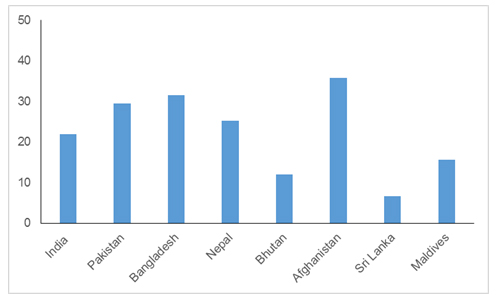

The countries comprising the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) region (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives) commonly known as South Asia face serious healthcare affordability and accessibility challenges. According to World Bank national estimates, South Asian countries houses more than 390 million poor people and a very significant percentage of total population lies below national poverty line (Figure 1). This large number of population is quite unlikely to afford private healthcare services and heavily dependent on the public healthcare facilities.

Figure 1: % of population below nationally determined poverty line

Source: World Bank

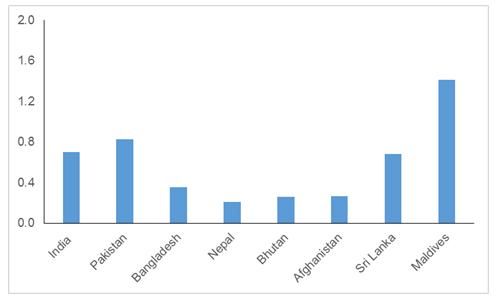

Apart from just high poverty levels, the availability of doctors is another critical challenge. As per World Bank data except Maldives, every SAARC country has less than 1:1000 doctor to population ratio which is an area of concern (Figure 2). The availability of qualified doctors in the rural areas is dismal and people often tend to self-medicate or take treatment from self-proclaimed doctors who often have no formal education in practicing medicine. It is also important to note that more than 50% South Asian population amounts to approximately 1.17 billion lives in rural areas that often has to travel to cities to access secondary and tertiary care raising tough accessibility barriers.

The high cost of travel to urban health centers coupled with a lack of awareness make the situation worse. Hence, it can be argued that the basic health care demography for these South Asian countries is reasonably identical, and the problem of health care can also therefore be looked at from a regional level rather than in the context of an individual country.

Figure 2: Number of doctors (physicians) per 1000 people

Source: World Health Organization

These severe affordability and accessibility barriers to universal quality healthcare demands for innovation in the way care in being delivered both to the poor and people living in rural areas. To understand innovation in South Asia, things need to be put into right perspective. Innovation in health care is not only about technological innovation or new systems of health care financing or upcoming health care delivery models targeting a vulnerable population. Health care innovation is a mix of all the abovementioned elements, which covers all aspects from diagnosis to delivery of service to the end customer, which is the patient in this case.

Often, the misconception is that technological innovation is confined to the sophisticated labs of developed nations. The increasing adoption of frugal innovation by many technological firms has changed this notion dramatically in the past few years especially in the area of health care diagnosis. Intel in India launched a device in 2015 called Lifephoneplus, which enable people to take an ECG and monitor glucose levels by themselves. This device uses the existing bluetooth and wireless network to transfer the health information record by phone, from which it can then be sent to the doctor directly.

Since 2007, GE Healthcare, one of the biggest providers of health care systems, has been developing portable and battery-operated ECG systems out of India’s labs, and these are already being used in rural areas in the developing world. The company has recently claimed to launch the first CT scanner made out of its India facility in 2015 for the developing market, keeping in mind the twin big challenges of affordability and accessibility. The challenges of the developing world are very unique and therefore the technological innovation needs to be tinkered in a way that it takes care of local needs and challenges.

South Asian countries have witnessed nearly a wind of various telemedicine initiatives and, of late, mobile apps operating at different levels and scale. Some examples include Apollo Telemedicine and iClinics in India, mPower in Bangladesh, and Aman Telehealth in Pakistan, among many others. The telemedicine-based business models leverage the information and communication technologies to act as a bridge connecting rural patients with qualified doctors in the urban areas and could be effective in improving the outcomes especially in primary care. What is more interesting is the acceptance that telemedicine seems to have generated among the governments of the South Asian countries. India has recently announced that an e-Health authority will be set up in 2015, while the Maldives and Nepal and have national telemedicine helplines in place since 2011. But Telemedicine alone has limited capacity to address the vast healthcare needs in South Asia. There is certainly a need for fostering effective partnerships to increase the geographical reach, impact and service offerings.

So what are the prospects for health care innovation in South Asia? One possibility is that the next wave of innovation in health care will be defined by increasing partnerships, such as those being implemented on a PPP model, where PPP stands for public, private, and people. For instance, the coupling of telemedicine and other innovative health care delivery models with public insurance schemes could be very effective in addressing the huge unmet need of quality rural health care in developing nations. The pairing of the low-cost surgery center, Narayana Health, with state government–supported micro insurance schemes in which poor people pay a premium of only $4–$6 annually in India is one such great success story.

The immediate need is not only for stand-alone frugal innovations or new delivery mechanisms, but devising a way to better integrate the various actors across the health care delivery value chain. The governments in South Asian countries need to upgrade their role from being merely a support provider to that of being a key enabler to bring all stakeholders on a single platform. If low-cost medical devices and technology-based frugal innovation are not being implemented in public health care systems then the potential impact of these advancements will be very limited.

The health care delivery services could also be contracted to the innovative and effective private health care providers by the different governments so that the much-needed quality primary care services are provided in the rural areas. The public insurance schemes supported by the government can be used as payment for these services. The health care innovation driven by the private sector brings in expertise and ideas but the scalability can only be achieved from active government participation in it, and not merely support. Therefore, this may be the right time for both the government and the private sector to reconsider the current innovation ecosystem in the health care sector in South Asia from the lens of active collaboration and setting the clear standards for service delivery.

Given that both of the challenges and solutions to healthcare look similar for South Asian countries, it may also be a good idea to form a regional cooperation model to foster innovation in healthcare. Different countries can both share and learn from each other experiences in adopting innovative healthcare delivery practices. The lessons learned from the establishment of SAARC as a regional multilateral institution could also be leveraged in this regard.

______________________________________________________

About the Author

This article was written by Anshul Pachouri of Asia Pathways. Asia Pathways is the blog of the Asian Development Bank Institute which was established in 1997 in Tokyo, Japan, to help build capacity, skills, and knowledge related to poverty reduction and other areas that support long-term growth and competitiveness in developing economies in the Asia-Pacific region. Anshul is currently working on strategy practice at a global consulting firm based in India.