The title of this post is one of my absolute favorite quotes from Humans of New York, after the photographer questioned an interactive designer about how she created playful user experiences.

I think it perfectly explains the process we go through when designing products. Whether we’re doing something original or simply trying to understand (and maybe even question) the established best practices, we have to be wrong. Going down the wrong path is painful once you realize it’s a dead end, but the more we do it, the better we end up understanding the space and the better the end result becomes.

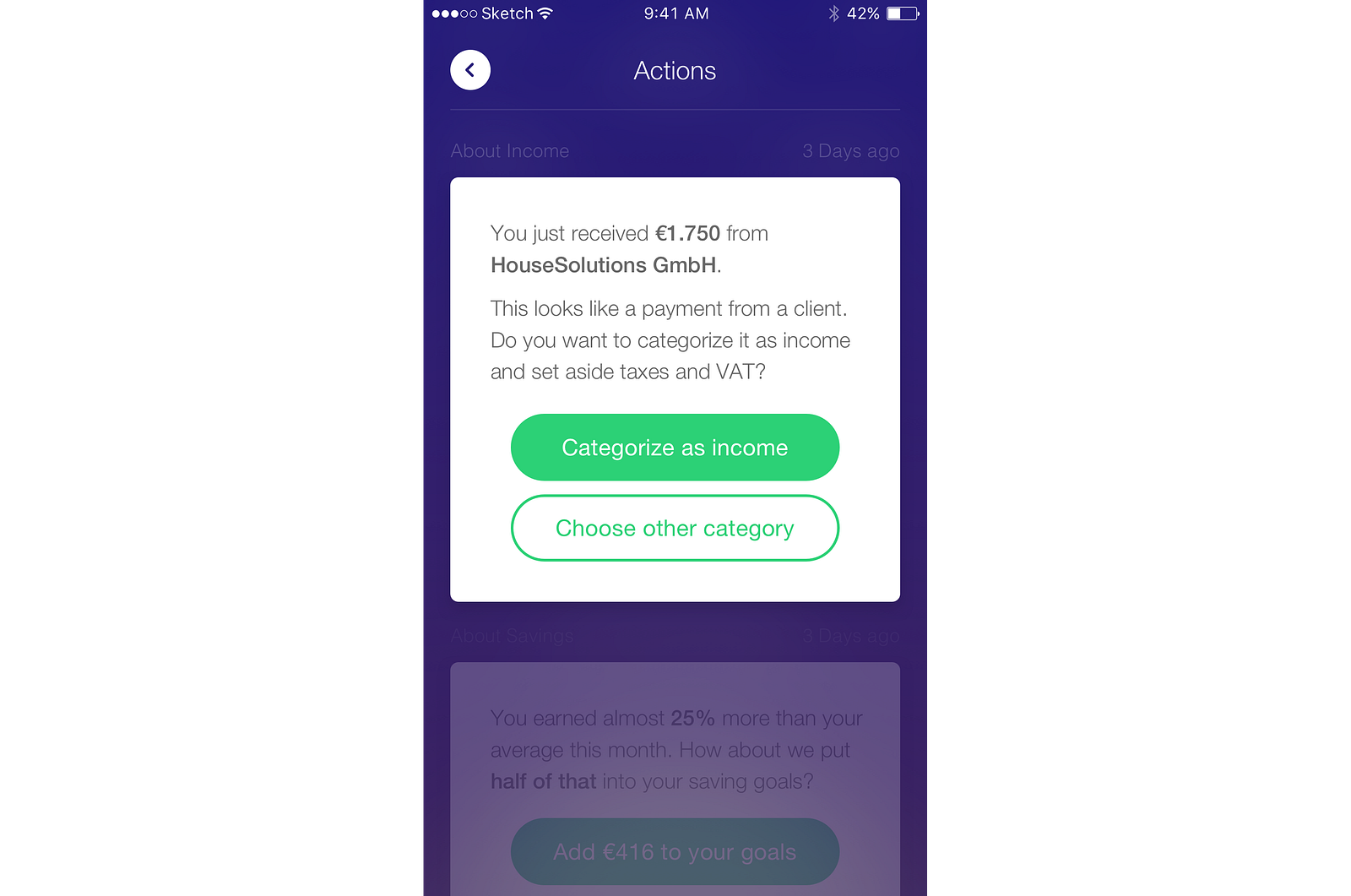

We’re currently building a bank for freelancers at Founders, and we’re calling it Kontist. During this process I was reminded of this quote again and of why it’s important for the process to be painful from time to time.

Theory: Set aside time to make no progress.

John Cleese gave a fantastic talk about what makes creative people. I really think you should watch it in its entirety, but the main point relevant to this post is that we operate in two different modes.

The open mode.

In the open mode we’re able to be creative — we have to put away the fear of being wrong and failing in order to play with original ideas. It is a place where curiosity for its own sake must be able to take place.

This mode isn’t just something that we can tap into whenever it’s needed, though. For it to exist, we need to create space for it deliberately, and we do this by setting fixed time slots where there is no expectation to make progress but simply to explore the subject.

MacKinnon’s research — the guy John Cleese referring to in the video — showed that the most creative people, are the people who stick with the problem longer. It’s that simple. The people who could endure the uncertainty of not having decided on a solution to the problem the longest came up with more original ideas.

As creatives, we have to learn to appreciate this uncertainty since every single failure might be a stepping stone to the next great thing. Even when we have to go back, as uncomfortable as it might be, we end up with a wider perspective of the environment we’re designing for and, in the end, a more creative conclusion.

The closed mode.

Once we reach a conclusion, we need to shift gears and go into the closed mode. This is a mode where we can confidently create and act upon a plan and decisively execute it without questioning its basis. Just like the open mode, switching to the closed mode must be a conscious decision, that is not something we can trust will occur naturally over time. If we were to try and let it happen by itself, we would always be pressuring ourselves into only moving forward, a pressure that would kill the foundation of the open mode and probably result in us taking the paved path and ending up with nothing more than another take on an already established concept.

The ironic thing about this urgency and fear of failure is that most of us within the startup community in one way or another are working with investors whose entire model is based on a “1 out of 10 success” mindset. They have truly accepted this mentality of failure as part of their business.

TL;DR

- Set aside time for the open mode, where no progress needs to be made but exploration can happen for the sake of exploration.

- Set aside time for the closed mode to plan and execute based on the learnings from the exploration.

- These two modes cannot exist at the same time and will not start or end organically.

This is, as with all good ideas, easier said than done, but we’re striving to make it part of our DNA at both Founders and Kontist.

Practice: Asking the painful questions.

This theory has come into practice over the past nine months during which we have been building financial services for freelancers. From countless hours of interviews with photographers, designers, developers, and the like, we’ve discovered that there is a huge disconnect between wanting to work freelance and wanting to “run a business” in a more traditional sense.

Knowing that a key part of the pain came from the financial and regulatory part of running a business, we took a deep dive into the financial tools and services that our interviewees used along with anything we imagined could solve some of the challenges we had seen. While going through the concept development process, we learned two lessons. One about the importance of time boxing the open mode, and secondly something larger about the kind of company culture that we need to build in order to survive.

Lesson #1 — Create hard time boxes for the open mode.

We started experimenting with different concepts that could automate parts of the process where we had identified problems worth solving. We ended up with everything from instant invoice payments and calculating taxes to freelancer storefronts.

Looking back, there are plenty of concepts that we still have a lot of faith in. As good as this might sound, it’s also begs the question: Why didn’t we just pick one of the earlier ones instead of beating around the bush and coming up with even more concepts? The answer is the fear of the uncertainty that is bound to be a big part of any orignial idea.

Because we hadn’t defined a fixed time box for the open mode, we ended up trying to compare our concepts with the next great thing that might be lurking around the corner, a comparison from which it is impossible to deduct any conclusions.

Going forward, we need to time box the open mode so that when we need to make a decision, we have a defined amount information to base it on.

Lesson #2 — Build a culture of seeking out the painful process.

We fell in love with the thought of making it as easy being self-employed as it is being an employee. But a few things dawned us as we continued our interview sessions around freelancers’ finances:

- People really don’t want to be bothered about this field except on an I-want-to-stay-out-of-trouble-with-the-authorities level.

- People interact with their finances through their bank, and add-on services simply add another layer people have to interact with before needing to go to their bank to manage it manually according to these services.

Based on this, we knew we would need to replace the existing banks they used for their businesses.

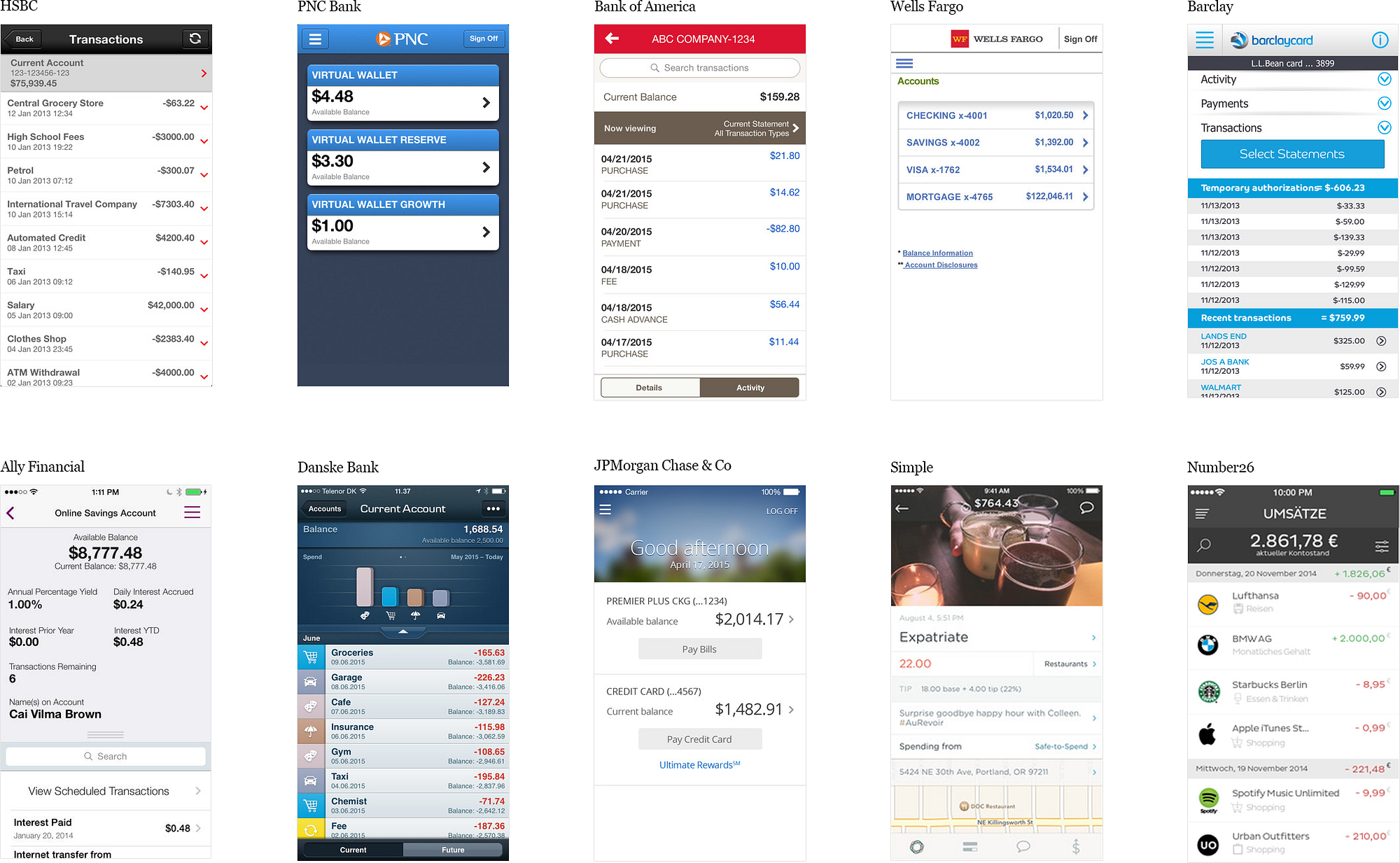

Going through the different offerings, it quickly became apparent that we had 50 different interpretations of how a ledger could look in 2016. These included automatically categorizing transactions, displaying financial history with fancy graphs, or even trying to predict the future a bit. But at the end of the day, we were still looking at systems with a ledger as the epicenter, and lists of transactions.

We’ve come to the conclusion that a bank is nothing more than a building with a ledger. This is not our focal point. Taking a step back, we get the customer using money as a tool to do something, and from that point we can begin to examine their needs and what drives them. It sounds ridiculously simple, but when building these mechanics it’s easy to get caught up in fixing the system rather than peoples actual problems.

Right now there are tons of problems, depending on whom you ask. Our demographic is severely underserved and so far we’ve gotten pretty good indicators of what we need to do. But in short, our epicenter is behavior and not a ledger for keeping track of transactions.

All in all, we’re turning the core of the traditional banking business upside down.

Full disclosure, rethinking the core business is easy. In Founders and Kontist, we haven’t built a banking business (yet), and nobody around the office is going to be made redundant if we decide to pivot tomorrow. Nothing is sacred and the bar for what’s outrageous is pretty high. But going forward we need to maintain and foster a culture that allows for this continuously, as well as always be willing to take a step back into the uncertainty of the open mode.

We cannot expect this process to come naturally since it’s in our nature to shy away from painful things. But if we don’t, somebody with nothing to lose will come in and ask the painful questions for us.

TL;DR

- Acknowledge and accept uncertainty when transitioning into the closed mode. More time can always be used to explore and learn, but we must go forward relentlessly, knowing that the next time we enter the open open mode we’re going to be more knowledgeable than ever based on our experiences executing.

- Create a culture of seeking out the painful process or fall behind those who dare.

About the Author

This submitted article was written by Rasmus Landgreen.