Key Takeaway:

Water is essential for development, production, and consumption, but we are overusing and polluting it. Eight safe and just boundaries have been identified for five domains: climate, biosphere, water, nutrients, and aerosols. Humans have already crossed these boundaries for water, but the minimum needs of the world’s poorest to access water and sanitation services have not been met. Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to solve water problems and help achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but its water footprint is significant. AI uses water for cooling servers and producing energy, and its hardware production involves resource-intensive mining for rare materials. As AI becomes more integrated into society, its water footprint will inevitably grow. The technology sector’s water demand is so high that communities are protesting against it, as it threatens their livelihoods. As water becomes increasingly expensive and scarce, companies are strategically placing their data centers in developing countries, creating a dilemma between economic benefits and strain on local water resources availability.

Water is needed for development, production and consumption, yet we are overusing and polluting an unsubstitutable resource and system.

Eight safe and just boundaries for five domains (climate, biosphere, water, nutrients and aerosols) have been identified beyond which there is significant harm to humans and nature and the risk of crossing tipping points increases. Humans have already crossed the safe and just Earth System Boundaries for water.

To date, seven of the eight boundaries have been crossed, and although the aerosol boundary has not been crossed at the global level, it has been crossed at city level in many parts of the world.

For water, the safe and just boundaries specify that surface water flows should not fluctuate more than 20 per cent relative to the natural flow on a monthly basis; while groundwater withdrawal should not be more than the recharge rate. Both of these boundaries have been crossed.

These thresholds have been crossed even though the minimum needs of the world’s poorest to access water and sanitation services have not been met. Addressing these needs will put an even greater pressure on already-strained water systems.

AI’s potential

Technological optimists argue that artificial intelligence (AI) holds the potential to solve the world’s water problems. Supporters of AI argue that it can help achieve both the environmental and social Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), for example by designing systems to address shortages of teachers and doctors, increase crop yields and manage our energy needs.

In the past decade, research into this area has grown exponentially, with potential applications including increasing water efficiency and monitoring in agriculture, water security and enhancing wastewater treatment.

AI-powered biosensors can more accurately detect toxic chemicals in drinking water than current quality monitoring practices.

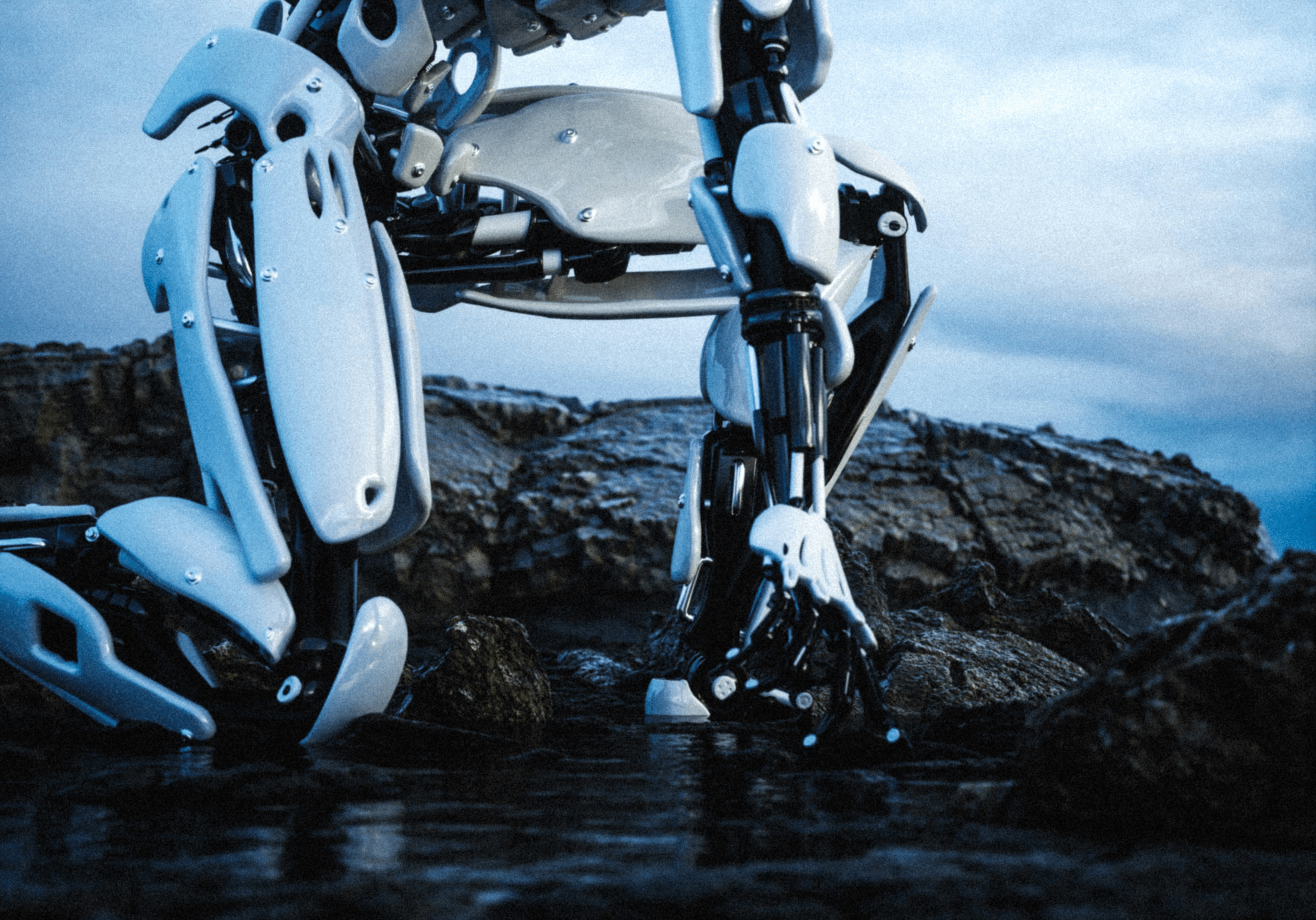

The potential for AI to change the water used in agriculture is evident through the building of smart machines, robots and sensors that optimize farming systems.

For example, smart irrigation automates irrigation through the collection and analysis of data to optimize water usage by improving efficiency and detecting leakage.

As international development scholars who study the relationship between water, the environment and global inequality, we are curious about whether AI can actually make a difference or whether it exacerbates existing challenges. Although there is peer-reviewed literature on the use of AI for managing water and the SDGs, there are no peer-reviewed papers on the direct and indirect implications of AI on water use.

AI and water use

Initial research shows that AI has a significant water footprint. It uses water both for cooling the servers that power its computations and for producing the energy it consumes. As AI becomes more integrated into our societies, its water footprint will inevitably grow.

The growth of ChatGPT and similar AI models has been hailed as “the new Google.” But while a single Google search requires half a millilitre of water in energy, ChatGPT consumes 500 millilitres of water for every five to 50 prompts.

AI uses and pollutes water through related hardware production. Producing the AI hardware involves resource-intensive mining for rare materials such as silicon, germanium, gallium, boron and phosphorous. Extracting these minerals has a significant impact on the environment and contributes to water pollution.

Semiconductors and microchips require large volumes of water in the manufacturing stage. Other hardware, such as for various sensors, also have an associated water footprint.

Data centres provide the physical infrastructure for training and running AI, and their energy consumption could double by 2026. Technology firms using water to run and cool these data centres potentially require water withdrawals of 4.2 to 6.6 billion cubic metres by 2027.

By comparison, Google’s data centres used over 21 billion litres of potable water in 2022, an increase of 20 per cent on its 2021 usage.

Training an AI at the computing level of a human brain for one year can cost 126,000 litres of water. Each year the computing power needed to train AI increases tenfold, requiring more resources.

Water use of big tech companies’ data centres is grossly underestimated — for example, the water consumption at Microsoft’s Dutch data centre was four times their initial plans. Demand for water for cooling will only increase because of rising average temperatures due to climate change.

Conflicting needs

The technology sector’s water demand is so high that communities are protesting against it as it threatens their livelihoods. Google’s data centre in drought-prone The Dalles, Ore. is sparking concern as it uses a quarter of the city’s water. The Associated Press looks at Google’s water consumption in The Dalles, Ore.

Taiwan, responsible for 90 per cent of the world’s advanced semiconductor chip production, has resorted to cloud seeding, water desalination, interbasin water transfers and halting irrigation for 180,000 hectares to address its water needs.

Locating data centres

As water becomes increasingly expensive and scarce in relation to demand, companies are now strategically placing their data centres in the developing world— even in dry sub-Saharan Africa, data centre investments are increasing.

Google’s planned data centre in Uruguay, which recently suffered its worst drought in 74 years, would require 7.6 million litres per day, sparking widespread protest.

What emerges is a familiar picture of geographic inequality, as developing countries find themselves caught in a dilemma between the economic benefits offered by international investment and the strain this places on local water resources availability.

We believe there is sufficient evidence for concern that the rapid uptake of AI risks exacerbating the water crises rather than help addressing them. As yet, there are no systematic studies on the AI industry and its water consumption. Technology companies have been tightlipped about the water footprint of their new products.

The broader question is: Will the social and environmental contributions of AI be overshadowed by its huge water footprint?