The interconnection of creativity with human intelligence, individuality, and neurological processes, is a dynamic and exciting field to study and to work in. Over time, creativity has been of central interest to disciplines such as cognitive science, philosophy, education, technology, economics, linguistics, psychology, and neuroscience — just to mention a few.

But, what does creativity mean? Is it a concept with one sole definition or can it contain several connotations?

Creativity is generally accepted to be an occurrence that involves unexplored and imaginative ideas turning into reality, or the formation of a new physical object of great value. In both cases, it is something that requires time and action, a manipulation of what is our mental and spiritual pool of resources recombined in unexpected and unique ways.

Creativity works mysteriously; it appears difficult to define all its intrinsic features and mechanisms because its genesis is not completely clear. Creativity can be part of our personality or something that presents itself in a given situation or context that is out of the ordinary. It does not have a single manifestation, and it can be found inside of everybody in some form.

What is Computational Creativity?

According to Colton and Wiggins, Computational Creativity is “The philosophy, science and engineering of computational systems which, by taking on particular responsibilities, exhibit behaviors that unbiased observers would deem to be creative.”

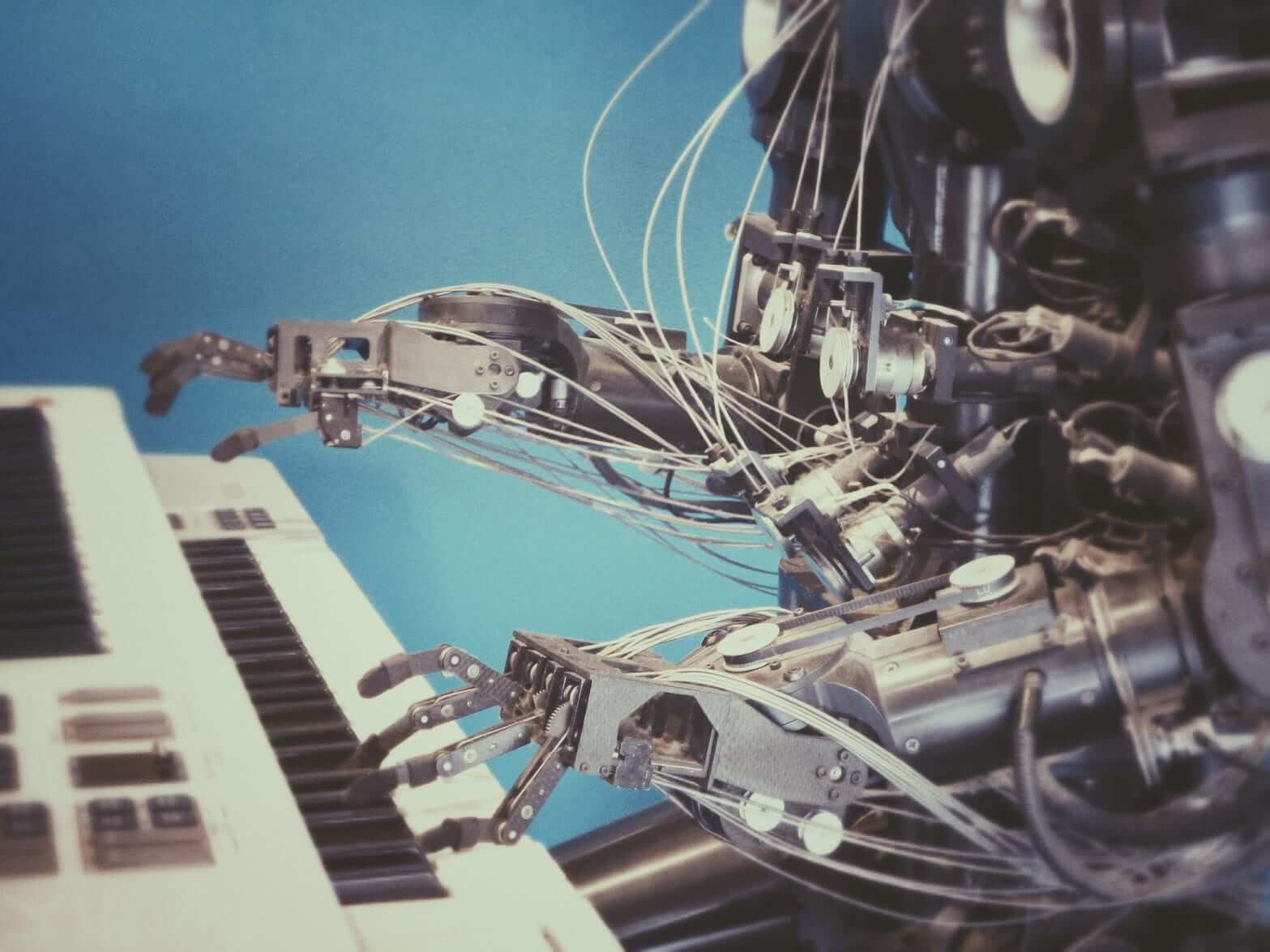

In recent years, we have seen AI applied with success to different kinds of art, from music, to filmmaking, to design and visual arts. This is a hot topic: museums, galleries, AI experts and computing artists are debating if AI can or should be creative, how far its boundaries in the creative process could be pushed, if its role would be merely of assistance to the artist, or if one day AI will become a more structured partner or an artist in its own right.

AI can learn to mimic the data it has been trained on reaching great results, but it has limitations related to the concept of creativity being a subjective matter, “It’s easy for AI to come up with something novel just randomly. But it’s very hard to come up with something that is novel and unexpected and useful.” — John Smith, Manager of Multimedia and Vision at IBM Research.

Considering that humans themselves have difficulties to define this concept, it appears clear that even the most sophisticated algorithm can not do it because a lot of the creative process is still unknown. As Jason Toy, CEO of Somatic, points out, “ Can we take what humans think is beautiful and creative and try to put that into an algorithm? I don’t think it’s going to be possible for quite a while.”

In all this matter there are no unidirectional visions, and the questions that AI has raised are becoming more and more urgent to address for many stakeholders that operate in the art sector and who are preparing for the challenges and opportunities that this technology can bring.

Examples in visual arts

At the moment AI is very trendy, involving a number of professionals working on several aspects of the implications of this technology on the arts. We are talking of authenticity, authorship, legality, validity and so on.

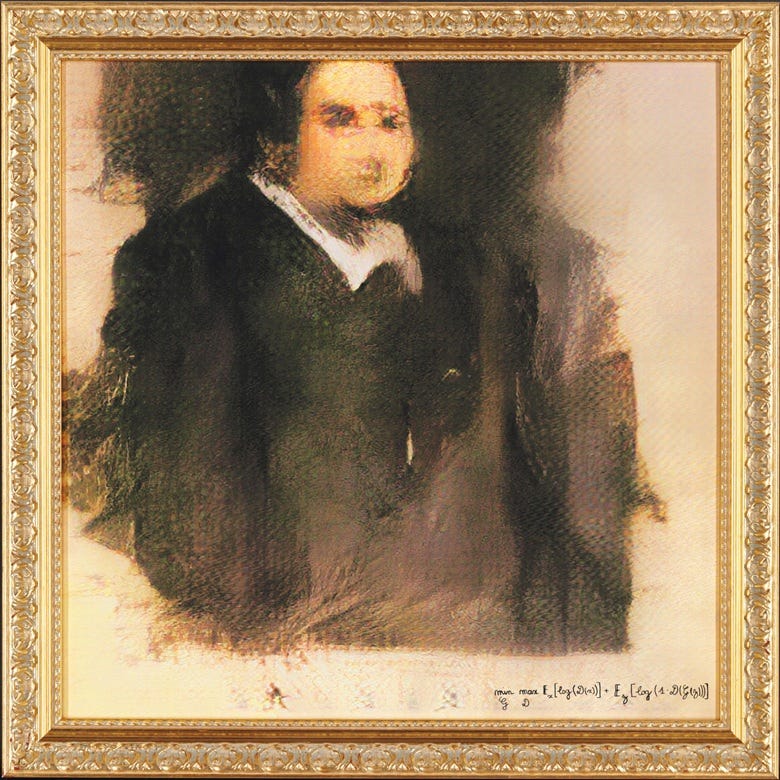

The end of 2018 has seen Christie’s becoming the first auction house to offer a work of art created by an algorithm at the unexpected price of $432,500. The piece, Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, is part of a collection of an imaginary family and its name is a tribute to Ian Goodfellow, the researcher in machine learning that invented the algorithm called Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which are the base of the work done by Obvious, the French collective behind the portrait.

GANs use two neural networks that contest each other in order to generate something that looks authentic to the human eye: the so-called generator creates new images by trying to fool the discriminator into thinking the generated images are real. The machine has been previously fed thousands of input images with the goal of creating a new one that shares the same features.

The point of Obvious was to prove that a machine can emulate creativity, but the auction has raised controversial positions in the field. Some criticism has surfaced due to the fact that the price of the auction grew mainly as a result of a media circus ahead of the auction itself; other, from the fact that the machine has been taught what to produce, being under the curatorship of the Paris-based collective, and that the AI-generated art lacks creativity

In this exciting environment, the AI world brings to the scene another algorithm that is focusing on the creative aspect, more that on the generativeone. The Art and Artificial Intelligence Lab at Rutgers University, with Professor Ahmed Elgammal, is working with a system called AICAN.

The base is similar to GANs, giving two neural networks in opposition to each other, but AICAN — A Creative Adversarial Network — is programmed to reach some sort of novelty through stylistic ambiguity, and it seems to do very well with abstract painting. The design of the algorithm is based on the theory of the process creativity by Colin Martindale and it is not trained on specific aesthetic or style. The result is a new image that contains a “balanced” novelty, not too exaggerated to push viewers away, and not mere emulation of an established style. The framework is set by humans, but the machine is able to choose the features of the art that it generates such as style, composition, colors, title and so on. AICAN’s work has been exhibited at venues in Frankfurt, Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco.

Tom White is an artist and lecturer at the University of Wellington School of Design in New Zealand, who has attracted a lot of attention in the machine learning community. He uses neural networks and creative coding to make his prints and represents the world not like a human being can see it, but how an algorithm does. The prints are optical illusions, but only computers can see the hidden image. White says he designs his prints to “see the world through the eyes of a machine” and make “a voice for the machine to speak in”. His work has been seen as an expression of AI becoming smarter and beginning to think creatively.

Karthik Kalyanaraman, co-curator of the Nature Morte exhibition “Gradient Descent” — a group exhibition featuring works created entirely by artificial intelligence — says, “If a machine can make humanly surprising, stylistically new kinds of art, I think it is foolish to say well it’s not really creative because it doesn’t have consciousness”. The exhibition explores the intersection between artificial intelligence and contemporary art, providing the viewer with a vision of what art could be in the post-human age.

Mike Tyka has a background in Biophysics and currently works at Google on Machine Learning in Seattle. He became prominent as an AI artist in 2015 working with artificial neural networks as an artistic medium and tool. His latest generative portraits series, titled “Portraits of Imaginary People” has been shown in Linz, at the New Museum in Karuizawa (Japan) and at the Seoul Museum of Art. It explores the hidden space of human faces by using GANs to create and to draw portraits of imaginary people.

“Drawing or painting was never my strength, as I never managed to get the same control over my hand muscles as when I write code. So instead of fighting against my body to produce an image I might have in my head, I preferred to learn how to instruct machines to do that.” — Mario Klingemann.

Mario Klingemann is an artist in residence at Google Arts and Culture and calls himself a neurographer. His work includes collaborations with prestigious institutions like the British Library, Cardiff University and the New York Public Library. His most recent effort, an installation titled Memories of Passersby I , has been sold for 40,000 GBP through auction by Sotheby’s and is a composition of multiple GANs, two screens, chestnut wood console, which hosts AI brain and additional hardware.

The machine works in real time spitting out unreal and somewhat disturbing portraits of imagined male and female faces (called by Klingemann “The Francis Bacon effect”). The faces are displayed on the screens and provide a unique experience for the audience.

Mario Klingemann’ s collections use algorithms that are not trained under any curatorship and they can not be considered human-curated final products, but like he says, “The machine creates faces that change and get lost all the time. It observes itself and tries to create a new one continuously in a retrospective cycle.”

Enhancing creativity through AI

Regarding the production of art, in the relationship that occurs between human brain and machine, there is much attention on the possibility of the machine being creative.

This aspect has its own reason, involving several other disciplines, posing multiple doubts (i.e., philosophical, legal, psychological, ethical, societal, etc.) and raising criticisms.

The pure simple, but yet big question is: can AI create true art?

As we saw, nobody has a final answer as nobody can provide a final statement on what creativity is. Of course we can talk of some of the features of creativity and generally recognize them as an integral part of it, but due to its subjective nature the discussion is still open.

When we read about the work of Prof. Elgammal at Rutgers, he says that in his experience AI gives better results towards conceptual art and that the relationship between the human and the machine is shaped to be part of an artistic process that see two components involved, one human and one artificial, giving a great space to the machine for becoming a medium. But when Mario Klingemann is asked if he sees himself collaborating with the machine, we get a different and perhaps unexpected answer, “ So for me AI is just one tool in a long history of tools that was bound to be used for artistic purposes. But I would say I use AI as a tool and the works that I make with this tool are mine and not a collaboration, in the same way I would not call a hammer or a piano a collaborator” .

Therefore, is AI a medium or is it just a tool in the hands of the human artist?And why many artists and historians feel threatened and resist the concept of art created by a machine? Has this something to do only with the modern concept of artist as a sole creator? Is it because we cannot have a clear idea of what creativity is and how we reach a process that can be identified as creative? Maybe we should try to understand what AI art could really mean.

In the future perhaps we will develop technology that can create without supervision or direction. But, should this be the goal of AI even if technically possible? When asked, Rob High — Vice President and Chief Technology Officer for IBM Watson — says, “It is not our goal to recreate the human mind — that’s not what we’re trying to do. What we’re more interested in are the techniques of interacting with humans that inspire creativity in humans”.

So, what if AI would become a presence in the life of the artist able to inspire new ideas in a collaborative way on a more regular basis, enhancing the creativity process? What if AI is something that still needs to find its real place in the human creative process and that does not antagonize, but can work jointly with the inner pool of resources of the artist to produce a new idea through inspiration?

For example, GANs can produce images that surprise even the artist presiding over the process because they can provide a series of deformed faces. Psychologist Daniel Berlyne has found that novelty, complexity, ambiguity, surprise and eccentricity show to be strong and powerful inspiration in art works, and GANs can definitely provide all this. “It’s about the augmentation of creativity. In the end, the human really is the one being creative, and it’s more about how can you get better efficiencies”, says John Smith.

Libre AI: an alternative for the artist

All the experiences presented so far, from the Obvious’ portrait to the installation of Mario Klingemann that spits out unsettled faces in real time, require the artist to be well acquainted with the field of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. This poses a great limitation for artists who would like to engage in these techniques, but they have a lack of skills in AI and ML.

Libre AI’s mission is to disseminate the benefits of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning and make them accessible to the world. The focus on democratizing this technology, bringing it to a wider audience, pushes Libre AI not only to experiment with art generated by machines, but also to look forward to working with artists keen to experiment AI techniques in their art production.

In particular, Libre AI aims to put the artist (with no skills in AI) in the position of co-creating the experience, registering the emotional and psychological impact that the new technology brings to the creative process itself. In all this the artist has a say and leading role, actively collaborating with the technology.

Another aspect that Libre AI would like to investigate is the effect that art generated in collaboration with AI evokes in people. A painting can be just a nice addition to the decor in a room, but as Robert Motherwell said, “art is an experience, not an object”. Art can have the potential to be a powerful life-changing tool, creating a transformational experience for the viewer and for the artist.

Standing in front of an artwork, the soul of the viewer interacts with the art and the artist, co-creating and re-creating the whole thing. It would be interesting to understand how AI can affect the perception and participation of the audience in a nontraditional setting.

Computational creativity can be a lot of things, but one way to set this matter is to decide for ourselves what computational creativity could mean. We want to push the idea that AI can enhance the creativity in artists (and not only), prospecting a collaboration between the human mind and the machine in an artist-centric way.

About the Author

This article was written by Beth Jochim, Creative AI Lead at Libre AI. See more.