Key Takeaway:

A study has found that people who distrust science are not only not well-informed about the facts but also believe they do understand the science. This distrust is not just due to a deficit of knowledge, but also a lack of trust in the message and messenger. Research has shown that people who reject or distrust science are not particularly well-informed about it but typically believe they do understand the science. Overconfident people who dislike science often have a misguided belief that their viewpoint is the common viewpoint and many others agree with them. To address this, it is suggested that the messenger is just as important as the message. A complementary approach is to prepare people for the possibility of misinformation and emphasize uncertainty in fast-changing fields.

For many years, it was thought that the main reason some people reject science was a simple deficit of knowledge and a mooted fear of the unknown. Consistent with this, many surveysreported that attitudes to science are more positive among those people who know more of the textbook science.

But if that were indeed the core problem, the remedy would be simple: inform people about the facts. This strategy, which dominated science communication through much of the later part of the 20th century, has, however, failed at multiple levels.

In controlled experiments, giving people scientific information was found not to change attitudes.

The failure of the information led strategy may be down to people discounting or avoiding information if it contradicts their beliefs – also known as confirmation bias. However, a second problem is that some trust neither the message nor the messenger. This means that a distrust in science isn’t necessarily just down to a deficit of knowledge, but a deficit of trust.

With this in mind, many research teams including ours decided to find out why some people do and some people don’t trust science. One strong predictor for people distrusting science during the pandemic stood out: being distrusting of science in the first place.

Understanding distrust

Recent evidence has revealed that people who reject or distrust science are not especially well informed about it, but more importantly, they typically believe that they do understand the science.

This result has, over the past five years, been found over and over in studies investigating attitudes to a plethora of scientific issues, including vaccines and GM foods. It also holds, we discovered, even when no specific technology is asked about. However, they may not apply to certain politicised sciences, such as climate change.

Recent work also found that overconfident people who dislike science tend to have a misguided belief that theirs is the common viewpoint and hence that many others agree with them.

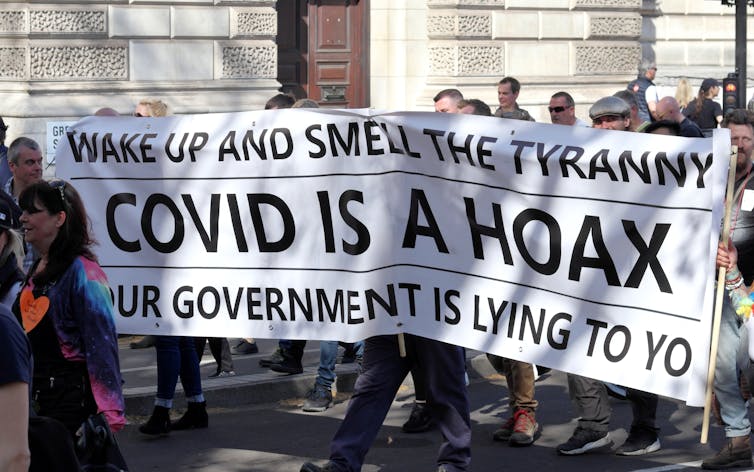

Other evidence suggests that some of those who reject science also gain psychological satisfaction by framing their alternative explanations in a manner that can’t be disproven. Such is often the nature of conspiracy theories – be it microchips in vaccines or COVID being caused by 5G radiation.

But the whole point of science is to examine and test theories that can be proven wrong – theories scientists call falsifiable. Conspiracy theorists, on the other hand, often reject information that doesn’t align with their preferred explanation by, as a last resort, questioning instead the motives of the messenger.

When a person who trusts the scientific method debates with someone who doesn’t, they are essentially playing by different rules of engagement. This means it is hard to convince sceptics that they might be wrong.

Finding solutions

So what we can one do with this new understanding of attitudes to science?

The messenger is every bit as important as the message. Our work confirms many prior surveys showing that politicians, for example, aren’t trusted to communicate science, whereas university professors are. This should be kept in mind.

The fact that some people hold negative attitudes reinforced by a misguided belief that many others agree with them suggests a further potential strategy: tell people what the consensus position is. The advertising industry got there first. Statements such as “eight out ten cat owners say their pet prefers this brand of cat food” are popular.

A recent meta-analysis of 43 studies investigating this strategy (these were “randomised control trials” – the gold standard in scientific testing) found support for this approach to alter belief in scientific facts. In specifying the consensus position, it implicitly clarifies what is misinformation or unsupported ideas, meaning it would also address the problem that half of peopledon’t know what is true owing to circulation of conflicting evidence.

A complementary approach is to prepare people for the possibility of misinformation. Misinformation spreads fast and, unfortunately, each attempt to debunk it acts to bring the misinformation more into view. Scientists call this the “continued influence effect”. Genies never get put back into bottles. Better is to anticipate objections, or inoculate peopleagainst the strategies used to promote misinformation. This is called “prebunking”, as opposed to debunking.

Different strategies may be needed in different contexts, though. Whether the science in question is established with a consensus among experts, such as climate change, or cutting edge new research into the unknown, such as for a completely new virus, matters. For the latter, explaining what we know, what we don’t know and what we are doing – and emphasising that results are provisional – is a good way to go.

By emphasising uncertainty in fast changing fields we can prebunk the objection that a sender of a message cannot be trusted as they said one thing one day and something else later.

But no strategy is likely to be 100% effective. We found that even with widely debated PCR tests for COVID, 30% of the public said they hadn’t heard of PCR.

A common quandary for much science communication may in fact be that it appeals to those already engaged with science. Which may be why you read this.

That said, the new science of communication suggests it is certainly worth trying to reach out to those who are disengaged.