Brave New World. The Matrix. The Truman Show. Inception. Source Code. And the latest dystopia I’ve seen: Archive. They all trade on the same group of basic structures: the idea that we do not exist, and moreover, may never have; that we are but algorithms; that we are mere vestiges of something past; or that reality is anything but real, in spite of the perception that our qualia tell us it must all be real because we are seeing and feeling it; and equally because we are incapable of accepting the alternative — of facing the truth about our own non-existence.

The concept of solipsism — that one’s own mind is the only thing for sure that we can know to exist, and that other minds, and the external world itself, may not exist at all, beyond its psychological fabrication — is perhaps the most consequential idea in the history of ideas.

It’s the one more than any other idea that has gripped several of history’s most brilliant minds, including Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, Rene Descartes and the ancient Greek Gorgias, who first proposed it, millennia ago.

The core issue is: one cannot prove it out.

Yet.

The Origins of Nothing

Gorgias stated the following:

“Nothing exists. Even if something exists, nothing can be known about it. Even if something could be known about it, knowledge about it cannot be communicated to others,” in the sense that “objective knowledge” is an impossibility.

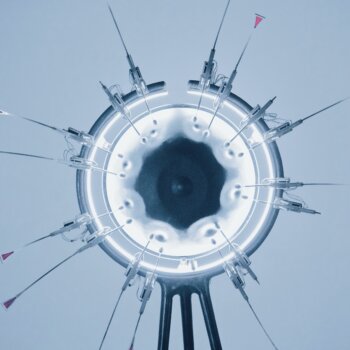

Nick Bostrom published his “simulation argument” back in 2003. Here is a video in which the Swedish philosopher and founder of the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University explains what he sees are the only three possibilities about who — or what — we are, and that only one of these can be true.

His “trilemma” is as follows:

1. “The fraction of human-level civilizations that reach a posthuman stage (that is, one capable of running high-fidelity ancestor simulations) is very close to zero”, or

2. “The fraction of posthuman civilizations that are interested in running simulations of their evolutionary history, or variations thereof, is very close to zero”, or

3. “The fraction of all people with our kind of experiences that are living in a simulation is very close to one.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson, the astrophysicist who runs the Hayden Planetarium in NYC and hosts Cosmos, is — like Musk and Hawking — convinced we do not exist, and are merely simulations. They’re not alone. Scientific American put it at a 50–50 chance in an article last year. Vox jumped in, adding, “I don’t know. Probably.” Vulture cites “15 irrefutable reasons” for its veracity. And Code Conference attendees got to hear Musk himself say that “the odds that we’re in ‘base reality’ is one in billions.”

Back to deGrasse Tyson. His 2016 Isaac Asimov Memorial Debate went down that rabbit hole. You can watch it here, if you have two hours to spare. In it, David Chalmers, Max Tegmark, James Gates, Lisa Randall and Zohreh Davoudi do what all theoretical physicists, philosophers and mathematicians do: they geek out, in great detail and depth, leaving the rest of us gawking, or utterly confused.

At one point in the video, deGrasse Tyson grounds everyone when he explains the order of the universe: “Everything is mathematics. And if everything is mathematics, then everything is programmable.” Which includes us.

There are few serious minds alive today that would disagree with his statement.

Four hundred years ago, Galileo — aka the father of modern physics, the scientific method, and modern science, as he is inevitably called — wrote, “The Universe is a grand book written in the language of mathematics.”

It is only we who cannot — will not — entertain what minds greater than ours have concluded: that we are best solipsists, alone in the world, and manifesting a universe in our minds in order to feel less lonely, and from which we hope to derive purpose; and that at worst (or best, if that’s your jam) we are living in a simulation, here but for the present pleasure of our descendants, or forgotten by them long ago yet still running, by mistake, in some corner of a future attic or basement, like that Jumanji console.

Why does any of this matter? Why waste time thinking about it, when nothing can be done, anyhow, about whatever truly is?

Religious Reconciliation

It matters because we are at the very least under the impression that we exist, and that we spend somewhere up to 100 or so years on a little blue marble… for a reason. And so, it matters because what we do while alive is either filled with hubris — ego — or with empathy-fueled humility. Which of these drives our actions depends, pretty fundamentally, on whether we believe we are alone in the world or part of a larger community of humans and other living creatures.

Let’s say we believe we do exist. Most humans on Earth still believe in the most successful story ever hatched by a human mind. It takes many forms, and defending that story has led to more deaths — at hundreds of millions — than anything else we have chosen to believe in. We call it religion, and the nut of religion is that a god, or a cabal of gods, made us in its/their image(s).

Hmm. How does that NOT sound more than a little bit like Bostrom’s theory about some future, technologically omnipotent descendant electing to create us in its image? He simply stops shy of positing that it programmed us to adore and worship it, wage war to advance belief in it, or protect the belief that because it created us, we should spend our entire simulated lives in service of our programmer, flogging ourselves for falling from its perfect grace.

And so: if you believe in religion in the literal way — that we were created in the image of an omniscient being — then it’s not a stretch for you to accept that in fact we may be simulations of the ancestral form of that being, because something must have created it, too, which must be some form of our common ancestors.

In fact, if a god or more exists, then, it might be the greatest supporting argument for Bostrom’s and others’ theories.

I’d bet on it.

The Ghost, With or Without a Machine

The other grand benefit of believing in Simulation Theory, as it’s now called, is that it proves definitively that all of the things we twist ourselves into a knot about in life — grades, norms, fitting in, position and power, legacy, death — don’t matter, because they’re not real; and therefore the things that cause us the most stress and anxiety in life, around which we galvanize the majority of our existential energies, have no basis of justification.

This, my friends, is a very freeing concept.

Being “free” — of the rat race, of expectations from self or from others, of keeping up with the Joneses, of approval-seeking, of “in” status — is about as empowering as anything I know.

All that remains, then, if we do not in fact exist, is to make choices based on something more intrinsically self-determinate, whether or not it is simulated. Because until the lights go out, we are running the show (or at least think we are); so we may as well enjoy the game we are playing, because there’s no alternative anyhow.

Descartes’s concept of “dualism” — that the mind is not physical, and exists independent of the brain — stops short of explaining what this mind is. That is, whether it is a simulation, or something more spectral. The expression ‘Ghost in the Machine’ was coined in 1949 as a slight — a rebuttal — to Descartes’ thinking. Today, computer programmers have appropriated the term to describe what happens when a program runs contrary to their expectations.

In other words, when it acts not predictably, but erratically.

Like a human.

Perhaps we humans ourselves, then, are the ghosts in the machine. Perhaps we are the illogical, erratic source code errors, or viruses, standing in the way of mathematical purity.

Why not? After belief in religion, our belief in ghosts — ancestors or otherwise — is the next most popular human story. Every society in the history of societies has some form or another of belief in ghosts. It’s easy, then, to imagine some future post-human version of ourselves referring to us as ghosts in the machine, and we have somehow picked this notion up as a form of solipsistic belief.

In spite of our programmers.

Belief Beats Reality, Every Time

What matters more? The belief that something is true? Or empirical truth, whether or not it conforms with our pre-existing notions? Well, I’d argue pretty heavily that beliefs are the only things that drive our actions. As most of us know, these beliefs stem from our perceptions of the world, which include subjective beliefs about what it is; how to navigate it; what matters, and why; and our identity within the complexity of a single human mind, a society, and the cosmos.

Put bluntly, if we don’t believe it, it doesn’t exist — at least not for us. How often do we wring our hands about — or even consider — something we don’t believe in, or believe matters? Things that are so far away from us emotionally that we readily purge them from our thoughts and lives, such as all the people on the planet being oppressed, or killed, or overlooked, or punished, or dying from something “we don’t have here”?

I’ll tell you. For most of us, it’s zero.

And so, what we believe — and what we believe impacts us and ours — drives everything about us.

Do all beliefs stem from empirical, epistemic observation of the world? Or are they simply narrative, non-transferrable interpretations of stimuli? Here again, there’s no argument to be had, by any serious person, favoring the former.

Truth is relative.

I wrote this piece on the subject last year.

We are meaning-making machines; narrative yarn-spinners, good and bad. Nothing exists but for what we make of it. When two or more people experience the same phenomenon, they invariably come away with very different interpretations of it, at least below the surface, once internalized. Now multiply that over a lifetime of phenomena and perceptions, mathematically compounded, and interpreted.

We are impossibly complex stories — nothing more.

So, why are we so rooted to the idea of being “right”? Of “reality”? Of “rational thought”, which to me sounds like an oxymoron, if in fact nothing exists but our narrative perceptions? Maxwell Maltz’s foundational book Psycho-Cybernetics, from which I’ve quoted liberally, and about which I’ve written at length, dives deep into why we make meaning of the narratives we choose, and offers ways out from the strictures of crippling narratives onto which too many of us hold. Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning is no different: he posits that our perceptions are ours alone to determine, and Frankl, on his deathbed in Auschwitz, credits this alone with his survival, and phoenix-like emergence. Mo Gaudet’s Solve for Happy is yet another one — one that allowed him to emotionally survive the death of his son. Carol Dweck’s seminal Mindset? Yet again here, she helped a generation (or three) understand that our minds alone empower or disempower everything we do; and that there are practices we can engage in to come out on the upside of this dyad.

Waking life isn’t the only state from which we humans derive meaning. Dreams are another; meditation a third; and psychedelic experiences a fourth. There are others. The point of bringing them up here is to say that anyone who is experienced in any of these things will account for how transformational they can be on our thinking, including our perceptions of our place in the world, and our ensuing actions.

Bad dreams can ruin a day, or a week, even though “we know they aren’t real”. Our emotional states drive everything; and when we are unsettled or ebullient, our resulting frames of mind influence us deeply.

Advanced meditators will invariably tell you that their practice has transformed them. Equally invariable is their belief that they have become better people as a result, with increases in patience; connectedness; inner peace; centeredness. These are common outcomes of the practice, at a deep enough level of committed engagement. And yet: what exactly transpired to feed these perceptions? Certainly nothing as ‘real’ as getting hit by a stray pitch, a car or a bullet?

Or do we utterly misunderstand the term “reality”, choosing to see it in physiological terms, rather than emotional ones? The ‘ghosts’?

It’s not only meditators whose visions transform them. Psychedelic therapies — both medically and shamanistically administered — are re-emerging, thankfully, after a 50-year witch hunt by nervous politicians who feared they would lose control over citizens empowered by these magic molecules. The facts underlying the hype speak to a very different story.

Soldiers suffering from PTSD; manic depressives; suicidal teens, and adults; all of these groups have benefitted measurably, empirically, from psychedelic ‘trips’. Our fMRI machines tell us so, corroborating the anecdotal experiences of the humans that take them, and are healed. In fact, these are the singularly most effective therapies humans have either derived or discovered — ever. Michael Pollan’s excellent book How to Change Your Mind covers this extensively, as does Jamie Wheal and Steven Kotler’s Stealing Fire.

It’s not only those with clinical maladies who have benefitted. One reason psychedelic substances are so broadly attractive — the way meditation is — is that there is something fundamentally restorative to the experiences they reveal to us — to our psychic health and interpersonal wellbeing. They are, put another way, as real as real gets!

All of this points to the idea that belief is reality — at least as much as the physical world in a waking state is reality, and in many cases (if not all), more so.

Final Thoughts

To revisit my earlier question, does it matter whether or not we exist as empirical beings, if we feel we do in any event, and when feeling is the most real thing we have?

Of course it does.

Altered states induced by meditation, dreams and psychedelics certainly make us feel powerful things, but these — at least as much as experiences had in wakeful states — are there to manifest positive impacts on lives that we believe to be the modus operandi of our existence. For insights about what to do while we are (potentially) here on Earth, as brief as that may be.

The moment we consider that none of this may be real, and that we either serve a god, old-school, or a coder or AI engine, new-school, then the urgency with which we approach life — urgency that more often than not translates to intra- and inter-destructive behaviors fueled by raised levels of cortisol — the stress hormone — goes away, allowing us relief from the pressures that attend most lives and color our decision-making capacities, often for the worse.

In other words, if none of this matters, then we are free. And freedom from the prison of our minds manifests as a preternatural calm, connectedness and wellbeing. It is, at the very least, a beautiful, even optimal, state of mind to have.

I just binge-watched the one-season series Brave New World, which led to this musing. I’ve no idea why they cancelled it, but presumably it didn’t catch people’s fancy enough to warrant the time and expense. That’s sad. The show’s power came in the form of the protagonists’ dawning realization that an AI created by ten “world controllers” (the series was inspired, if not based, on Aldous Huxley’s seminal novel — a novel that emerged from a mescaline trip he had just taken!), has completely and utterly taken over the citizens of New London’s perceptual lives. The series stops short of calling all of life a simulation, but it got me thinking about it, nonetheless.

As AI becomes increasingly powerful; as genomics and mathematics uncover the biological signatures of human beings and the universe; and because the rate of development for these things remains dizzyingly exponential; it is only a matter of time before what makes us human — apart, perhaps, from our Cartesian ‘ghosts’ — is reduced to an algorithm. This is the central focus of new science, and we are marching headlong into the mire. At some point in the near future (by which I mean the next several generations, if not only a handful of years), we may be able to upload our cortexes to a cloud, the way Ray Kurtzweil believes will happen within the next decade. He’s rarely been wrong about anything, thus far. If that happens, or if we allow human beings to simply dial emotional states with substances, we will surely be altering what we believe it has meant to be human, for all of history. Perhaps, like Neo, a few of us will be able to see the source code. Some psychonauts believe this is, in fact, what underpins their powerful feelings of peace: within, with humanity, with the planet, and with their own demise.

The term ‘ego death’ is one often cited by people who have ingested some of nature’s strongest psycho-stimulants. This refers to the complete dissolution of the ego — the self — as something separate from everything else. Ego death’s result is the feeling of intrinsic oneness with everything and everyone. This is the apex state of human emotional reach, and what can take a monk 40 years to do can also be the outcome of a ten-minute DMT trip.

Just ask Pollan.

Whether we are flesh-and-blood beings as part of a terrestrial ecosystem capable of finding magic, or lines of mathematical code programmed by our future self-gods playing a lifelong adventure along the lines of Roblox, Avatar or Ready Player One, I have the same takeaway:

What is so bad about that?