Key Takeaway:

George Bernard Shaw referred to Ebenezer Howard’s “garden cities” concept in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which he believed would offer the advantages of town and country without the drawbacks. Recently, a Silicon Valley consortium called Flannery Associates purchased land for California Forever, a contentious project that echoes Howard’s ideas. Howard’s ideas focused on social reform, regional production, self-sufficient communities, and circular economy principles. However, his ideas were later criticized for their propensity towards authoritarianism and anti-urban tendencies. The California Forever project may have influenced the financial considerations of the project, but it is heartening to see organizations like Silicon Valley investors champion the advantages of sound urban planning and the opportunities it presents for future generations. However, the current planning systems are not as progressive, and the private sector’s involvement in such initiatives raises questions about the role of the private sector in urban planning.

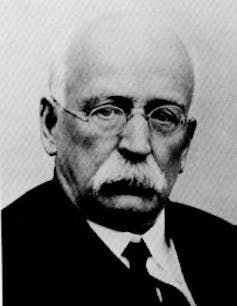

“One of those heroic simpletons who do big things whilst our prominent worldlings are explaining why they are Utopian and impossible,” George Bernard Shaw once said of him.

The renowned playwright was alluding to Ebenezer Howard’s theories, who developed the concept of “garden cities” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Howard contended that these new urban areas would have all the advantages of town and country, but without the drawbacks.

The recent reports of a Silicon Valley consortium called Flannery Associates purchasing land to build a new city in Solano County, northern California, serve as a reminder of that somewhat belated compliment. California Forever, the parent company of the investment vehicle, is the name of the contentious project.

It is easy to see the similarities between Howard’s concepts from over a century ago and modern utopian thought. Although it might seem innovative, the idea of something like California Forever is ingrained in the systems of planning that exist today.

In fact, Howard’s ideas were so appealing to H.G. Wells, the science-fiction writer and futurist whose own ideas would resonate with many in Silicon Valley, that Wells joined the Garden City Association to support Howard’s creation.

Green city visions

New city models of all kinds often mirror the political views of their founders. The plans and vision go beyond the physical structure to depict a desired way of life and relationships with the natural world and one another.

The artwork that goes with the California Forever project presents a beautiful, peaceful scene that is recognisable to utopian visions: lots of parks, open areas, and renewable energy.

It captures an urban politics that highlights the need to reframe our interactions with the natural world. Because of this, these concepts also heavily rely on social engineering. They envision a new kind of society that is superior to the one we currently live in, not just a new built environment.

However, the garden cities that were eventually built were nothing like Howard’s original idea. Indeed, his ideas from more than a century ago seem decidedly out of date compared to those from Silicon Valley.

For Howard, the importance of social reform and organisation was equal to that of urban planning. In order to lessen the need for travel, he promoted regional production, comparatively self-sufficient communities, and creative waste management techniques that are in line with the principles of the circular economy.

Planning and profit

Even less like the logic of investment behind California Forever, Howard also envisioned a city capable of subverting certain capitalist principles.

He promoted the cooperative organisation of land in garden cities as a means of sharing wealth and reducing poverty, in light of the stark deprivation and social divide between the haves and have-nots.

A contributing factor to the erosion of Howard’s ambitious politics was the need to draw in investors. Large sums of money are needed to buy land on that scale, and those who contribute the money would undoubtedly be hoping for a profit.

History would warn us that, should California Forever come to pass, there might be a similar gulf between rhetoric and reality. Although some of Howard’s concepts were partially adopted in locales such as Letchworth, the built environment was given greater importance than sustainability or social justice.

After moving to the new city, Howard found that his influence was reduced due to the necessity of catering to the interests of shareholders.

Although the exact nature of California Forever’s sales pitch is unknown, it is reasonable to assume that financial considerations such as purchasing less expensive farmland, rezoning for homes and other development, obtaining state funding for infrastructure, and realising property appreciation have influenced the project.

Even though the pictures seem sustainable, given the state of the California labour market, long-distance driving and expectations of true community involvement in the project could present challenges. Utopian plans have long been criticised for their propensity towards authoritarianism, a criticism that the tech industry has faced recently.

Critics also criticised Howard’s ideas for being anti-urban. Instead of leaving behind and starting over, perhaps to build a gentrified enclave, shouldn’t we aim to make the cities we already have better?

There is a persistent utopian tendency in the tech industry as well, one that prioritises emigration (to new cities or moon colonies) over applying its immense wealth and power to solve contemporary urban issues.

Progress and planning

In the end, though, it’s heartening to see organisations like the Silicon Valley investors champion the advantages of sound urban planning and the opportunities it presents for coming generations. The fact that the planning systems in place today are not nearly as progressive is the main issue.

Similar powerful investors frequently criticise urban planning in many other countries, claiming that it creates “red tape,” raises development costs, or prevents markets from operating “efficiently.”

However, the kind of city-building that California Forever advocates calls for more authority in the regulatory domain and the kind of political aspiration that was more typical a century ago. It also begs the question of whether the private sector ought to be involved in initiatives such as these.

Perhaps at the very least, these kinds of projects offer a chance to reconsider the possibilities of urban planning and shed light on contemporary social issues. Howard’s utopian vision was intended to address the issues of the day, which included extreme wealth disparities, slums, polluted cities, and rapacious landlords.

The inspiration behind the concept shows that history rhymes sometimes even if it doesn’t always repeat itself, whether or not California Forever is constructed.