Key Takeaways:

Kenzaburō Ōe was a literary giant who criticised factors damaging democracy and human rights in Japan, including nationalistic governmental policies, atomic power plants, and the imperial system. His early work explored the relationship between disenfranchised individuals and authoritarian power. Ōe’s “ambiguity” in Japan was a response to Kawabata’s “beautiful” representation, highlighting the multiplicity of humanity. Ōe’s work explored the multiplicity of Japanese identity and explored possibilities of healing through rigorous descriptions of all sides of human nature.

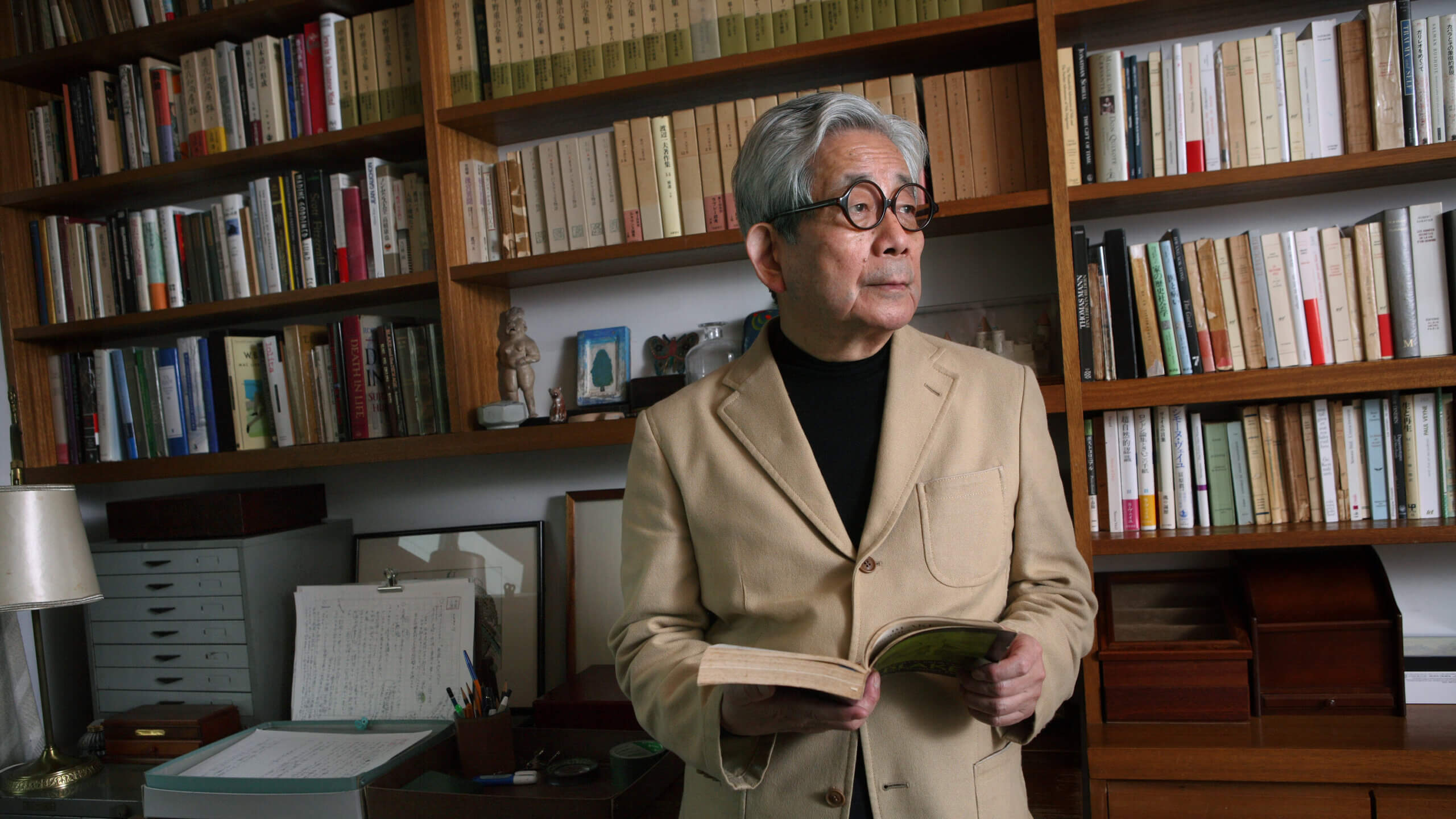

The death at 88 of Japanese writer and Nobel prize winner Kenzaburō Ōe on March 3 leaves a deep wound in his readers. But also in the Japanese community, which has lost one of its most powerful voices and critics.

Ōe was a literary giant. In Japan open political discussion and participation is discouraged and the media is often influenced by the government. Ōe was the last politically engaged Japanese postwar writer.

In his sharp, often merciless, commentaries of his country, he criticised factors damaging democracy and human rights, including nationalistic governmental policies, the presence of dangerous atomic power plants and the imperial system.

He even refused the award of the national Order of Culture, an honour bestowed by the emperor. Due to his open democratic commitment, he faced violent threats from right-wing organisations and was even brought to trial.

On and off the page, he combined an attentive focus on Japan with a profound knowledge of Western thought and expression, ranging from French philosophy (he graduated with a thesis on Sartre) to modern and classical authors such as TS Eliot and Dante Alighieri. This made him one of the few Japanese intellectuals whose work resonated with global questions of identity, injustice, and the search for home.

Bravely depicting postwar Japan

Born in 1935, Ōe started publishing in his twenties. His early work explored the relationship between disenfranchised individuals and authoritarian power.

In his first short story An Odd Job (1957) students are hired to help slaughter 150 dogs used by the faculty of medicine for experiments. The students’ predicament, ominously resembling that of the animals, speaks to his own postwar youth.

Japan in the 1950s was bereft of strong ethical and political models after the defeat of its nationalistic collective ideology in the Pacific war and the subsequent American occupation. Left without a definite identity and purpose, like Ōe’s generation, the youths in the story are at the mercy of an absurd system where they do not feel represented.

Ōe’s story Seventeen (1961) can be read as an extreme consequence of his first. The disenfranchised youngster here finds solace in abandoning his individuality to the intoxicating violent practices of a burgeoning imperialist nationalistic group.

Ōe’s career was shaped by his reflections on Japan’s incapacity (and unwillingness) to confront itself, acknowledge its war crimes and identify its position in Asia.

Upon being awarded the Nobel Prize in 1994, he spoke of “ambiguity” in Japan as a “chronic disease that has been prevalent throughout the modern age”. In his lecture, he referenced another Nobel speech by Yasunari Kawabata, the only Japanese writer to win the prize before him in 1968, entitled Japan, the Beautiful and Myself. Ōe’s was titled: Japan, The Ambiguous, and Myself.

By using the term “ambiguous” in response to the “beautiful” in Kawabata’s speech, Ōe placed himself in the history of global Japanese literature by distancing his work from the aesthetic representation of Japan that had dominated its cultural image abroad. This representation was of a country made of Zen Buddhism, tea ceremonies and a placid appreciation of transient beauty(among others).

The multiplicity of humanity

As well as presenting the country as he honestly saw it, he also foregrounds ambiguous and silenced Japanese identities.

Prize Stock (1958), which earned him the coveted Akutagawa Prize, launched him into literary prominence. This story depicts the encounter between a Japanese boy and a black prisoner of war in his island village.

In Japan, urban dwellers could discriminate against those from a rural background – a background that Ōe possessed growing up in Shikoku, the southern and smallest peripheral island in the main archipelago. In this story, the townspeople treat the villagers “like dirty animals” and in turn, the villagers refer to the black prisoner in the same way. Prize Stock is a discomfiting story about abuses of power and how everyone is capable of it.

Such exploration of the multiplicity of Japanese identity continued intersecting with reflections on space in his work.

The Silent Cry (1967) and Death by Water (2009) intertwine the stories of marginalised communities with folklore and tales of their ancestors’ uprising against local authorities. These novels highlight peripheral Japanese heritage and memories. They are also indicative of how the rural is never a simplistic idyll countering the suffocating corruption of the city in Ōe’s work. Instead, the rural is an organic alternative still replete with violence and discrimination, so nonetheless vibrant and real.

In Ōe’s work, the rigorous descriptions of all sides of human nature – light and dark, grotesque and cruel – offer possible reconciliation between seemingly opposing factors. Ōe saw his literature as a humanistic endeavour to represent human suffering and explore possibilities of healing.

In his commitment to writing honestly, he never shied away from his personal crises. He wrote often about the birth of his mentally disabled son Hikari, which generated the novel A Personal Matter (1964) and many others.

The acceptance of the coexistence of life with fatality inspired his subsequent essay collection Hiroshima Notes (1965), where he reflects on the political instrumentalisation of atomic bomb victims and underscores the need to respect their right to silence. His condition as a struggling father intersects with the meditation on those affected by man-made disasters in the atomic age, where annihilation can come suddenly. For Ōe, notwithstanding the scale, it was always a personal matter.

Now Ōe has probably “gone up” to the trees of his beloved native forest, to which, legends say, souls return after leaving the bodies. For us that remain, his memory will hopefully motivate a (re)discovery of his imaginative yet real portrayals of Japan and life, so powerful because they were so unapologetically human.