Coffee has become a staple in our every day routine. Most people know exactly which coffee shop, the kind of roast, or the type of coffee they relish most. But, as you pay for your coffee at your favorite store, have you ever wondered who is taking the biggest share of the proceeds? Who are the biggest winners and losers in the coffee industry?

The way humans came across coffee is still unknown but one of the widely accepted theories is that coffee was first discovered in Ethiopia before the 9th century, when a shepherd noticed that his goats were unable to sleep after eating red berries, which were coincidentally coffee beans, from a certain shrub. In the 15th and 16th century, coffee started being grown in the Arabic Peninsula and the Middle East, with the earliest records of coffee drinking dating back to the 15th century in Yemen. It wasn’t until the late 17th century that the drink made its way into Europe through Dutch, Parisian and Venetian traders, where it gained popularity and started being planted all around the world.

Since then, coffee has become a staple of our every day routine. According to the National Coffee Association, over 2.25 billion cups of coffee were consumed every day around the world. For many, a good day does not start without a fresh ‘cup of joe’. The Pavlovian response that coffee incites is so strong that the smell alone can sharpen one’s mind. Coffee is also one of the most common social activities with the phrase ‘Let’s meet for a coffee’ becoming nearly synonymous to ‘Let’s catch up’. Most of our favorite sitcoms were built around the social dimension of coffee with recognizable coffee shops such as ‘Central Perk’ in Friends, ‘Monk’s Cafe’ in Seinfeld and ‘Cafe Nervosa’ in Frasier.

From Shrub to Cup

Coffee flourishes in the sub-tropical and equatorial regions. The history of harvesting coffee is closely tied to colonialism, since coffee, just like cotton, sugar and other commodities, played a crucial role in global trade. As a result, today’s largest coffee producers are countries that were previously colonized by European empires. For example, the Portuguese introduced coffee to Brazil, the French to Vietnam, the Spanish to Columbia, and the Dutch to Indonesia. Since then, the population of the coffee producing nations became dependent on the income of the crop and have been supplying raw coffee to meet global demand for generations.

Generally, as consumers, we rarely think about the evolution and process that goes into what we purchase. For coffee specifically, we know how strong we like our roast, whether we prefer espressos over americanos and — if we are really curious — what kind of bean we are consuming. Below, we will go over the journey of coffee, from the shrub to the cup, which can be summarized in four key steps:

- On the farm: Farmers grow and pick coffee beans then process them to extract the raw green beans

- On the ship: Coffee is packed, sold and traded around the world

- In the roaster: Green coffee is roasted to various levels to extract flavors

- In the cup: Coffee beans are grounded and the flavors extracted into a lovely morning cup of sunshine

1. On the farm

Every coffee bean is ‘born’ on a farm. The coffee plant is a small tree or shrub with smooth leaves. It takes around 5 years to mature and produce its first harvest, and has a productive lifespan of around 25 years. There is usually one major harvest a year, which can however vary depending on the type of coffee bean and climate. At every harvest, the plant’s fruits, the coffee berries, are picked, dried, and then milled, to separate the outer red shell from sought-after green coffee bean.

Planting and harvesting coffee are tasks led mainly by small scale growers. Around 80% of the world coffee beans are produced by 25 million small scale farmers operating on farms of often around 1–5 hectares. These farmers have limited bargaining power or control over prices, and their profits are often squeezed by large coffee traders. To help protect the farmers, some organizations have been formed such as the Fairtrade Foundation, an entity that tries to ensure that farmers obtain a fairer price for their raw coffee. If interested in promoting the farmers’ welfare, try to purchase brands that are Fairtrade Certified.

2. On the ship

Green beans are transported out of the coffee producing nations and traded around the world. The stripped down green coffee beans are sold to intermediariesand shipped through a global coffee supply network. The intermediaries can include government agents who purchase raw coffee from local farmers, bundle it, then sell it on auction, large exporters who purchase and transport the coffee beans around the world, and suppliers who purchase the coffee beans from the exporter and sell it to roasters. In 2018, around 7.2 billion kg of raw green coffee have been exported worth around over $19 billion.

3. In the roaster

Green coffee should be roasted before consumption. In the roastery, coffee goes through the roasting process, during which the chemical and physical properties of the green bean are changed to bring out the lovely complex coffee flavors that make our nostrils flair every morning. In the roaster, the coffee bean loses around 12 to 20% of its weight, which consists mainly of moisture and gases produced by chemical reactions. After roasting, coffee beans become darker in color are ready for consumption; they are packaged then sent to retailers and coffee shops.

Roasting often occurs on large scale and rarely in the coffee producing regions. The top 10 roasting and exporting nations do not include a single coffee producing nation. Advanced economies with higher GDP per capita are in control of this part of the value chain. They purchase the green beans at very low rates from the coffee producers, roast them and export them at a premium. Switzerland exports, on average, the priciest roasted coffee in the world, followed by Italy, Germany and France. Compared to the minimum green coffee prices published by Fairtrade of around 1.4$ per pound, the value in roasting coffee bean is much higher with prices ranging from $3 to over $14 per pound for coffee roasted in Switzerland — 10x the Fairtrade green coffee farmer prices.

Nowadays, roasting on smaller scale is becoming more popular. Many specialty shops started roasting green coffee inhouse to reduce their costs, while having more control over the roasting process to ensure consistency, quality and freshness. When serving premium coffee, using freshly roasted beans is key since coffee beans “degas” around 1 to 2 weeks after roasting, losing some of their unique flavor and aromas.

4. In the cup

Grinding and brewing the beans are the last steps before taking that first morning sip. Grinding breaks down coffee into finer particles. The fineness varies depending on the coffee roast type and brewing method. However, whether the coffee is an espresso, siphon or brewed, the objective remains the same: hot water extracting flavors, caffeine and other relevant compounds from the coffee grounds for the consumer to savor.

Who are the biggest winners and losers in the coffee business?

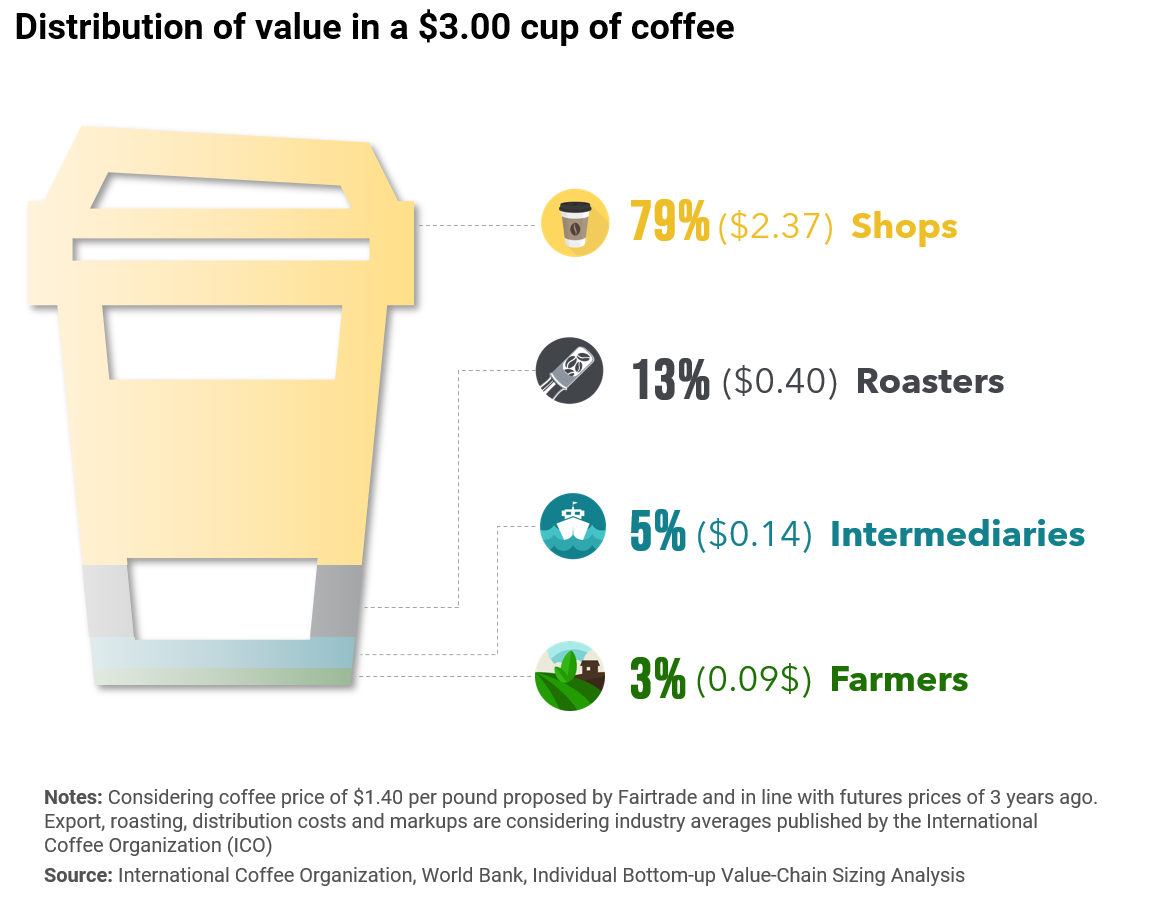

The best way to wrap our heads around this question is to look at the economics of a coffee cup and how it is distributed across the key players of the value chain.

The biggest loser: Coffee farmers are fighting an uphill battle. As small scale growers in developing countries, they are often not supported sufficiently by their local government and are at the mercy of the larger profit-driven companies across the value chain.

Farmers are barely able to survive. On average, the yield for a 5 hectares farm is around 10,000 pounds of coffee. For coffee farmers in Latin America selling their coffee at Fairtrade prices of around $1.40 per pound — which are above current market prices — and operating at a breakeven price of $1.20 per pound, they will only make a profit of $2,000 per year, which is equivalent to $160 per month. When not protected by Fairtrade, farmers often operate below breakeven price. According to Reuters, desperate coffee growers in Latin America are switching to other crop such as coca, the plant used in the production of cocaine, in order to survive.

The biggest winners: Roasters and retailers control over 90% of the value in the $200+ billion coffee industry. Big producers such as Nestle — known for Nescafe and Nespresso — and JDE — with many brands around the world including Carte Noire and L’Or — are benefiting from operating at large scale and with extremely healthy profit margins due to the very low raw material cost and the much higher price point commanded by roasted coffee. Coffee is often roasted in Europe, in countries like Switzerland, Italy and France, and North America. According to the ‘Coffee Barometer report, the highly profitable nature of this sector has recently resulted in a series of consolidations, during which largest roasters acquire smaller players to control market share.

Retailers are also some biggest winners in the coffee business. Starbucks is the prime example, with its meteoric rise from humble beginnings in 1971 to a $90 billion coffee empire with a commanding presence across the entire coffee value chain. Starbucks buys coffee from all around the world, but also owns its own farms in Latin America and roasteries around the world. The economics of controlling the value chain has allowed Starbucks to maximize margins while controlling product quality and building a brand that currently dominates the coffee retail sector, with a widespread presence of nearly 30,000 stores globally.

Wrap-up — The last sip

I would like to highlight two key takeaways from this overview. Firstly, farmers have drawn the short end of the stick; they are not compensated enough for their hard work. The great coffee we drink every day is mainly thanks to their year-long commitment to the land. Secondly, coffee economics are indicating that owning a coffee shop can be an extremely profitable venture.

- The coffee sector is not doing enough to protect farmers and ensure value chain sustainability. In the past, the coffee producing nation were required to produce crop for the colonizer. Nowadays, fueled by global demand, these countries seem to have a similar fate, however the hands of ‘Big Coffee’ companies. Many of these companies claim to have sustainable programs to promote sustainable coffee production and improve equity by distributing more value to farmers. However, that effort seem to be a drop in the ocean when compared to the profits and revenue generated. According to Hivos — a development aid organization — almost none of the profits of the big corporations are reinvested in sustainability.

- Owning a coffee shop can be extremely profitable. While benchmarking, modeling the economics of the coffee value chain and estimating a coffee shop’s average profitability, I concluded through sensitivity analyses — which I am considering to publish in a subsequently article — that owning a coffee focusing on premium coffee and inhouse roasting can be a great idea in a location with sufficient demand. Nevertheless, profitability can vary greatly depending on the country where operated and local trends.

So, the next time you are sipping on a hot cup of morning brew — hopefully with beans that are Fairtrade certified to protect the hardworking and underpaid farmers — remember, you are paying more for the branding, marketing and fancy design of the highly profitable coffee shop than for the actual coffee beans that you are consuming.

About the Author

This submitted article was written by Jimmy Gammayel, a Senior Engagement Manager at Oliver Wyman with over 10 years of consulting and industry experience in Fiscal management, Public policy and Energy. Jimmy worked with various governments and companies on topics such as strategy definition, portfolio management, operational improvement and transformation programs. Contact Jimmy.