John Maynard Keynes first introduced the idea of technological unemployment in the 1930s. By it, he meant job loss from technological innovation. It remains a controversial topic today. That’s because some people believe technology unleashes more new jobs than it destroys, while others don’t.

One of the reasons for this disagreement is that we don’t always fully recognize new forms of work. Before the industrial revolution, work meant a day in the fields. Then manufacturing took over and it was probably hard to imagine that it would one day be replaced by services. We face a similar crossroads today. The future of work surrounds us at every turn. We just don’t yet recognize it as such.

When people talk about technological unemployment, what they’re really talking about is automation. Automation transforms work in ways that reduce or eliminate human labor. In practice, automation never really eliminates all human work. By handing tasks to machines, we let go of some employees while making those who remain more productive in their work.

We’ve seen this game before. Automation dramatically shrunk employment in agriculture and manufacturing while simultaneously boosting output in these sectors of the economy. It’s happening again, but now in the services sector, which accounts for 80 percent of U.S. jobs and GDP. This time though, the process looks very different.

Automating Services with Ease of Use

There is a simple and fundamental difference between work in agriculture and manufacturing compared to work in the service sector. Farmers and factory workers create economic value through what is traditionally described as production. But whether it’s hotels, health clubs or hospitals, service workers primarily create value in concert with customers. There is no restaurant service without a diner and no ride share service without a rider.

What this means is that when service companies automate, technology replaces employees as the medium through which customers engage the company. Service automation thus enables end users to serve themselves with what can best be described as “automated self-service.”

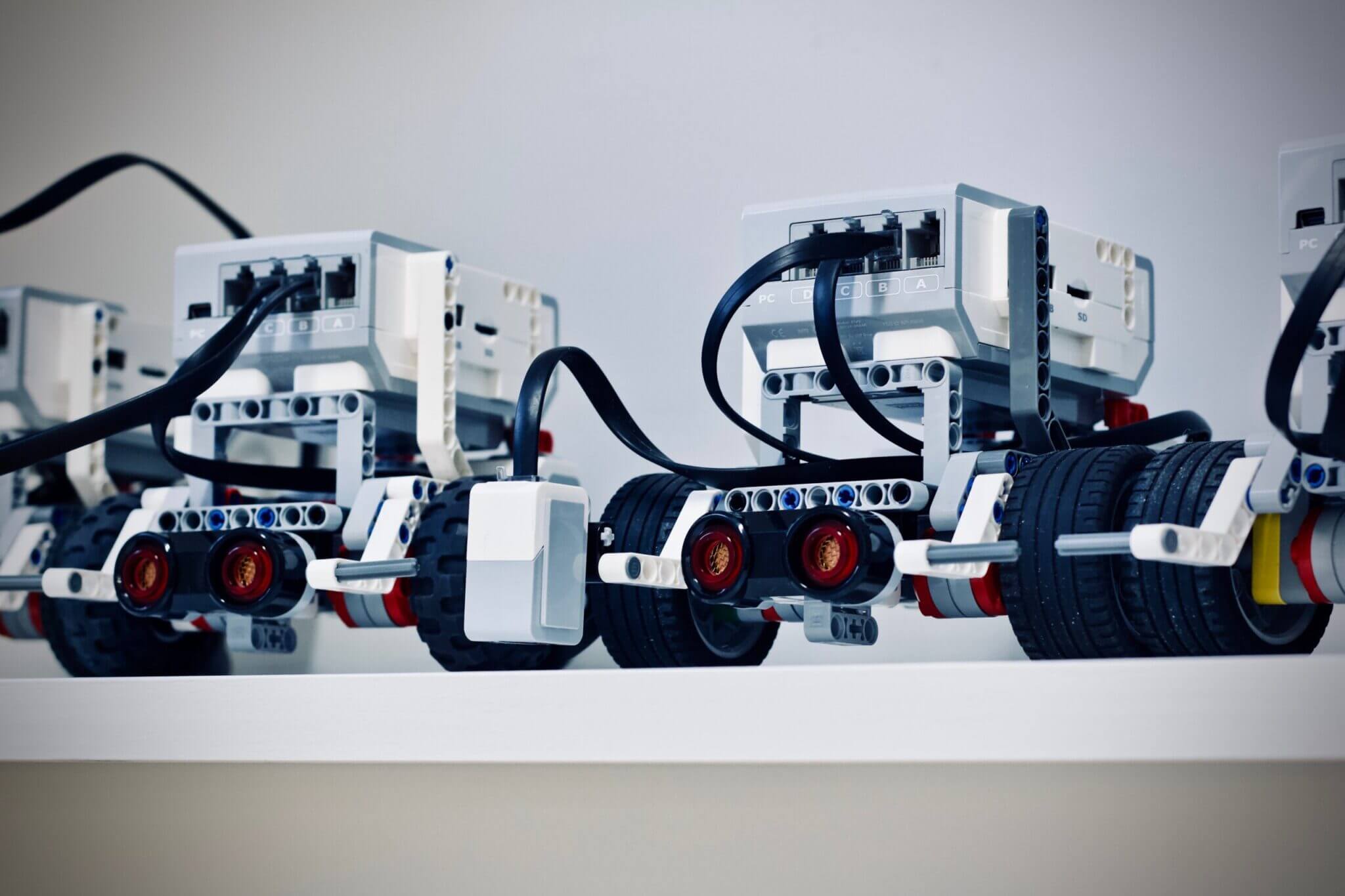

The hard thing about automation is its points of contact with humans. Early factory automation solved this by simply cordoning off workers from fast-moving robotic arms. When companies needed closer collaboration between robots and humans, it was cheaper to train well-qualified humans than to build easy-to-use robotic interfaces. But when it comes to automated self-service, these points of contact expand exponentially. The prospect of training millions of novice end users proves insurmountable, so the focus shifts to dramatically simplifying these interfaces so they are drop-dead simple to use.

The evolution of automated self-service is an interesting story that goes back a long time. By the 1980s, companies started to shift these interfaces from hardware into software. Over the course of the 1990s, the web took over as online giants like Amazon, Netflix and Google revolutionized their markets by allowing end users to serve themselves. These services used the data generated by their overwhelming “Internet-scale” to train machine learning systems. Using voice recognition and other AI tools, these companies one service after another by making automated self-service easier and ever more convenient to use. As their scale expands, so too does the resulting data flow and intelligence in an upward spiraling virtuous cycle.

End Users Become the Future of Work

To understand the full implications of automated self-service, we need to more closely investigate the work happening outside of formal employment agreements. That might include pumping gas or posting things on Facebook but also—less obviously—watching a movie or eating a meal in a restaurant. We don’t tend to recognize these activities as work for a number of reasons. For one, we don’t get paid for them. But then again we don’t get paid for yard work, housework or community work and still consider these activities a form of work. I think the bigger reason we don’t consider these activities work is that we get utility from them and that many of them are downright enjoyable.

To better see our engagement with services as a form of work, let’s look at them through a lens of automation. Imagine a purely hypothetical, fully automated company in some type of services business. It might be a hospital, a retail store, or an automotive repair shop; just use your imagination to really picture it. The company has no employees and so end users access its services entirely via machines. When you examine what’s happening in your mind’s eye, what you’ll see is that the company is still creating economic value. But what you’ll also see is that that value only comes about with the continued participation of the end users. When you take employees out of the equation for a thought exercise like this, the new economic role of end users shines through with glaring obviousness.

I’m not talking just about the contributions end users make with social media posts and other forms of user-generated content. I’m not even talking about the data that we contribute and how it’s used to train the machine learning that drives these systems. I’m talking about something much more fundamental. When the company is essentially just a giant machine with no employees, its operations are meaningless without end users. Its whole value proposition hinges on end users actually using the services. Without the end user experiencing the service, there is nothing.

This is how automated self-service will radically transform our understanding of the nature of work. For even as they ravage job after job in the service economy, they simultaneously open up new forms of work. We don’t yet know what this new work will be called but perhaps it will be called “experience work.”

Automated Service Platforms

Tech giants like Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google are catalysts in the automation of the service economy. The term used to describe these companies in Silicon Valley is a “platform” business. Tim O’Reilly has written an insightful book on the topic, as have Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson. A platform is something on which others can build. Small businesses might use “market platforms” like Amazon and eBay to sell things. Individuals might use “gig economy” platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and Uber to contract their labor. But the “automated service platform” is the most powerful of all platforms. That’s because it automates end users’ ability to serve themselves—and that is what contributes most powerfully to the automation of the service economy.

These engagement platforms enable tech giants to coordinate vast networks of people. As they automate, the nature of work in these companies bifurcates. Most employees will initially remain focused on carrying out ongoing service operations. Over time, more of these tasks become automated or outsourced to gig economy platforms. Medium-wage jobs will be the first to go. Low-wage jobs will be slower to disappear since they cost-effectively handle tasks that haven’t yet proven economical to automate.

Meanwhile, a small technical and entrepreneurial core focuses on shaping and managing the automated service platform. Competition for these jobs continues to intensify as do the compensation packages tech firms are willing to pay to fill these increasingly elite jobs. As one services market after another falls, automated service platforms eat into more of the services economy. Employment in the sector shrinks while the remaining workers become increasingly productive—just as happened the automation of agriculture and manufacturing. Agriculture now accounts for just two percent of US jobs, while manufacturing dropped from 25 percent of total employment in 1970 to now less than 10 percent. While it may seem hard to imagine, service jobs are now headed in the same direction.

The Rise of Artificially Intelligent Services

As a society, we are unprepared for the complexity of automated service platforms and the artificial intelligence that animates them. We have seen Facebook skew a U.S. presidential election and help drive the U.K. out of the European Union. We have seen Uber turn the taxi business on its head and Amazon upend the world of retail. And still, we remain largely unaware of the magnitude of change headed our way as machine learning fully penetrates the service economy.

Machine learning is a force that generates novelty and unexpected results. Harnessed to automated self-service, it will redefine our understanding of work. It won’t stop there, however. For as today’s service companies morph into the automated service platforms of tomorrow, they will also become artificially intelligent. Next in

We still don’t know what new forms of efficiency and service will emerge as automated service platforms shine forth with a new intelligence. How will it feel, for example, to stay in an artificially intelligent hotel or commute in an artificially intelligent rideshare? What about hospitals, schools, and magazines? The truth is that we have no idea what these services will be like once fully infused with machine intelligence.

What we can say is that artificially intelligent services will be driven by the objective functions embedded in their code. We know from experience that this “code within the code” has a deep impact on the outcomes of systems.

When that code tells the system to maximize returns for shareholders, the consequences are fairly predictable. But sometimes, as in Cambridge Analytica’s hijacking of Facebook algorithms, the consequences are unintended—and unbelievably destructive.

The job now before us is two-fold. First, we must recognize that automated service platforms will lead to mass unemployment while simultaneously redefining the future of human work. And second, we must begin redefining the code within the code of these systems so that the future of intelligence on this planet is pointed to more noble purpose.