Key Takeaways:

David Hockney is the great modern mark-maker. He brings new joy and richness to the very act of seeing, writes art critic Richard Brinsley Wylie. David Hockney’s latest book, My Window, is a visual diary of what he observed from his bed. At the age of 72, he started using iPhone and iPad screens for vivid “drawings by computer”. The role of colour in such drawings is descriptive to a degree but never confined to reality. The kaleidoscopes of light, colour, texture, form and space offer endless variety to Hockney’s probing eye. Particularly notable is the recent series of views of his estate in Normandy as the plants, trees, rivers, streams, ponds and skies undergo magical visual reshaping.

David Hockney is the great modern mark-maker. By mark I mean the merest stroke left by a brush or drawing instrument which, by itself, has little descriptive power. But skilfully placed alongside other rudimentary marks, they have the ability – in the hands of a real artist – to operate coherently, inducing the viewer to transform the ensemble of brushstrokes into a vibrant image.

A curved green smear on its own seems to describe very little, but in the context of other deft marks, it assumes the semblance of a vase or of leaves and stems of various kinds. Modern neuroscience favours context, expectation, probability and prediction for the human brain to assemble incredibly rapid perceptual shots into a “view” – rather than expecting our visual apparatus to take the equivalent of a detailed photograph.

Artists who paint freely have always known precociously how to play this game. What translates this perceptual activity into more than a routine act is that it can lead the viewer to notice overlooked aspects of what can be seen.

We can look casually at a vase and enjoy its shiny surface and the host of pretty flowers it contains. But Hockney enriches our seeing so that we become aware of other vivacious effects within the glass container.

Light rebounds and refracts sometimes with delicate glare, sometimes as tiny linear starbursts, or small wriggling gleams. The barely described petals dance with each other and with the leaves, stems, blinds and windows. Objects come to life on patterned tablecloths. Hockney is saying, visually: “Look at this.” He brings new joy and richness to the very act of seeing.

Embracing new possibilities

Hockney rose to fame during the swinging 60s and the advent of Pop Art. Elegantly executed, his spare paintings and graphic works drew on a wider range of artistic imagery than most Pop Art, as in Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970-71).

His move from drab England to sunny California – and its greater tolerance of gay culture – resulted in virtuoso paintings with brilliant colours and geometrical outlines, such as Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool (1966).

So successful was this period that he could have continued producing similarly marketable works. But, as always, Hockney moved restlessly on. He has produced paintings of spatial motifs that overtly negate traditional perspective, multi-viewpoint photographs and videos, and portraits of every kind.

At the age of 72, he started using iPhone and iPad screens for vivid “drawings by computer”. His latest book My Window – a visual diary of what he observed from his bed each morning between 2009 and 2012 – contains a dazzling compilation of these drawings.

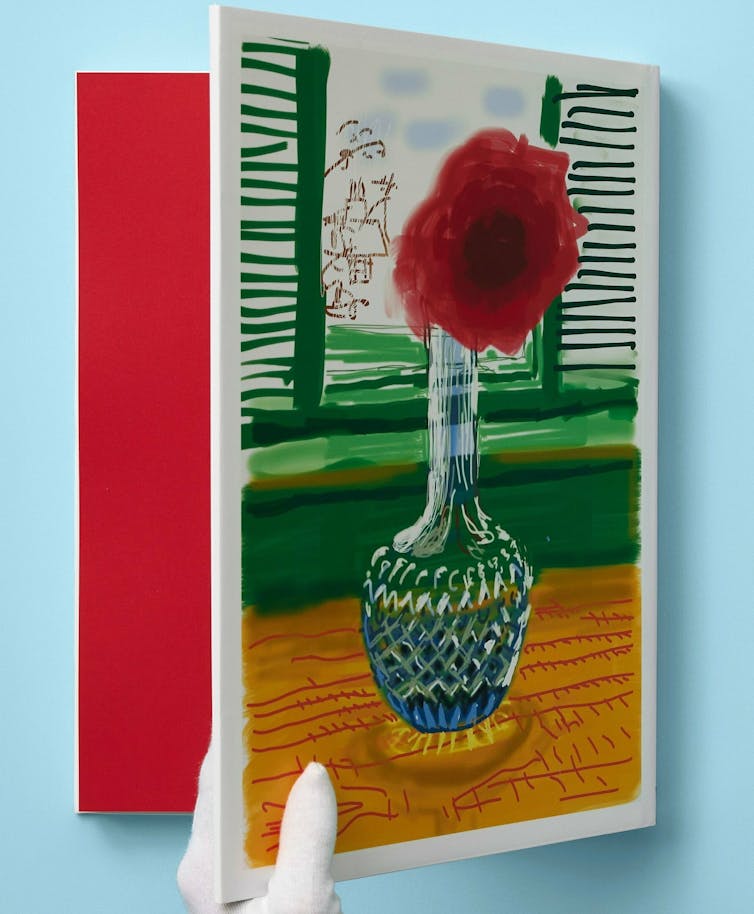

In No. 281, 23 July 2010, iPad Drawing, we see a perfect example of Hockney’s way of seeing and presenting: the red explosion of the flower from a dark centre is magnificent, in effect “painting with light” on the iPad screen.

But the flower in the drawing is only part of Hockney’s brilliance. The vase is extraordinary. The light stripes on the vase’s neck are registered in the upper part of its cut-glass body as calligraphic wiggles. The lower half of the vase is taken over by a kind of visual basket-work. At its base, the tapering grooves emit a glowing azure.

Paradoxically, the halo of light cast immediately on the tablecloth below the base radiates a sunburst of brilliant yellow. Even more unexpectedly, a corona around this “sun” is a blurry dark orange. The rapid rough lines of the sketchy blinds on either side play assertive visual jazz, beside which the skittish outlines of a distant house and trees – barely outlined – test the viewer’s determination.

The role of colour in such drawings is descriptive to a degree but is never confined to reality. As his intensely colourful landscapes of Yorkshire attest in vivid blues, reds and purples, Hockney uses startling colours to feel and express the forms and space that orchestrate our acts of seeing.

Light, colour, texture

Produced in gleaming colour, My Window opens with almost 100 iPhone drawings from 2009. The small screen and relatively crude marks rely even more on visual context than the larger succession of iPad drawings, with their wider screen and more varied marks. These reveal Hockney’s progressive command of the greater subtlety of the iPad.

The constant iteration of the view from his window with vases of refreshed flowers might sound repetitious. But the kaleidoscopes of light, colour, texture, form and space with the passing of time and seasons offer endless variety to Hockney’s probing eye.

From about April to August … the sun would wake me up. I would never have thought to do a sunrise without the iPhone. My friend John would put different flowers there every two or three days. I drew on the iPhone with my thumb but when the iPad came out in 2010, I immediately got one … I could draw with a stylus, and get more details in.

The rapidity of this medium – no slow-drying paints – facilitated extensive sets of images that swiftly record transformations over time. Particularly notable is the recent series of views of his estate in Normandy as the plants, trees, rivers, streams, ponds and skies undergo magical visual reshaping – casual looking misses so much.

One of the challenges of future Hockney research will be to look at his redefinition of space and time in painting, which normally portrays a specific if extended moment, not a continuous sequence of times as in his later landscapes and flower pieces. In Hockney’s hands, the traditional pursuit of mark-making on a flat surface is being put to more experimental ends than seemed possible.