to my survey of Harvard Business School founder-alums. When asked how their actual execution compared with their early plans, the largest percentage—41%—said that their ventures ultimately ended up taking at least “twice as long and twice as much capital” as they had planned. For a total of 79%, execution was slower than planned. Only 4% of the plans were on target.

For another perspective, consider research from Keith M. Hmieleski and Robert A. Baron. They found that optimism at startups—”the tendency to expect positive outcomes even when such expectations are not rationally justified”—was associated with a 20% decrease in revenue growth and a 25% decrease in employment growth over the subsequent two years. The more fast-moving and quickly evolving the startup’s environment, the stronger this effect was.

The authors point out that optimism isn’t always a negative when building a business, but founders should find effective ways of tempering that rosy view with a dose of realism.

DIVIDING EQUITY: We’re All in This Together!

When a passionate entrepreneur brings together a team to help run a startup, it’s easy to get caught up in the enthusiasm of the project and assume the best. Everyone will be a great fit and have the skills the company needs as it grows, the entrepreneur thinks, and will maintain the same level of commitment over the long haul. The Three Musketeers forever.

All too often, founders craft agreements and contracts in that frame of mind. And it comes back to haunt the team down the road. Things change, often dramatically.

As the company grows and evolves, one partner’s strengths are needed more than anticipated, so he ends up taking a larger role. Another partner loses interest with the venture and stops contributing as much. Another has family problems and needs to drop out for extended stretches.

But all of them are still working under the contracts that they crafted during the early Three Musketeers days. My data show that 73% of teams split the equity ownership within that enthusiastic first month of founding, and a majority of those teams engrave their ownership percentages in stone; their initial split will remain, no matter what develops.

That inflexibility in the face of change leads to tension. Over time, my research shows, unhappiness with the initial equity split nearly triples. And undoing a bad early split is hard to do.

THE CEO CHAIR: I’ll Run the Show Forever!

The final big juncture comes when the startup has gotten off the ground.

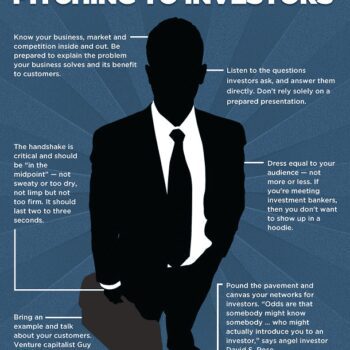

Passionate entrepreneurs have led their enterprise past some big milestones and are getting more confident in their abilities. They get so confident, they figure they can keep the reins forever. And very often they’re shocked when a big investor or the board of directors wants to replace them with a new CEO.

My data show that by the time startups raise the third round of outside financing, 52% of founders have been replaced as CEO. Three-quarters of the time, the founder didn’t want to go.

There are good reasons for replacing a founder at the top. The skills it takes to build an excellent product and go from no sales to $1 million aren’t the same ones needed to hit $10 million or $100 million. But even the most rational arguments for a change at the top often fall on deaf ears.

When founders are blindsided, the transition to a new CEO may instead harm value and heighten risks. After all, if the “fearless leader” is furious about being fired, distraction and turnover are likely to increase for early employees and loyalists. And when founders insist on retaining the throne, they usually scare off the investors and hires whose capital and contributions can help build the company’s value.

Avoiding all of these traps isn’t easy.

Even after seeing the statistics on entrepreneurial missteps, many passionate founders tend to believe, “That won’t be me; I’ll avoid those problems.” Culturally, founders are celebrated for following their natural inclinations and their intuition.

However, as Steve Jobs warned, “Follow your heart, but check it with your head.” Founders should educate themselves about the decisions and hurdles they are likely to face.

Even in the idea stage, entrepreneurs must recognize that their passion may be blinding them, and they need to take steps to get the skills and support they need—not just assume they will “find a way.” A mentor who excels at being a devil’s advocate, for instance, can help come up with worst-case scenarios for the business and then help prepare plans to avoid them.

Potential founders also need to take a clear, critical look at themselves and figure out their points of weakness—do they lack skills in a certain area? Will they be able to withstand an extra year without a salary? Do they have the contacts that they’ll need to land customers?—and then address those holes through proactive planning, training and networking.

Likewise, founders need to assume their relationships with their partners will change, as will each co-founder’s suitability and commitment, and develop agreements that are flexible enough to adjust.

Then there’s the question of how to prepare to be replaced as CEO. As they embark on their journeys, founders should reflect on what they want for themselves.

Do they want to see their “baby” grow as large as possible? In that case, they should ready themselves to step aside and figure out what kind of secondary role will satisfy them. Or do they want to remain in charge at all costs? Then they must prepare themselves to lead a company that won’t attract as much talent and investor interest. They’ll still be king or queen, but over a much smaller kingdom.

By identifying common pitfalls and proactively taking action to avoid unwanted outcomes, founders are much more likely to build the type of company they seek and to achieve the impact on the world that we all need them to have.

This article was written by Stephen Webster from Wall Street Journal

Mr. Wasserman, a professor at Harvard Business School and a visiting professor at the Stanford School of Engineering, is the author of “The Founder’s Dilemmas: Anticipating and Avoiding the Pitfalls That Can Sink a Startup.” He can be reached at[email protected].