What makes a person want to believe in God? Is it the many delicate, impressionable years of their youth spent at the crowded Sunday Mass? Is it the comfort derived from the words of a holy book within which is promised a paradise just beyond this taxing life? Or is it an experience in their life which changes them forever, an overwhelming moment of connection with a higher being and the universe around them? The answer is different for each person. Spirituality is a complex human phenomenon. It was sewn within our kind as far back as thousands of years ago when we were nothing more than families huddled ‘round on primitive Earth. Back then our spirituality manifested itself as drawings of animal-human figures on cave walls and elaborate burial ceremonies to part ways with the dead.

Perhaps what’s most surprising isn’t that spirituality has been around since the emergence of mankind, but that it has remained so prominent in the modern day. A 2017 survey found that 75% of Americans described themselves as spiritual. This isn’t to be confused with organized religion. The difference between religion and spirituality is that religion is an external show of faith — it’s embodied by places of worship and through community rituals such as a Baptism. Spirituality, on the other hand, is a private belief not necessarily encumbered by any rules or strict structure. It is faith expressed internally, a belief that one carries throughout one’s life that doesn’t have to be shared with other people. This is why church attendance may continue to fall while the number of people claiming to be spiritual can stay the same. Of course despite the differences the two are often intertwined.

In the early 2000’s geneticist Dean Hamer conducted research on religion and spirituality. The premise was a fascinating one: what if there was a genetic component to faith? The debate on whether God does or doesn’t exist may never have an answer, but we can at least try to understand why such a belief arose in the first place. It may be, just like our long fingers and cautious dispositions, that faith was coded into us because it benefited our species — nothing more than another example of Darwin’s theory of evolution. These faith genes or, as Hamer hesitantly calls them, “God genes” may have contributed to optimism which in turn helps people recover quicker from disease and maintain overall better health.

Hamer’s research involved scoring people using a self-transcendence scale. In psychology, self-transcendence is the ability to see one’s self as a small part of a greater whole. It is exactly what the word implies: a transcendence of the self in order to acknowledge something greater. This greater thing might be nature, the universe as a whole, the human soul, or a higher and more divine being sometimes called God. Scoring higher on the scale is associated with greater spirituality.

Prefacing Hamer’s experiments was the 1999 twin study carried out by a group of three scientists. The scientists separated identical twins from fraternal twins to better understand the role of genes in regards to feelings of self-transcendence. The scores of the identical twins were similar significantly more of the time than the scores of the fraternal twins. Because identical twins are twice as similar genetically, that is exactly the kind of result one would expect to see from a genetic trait. Environmental factors were not shown to have much of an impact on the self-transcendence scores. This meant that the study had arrived at one insightful conclusion: spirituality didn’t come from the environment. It was not a trait that was learned from any person or literature. Instead, spirituality as measured by the self-transcendence scale is something present from the moment of birth.

However, while those studies may have promoted the idea that faith has a genetic component, they did not reveal the exact genes responsible. This is what Hamer was attempting to do.

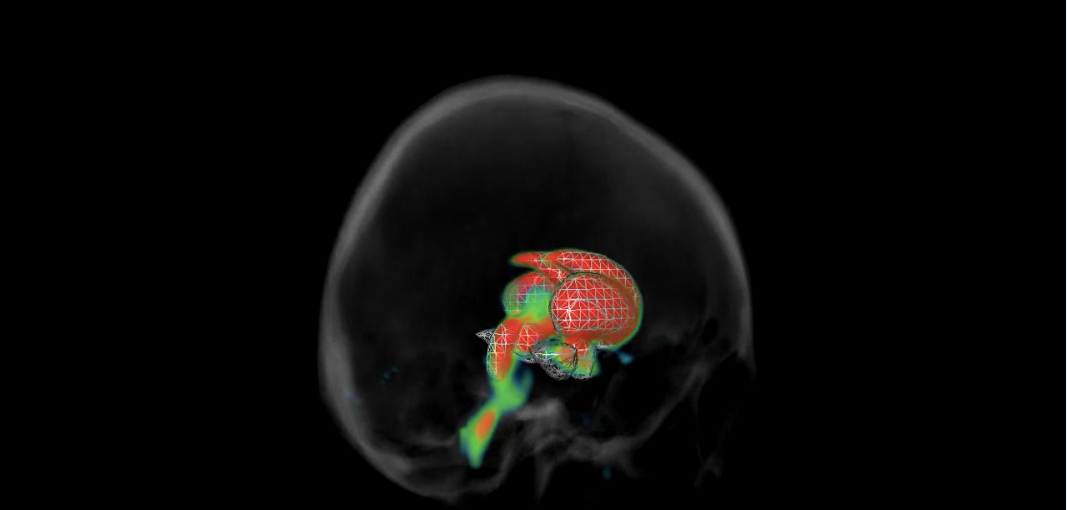

In a study with more than 2,000 DNA samples and over 200 questions to gauge participants’ spirituality, Hamer found that higher scores of self-transcendence corresponded to a greater likelihood of having one specific gene. The more spiritual a person was, the more likely they were of having the gene VMAT2. The gene itself is a protein responsible for regulating a number of chemicals in the brain. In more scientific terms, it’s known as a monoamine transporter. The same chemicals regulated by VMAT2 are also involved with mystical or divine experiences triggered by drugs. The monamines, or chemicals, play a large role in a person’s consciousness and how they perceive the world. This in turn is the foundation for spirituality. VMAT2 was not found to be related in any significant way to any other personality trait.

Is this the gene for faith, then? Can all our most ambitious beliefs be traced back down to a tiny unassuming code in our DNA?

No. VMAT2 may indeed play a critical role in each person’s faith. But it couldn’t possibly be the only gene involved. In fact, VMAT2 was responsible for such a small part of the self-transcendence score that Hamer estimates there must be at least another 50 genes playing just as big a role in a person’s faith. The “God gene” may be more of a string of genes. To date his study has not been replicated by another team.

And of course spirituality could never be said to be biological alone. If there are a series of genes which play a role in our faith then they are interwoven with the nuances of our upbringings and personal experiences. Genes may influence a person towards becoming spiritual, but spirituality itself is not purely genetic. Why we developed this inclination towards spirituality may have roots in evolutionary theory: faith encourages better physical and mental health, making us better overall people.

The idea of faith genes and their part in evolution remains controversial among scientists. They are a hypothesis, though confirmation of their existence might not do much to sway people’s opinions one way or another. Atheists and non-spiritual people will use the faith genes to reduce spirituality and religion down to the clinical. Beliefs are nothing more than a mechanism by which our species survived. Those who believe in a higher power will cite the faith genes as a clever creation of God. They are the mechanism we inherited in order to better communicate and become part of the heavenly world above us.

At the end of the day Hamer’s attempts at isolating a God gene were not about proving or disproving the existence of a higher power. They were about forming a clearer picture of what makes us human. This powerful, enduring feeling of spirituality — was it something we learned as we grew up and grew out of our primitive beginnings? Or was it something that’s always been with us since the start, a kernel of angelic light coded into our very beings?