Key Takeaways:

- This is what Gandhi meant by “We need not wait to see what others do,” because we are world-makers in our own right: worlds that don’t empirically exist outside of our minds, except in the actions they sponsor.

- People are especially likely to process information to support their own beliefs when the issue is highly important or self-relevant.”

- And Genova is illustrating that without adequate investment in an awareness-fueled system of internal checks and balances, we all become caricatures of ourselves over time, insofar as the grooves of our memories (and the hyper-selective perceptions they feed) only deepen.

- We can—and many of us do—perseverate over fights, building an arsenal of negative memories and justifications for why we were right and why they were wrong, thus pulling our experiences ever farther from the realm of “good memories”, while simultaneously deepening our risk of embitterment.

- And so, we come back to the initial Gandhi-esque exhortation: “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

I began my last piece on memory—Bliss is in the Forgetting—with the quote “ignorance is bliss”. I should start this one with another:

“Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

Like Einstein, Gandhi gets a lot of credit for brilliant witticisms… that he never authored. With regard to the quote above, what Gandhi did say—in 1913—is as follows:

“We but mirror the world. All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. This is the divine mystery supreme. A wonderful thing it is and the source of our happiness. We need not wait to see what others do.”

The passage is beautiful. Just apparently not pithy enough for a meme.

What Gandhi was pointing out is that the world is a reflection of our internal state: not of facts, but of perceptions. In other words, if we see a hostile world we feel is out to get us, then that’s exactly what the world will represent to us, whether or not it is, in fact, hostile! Inversely, if all we see is the good—in people and in fortune—then that’s precisely the reality we will find.

This is what Gandhi meant by “We need not wait to see what others do,” because we are world-makers in our own right: worlds that don’t empirically exist outside of our minds, except in the actions they sponsor.

My mother has her own version of this. She has told me for as long as I can remember:

“If you look hard enough for something, you’ll eventually find it.”

While Gandhi is long gone, I have the luxury of engaging in discussion with my mother, which is why I know that her mantra refers to perception, not fact. If, in conversation, we are expecting someone to be mean, boring or arrogant, that is all we will be able to see in that person, because meanness is all we are looking for. In other words, they can be lovely 99% of the time, and callous 1% of the time, and all we will remember is the time they were callous.

It’s called confirmation bias, and we are all guilty of doing this.

Confirmation Bias

Brittanica—aka Wikipedia for the bygone era of shared truth—describesconfirmation bias as:

“the tendency to process information by looking for, or interpreting, information that is consistent with one’s existing beliefs. This biasedapproach to decision making is largely unintentional and often results in ignoring inconsistent information. Existing beliefs can include one’s expectations in a given situation and predictions about a particular outcome. People are especially likely to process information to support their own beliefs when the issue is highly important or self-relevant.”

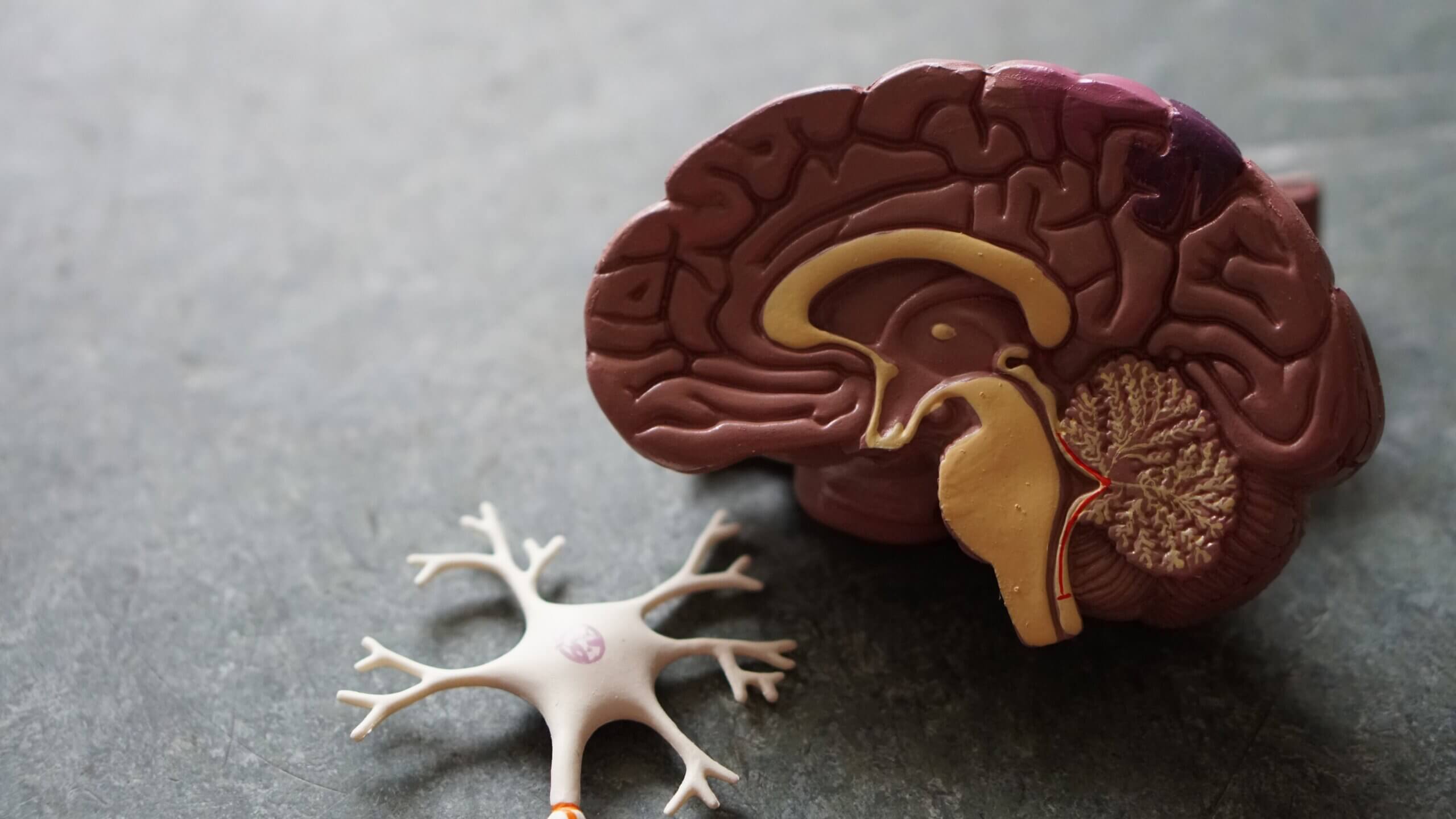

In other words, our memories are highly selective, omitting large chunks of information. Moreover, this universal phenomenon isn’t due to some form of faulty wiring in the human mind. Rather, it’s a willful outcome of selective attention and oversight.

And what drives our selective attention is our ego.

In her book Remember, author Lisa Genova writes:

“What you remember depends on the kind of life story you’re creating. We tend to save the memories that feed our identity and outlook.”

AKA: confirmation bias.

But here’s where it gets interesting, and the passage that inspired me to write this second piece on memory. Genova shares two anecdotes about people she knows personally, to illustrate how self-amplifying our confirmation biases can be.

“My friend Pat has the most positive attitude of anyone I know. I would bet that Pat’s autobiographical memory is populated with laughs, appreciation and awe. My great aunt Aggie, on the other hand, was a chronic complainer. Her life story—the meaningful memories she retained of what happened in her life—was a tale of woe.”

“Similarly, if you believe you’re smart, you’re more likely to remember the details of the times when you did something intelligent and you’re more likely to forget the times you made dumb mistakes. And by continuing to recall and reminisce about the stories that illustrate how brilliant you are, you reinforce the stability of those memories and who you believe yourself to be.”

In this way, the stories we tell ourselves become our realities, whether or not others see us through very different lenses.

If that doesn’t explain psychopaths and narcissists, I don’t know what does. They actually believe the vitriol they spew. It’s not fakery. In this way, at least they are honest brokers of (extreme) worldview.

The same can be said of the Dalai Lama, and other unshakeable optimists. We all know people who walk down the street glowing with an aura of calm, or joy, or openness. We equally all know people whose ‘vibe’ puts us off, making us want to steer clear of them, even if we have never heard them open their mouths.

Our perceptions are immensely powerful—none more than the perception of self. And Genova is illustrating that without adequate investment in an awareness-fueled system of internal checks and balances, we all become caricatures of ourselves over time, insofar as the grooves of our memories (and the hyper-selective perceptions they feed) only deepen.

I’m sure we can all picture parents, grandparents or other older individuals who somehow seem to become a more extreme version of themselves as the years pile up.

Now you know why.

Perseveration

One of the most interesting words my wife uses regularly (and I love words) is “perseverate”. In psychology-speak, to perseverate is “to repeat or prolong an action, thought, or utterance after the stimulus that prompted it has ceased.”

AKA: to “fixate”.

When we perseverate, we unwittingly shape our worldview, and by extension, our lives. That’s because we don’t even perceive the things we ignore, due to both confirmation bias and perseveration. As a result, that which reaches and is reinforced by our conscious minds becomes a half-truth of a subset of reality.

We are all guilty of this, because we are hardwired to be that way.

As my mother (also) always asks [she really is a very wise human]:

“Would you rather be right, or happy?”

The humor in her comment is exactly why this topic is so worthy of reflection. The world we live in is the one we have created, and that we continue to create, every single moment of every day, through the application and perseveration of hyper-selective memories.

Right, or Happy

The term “ignorance is bliss” aptly applies to any form of memory that diminishesour optimism, openness or love.

Feuds. Political scapegoating. Racism. Grudges. Competitiveness. None of these leads to a happy tomorrow. All of them drag the (perceived) world down with them.

One of my favorite sayings is, “Let go or be dragged.”

You know those social media algorithms that makes the left “lefter” and the right “righter”? They are taking the selectiveness to which we are already, biologically, predisposed (see: Gandhi, above), and hyper-amplifying it with algorithms designed to reduce inputs to those on which we already naturally perseverate!

What a recipe for disaster!

In the context of an always-on society whose own hyper-selectivity is amplified by cherry-picked inputs, it’s no wonder civilized debate is dead, dialectics is seen as an assault, violent anti-everything-that-isn’t-“my-truth” is skyrocketing, and sense-making is shattered.

But.

Final Thoughts

We are still in charge of this world, because the world in which each of us lives is no more than a product of our making.

So, unless you don’t believe in free will, that’s really, really good news.

As Genova pointed out, the more we revisit stories, the stronger those memories become. Our minds like jars: we can fill them with good things or bad. When we reach into those jars to pull out their contents, we strengthen the synaptic links between what we perceived and what we now remember.

Even when we do have a legitimately negative experience—say, an ugly fight with our spouse—we can still choose our reactions. In that circumstance, what matters most isn’t selective remembering, but willful forgetting.

We can—and many of us do—perseverate over fights, building an arsenal of negative memories and justifications for why we were right and why they were wrong, thus pulling our experiences ever farther from the realm of “good memories”, while simultaneously deepening our risk of embitterment.

Or.

We can actively determine not to hold onto those memories, thereby weakening rather than strengthening them, and in the process, allowing selective forgetting to create space within us to focus on building sympathy and forgiveness in lieu of grudges and resentment.

The difference is all in the memories we choose to amplify, vs. those we choose to forget.

And so, we come back to the initial Gandhi-esque exhortation: “Be the change you wish to see in the world.” In the paradigm of ‘being change’, we are the sum of the things we choose to remember and forget.

It’s not rocket science, but the best path to happiness is… be happy! Like attracts like. Happiness begets more of the same: in our hyper-selective focus, in the perceptions that it creates, and in the memories we are more likely to replay and strengthen because we gave precedence to them, while actively forgetting others, for no other reason than because they didn’t help us get to the place of our dreams.

Equanimity.

Choose your memories wisely.