Because my original article regarding The Dark Forest Theory has been one of my most beloved, I thought it would be an interesting new addition to have it illustrated for my readers. I worked alongside professional artist Nicole Bowden to bring you this visual guide. I hope all of you find it helpful and entertaining to read.

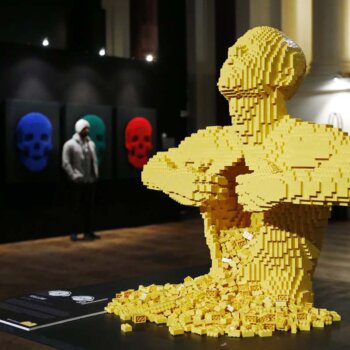

It’s a pleasant night in the city. There’s a cool wind and a luminous moon overhead. You’re on your way back home through the empty roads, walking in the unsettling silence. It’s unsettling because it’s deep night — the time when dangerous people come out to look for victims. It’s the time for drug deals and murders, for kidnappings and theft. Seeing the familiar figure of another person standing just down the street from you is a heart-pounding affair. There’s no clear way to tell their intentions.

Walking beneath the electric lights draws attention to yourself so the safest option is to keep hidden, avoiding people and assuming the worst of them until daylight arrives. But there’s a difference between the cityscape of Earth and the cosmic streets of the universe: in the universe daylight will never come. There’s no locked home to go to and no policemen to seek out for safety. There’s only the potential for danger, and the inability to know the other civilization’s true intent.

The above thought experiment was written years before the Dark Forest theory, appearing first in the hard science fiction novel The Killing Star by Charles R. Pellegrino and George Zebrowski. It asks the reader to agree to two things.

The first is that a species’ own survival is more important than the survival of another species. That is, to us humans the survival of humanity will always come before the survival of an alien race. The second thing we must agree to is that a species which has come together to ascertain themselves on their own planet will have some level of aggression and alertness. It’s certainly something which has proven true on Earth. In order to survive, humans have imposed upon other tribes, other animals, and upon the planet itself. If these two conditions are true of ourselves — and we assume them to be true of the other species — then they will assume it to be true of us as well. This can be a problematic manner of thinking. It leaves always on the horizon the potential for conflict.

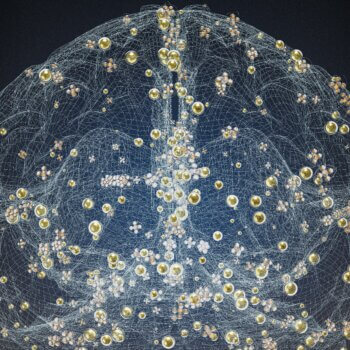

But this scenario is a bit different in the Dark Forest theory. It’s a concept which arises from Liu Cixin’s novel The Dark Forest, a sequel to the award-winning Three Body Problem. In the novel the theory becomes an attempt to answer the question of the Fermi Paradox. It is, in short, an exploration of why we’ve so far seen no signs of alien life when we should statistically be able to see at least 10,000 of them in the universe. 20 of those alien civilizations should exist somewhere nearby.

These numbers come from the Drake equation, conceived by astronomer Frank Drake in 1961. The equation is an estimate of how many civilizations should exist in our galaxy by examining the many factors that might play a role in their development.

In The Dark Forest, the two assumptions of life are this: living organisms want to stay alive, and there is no way to know the true intentions of other lifeforms. Because there can be no certainties of a peaceful encounter, the safest course of action is to eradicate the other species before they have a chance to attack. This also explains why an alien society might want to stay quiet, reducing the risk of discovering that humanity, for example, is a hostile civilization.

The novel also brings up the point of limited resources. A civilization that wishes to continue expanding across the universe will need to compete for limited resources with any other intelligent life. With this assumption one need not even consider that the species is hostile. We endanger animal populations all the time, not out of hatred but out of need for their land.

“The universe is a dark forest. Every civilization is an armed hunter stalking through the trees like a ghost, gently pushing aside branches that block the path and trying to tread without sound. Even breathing is done with care. The hunter has to be careful, because everywhere in the forest are stealthy hunters like him. If he finds other life — another hunter, an angel or a demon, a delicate infant or a tottering old man, a fairy or a demigod — there’s only one thing he can do: open fire and eliminate them. In this forest, hell is other people. An eternal threat that any life that exposes its own existence will be swiftly wiped out. This is the picture of cosmic civilization. It’s the explanation for the Fermi Paradox.” An excerpt from Liu’s novel.

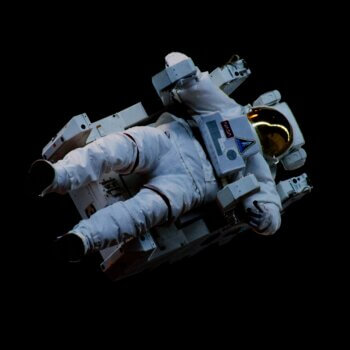

This concept is supported by physicist and NASA consultant David Brin. In fact, it would only take one civilization thinking this way to produce the lack of radio signals we’ve observed over the past century. As soon as other intelligent lifeforms discovered and began using radio, they would be eradicated by a more advanced civilization. But doesn’t this mean that humanity, too, is already doomed? Even beyond the purposeful signals we’ve sent into space in an attempt to communicate, we’ve also been giving off signals daily over the past few decades as we watch TV and use our phones. Signals that are just a product of our everyday life, however, tend to be faint and aimless, making them much less likely to give us away than a signal we consciously direct towards another planet.

But therein lies one of the problems with this theory. Is it possible to have a civilization that’s always completely silent? And even if it is, can this silence be guaranteed for long periods of time? If there was an alien civilization stalking the galaxy for any signs of life, surely they would have already detected Earth and decided to attack.

Unless they have detected Earth and exist camouflaged somewhere in the night sky, patient and observing. Another possible flaw in the Dark Forest theory is that these alien civilizations will not consider the value of alliances. As a species who had to come together to achieve interstellar travel, it is likely they’ll understand the rewards of cooperation and the possibility of trade — not just in resources, but in knowledge.

Historically, however, the possibility of alliances hasn’t stopped humans from warring with one another.

Liu answers these critiques of his theory by bringing up a chain of suspicion. Even if two societies were able to communicate, there would still be incredible distances to surmount, both physically and in terms of culture and language. If another civilization is younger than one’s own, they may seem to pose no threat at first but this wide distance and time span between the two worlds would mean an uncertainty in how fast the other civilization is evolving. Technology doesn’t follow a linear path. Instead it develops exponentially, turning a now harmless and young civilization into a threat as they advance in leaps.

When everything’s at stake, it’s easy to see why extraterrestrial lifeforms might view communication as too high-risk to entertain.

David Brin isn’t the only scientist to consider this a plausible scenario. Stephen Hawking and a roster of dozens of other scientists have also warned against searching so boldly for extraterrestrial life. A petition has been signed to prevent humans from actively sending signals into space and disclosing information about our society and our location. This opens up the discussion to the broader question: who can make the decision that we should be attempting to communicate with other beings? Who can decide on behalf of the planet as a whole?

The Dark Forest theory is an examination of life on Earth. It’s about how we treat one another, our propensity both for violence and for cooperation, our ability both to consider and to disregard life. The theory applies these characteristics to the great beyond.

One of the biggest consolations walking the streets of Earth at night is that even if one confronts another person, one can still appeal to their humanity. But that’s not a guarantee when addressing civilizations in space. Would it be better if their nature was similar to ours? Or should we hope to find a very different race of lifeforms? Perhaps we’ll find a society kinder and wiser than ours. Perhaps not.