Imagine you sit down and pick up your favourite book. You look at the image on the front cover, run your fingers across the smooth book sleeve, and smell that familiar book smell as you flick through the pages. To you, the book is made up of a range of sensory appearances.

But you also expect the book has its own independent existence behind those appearances. So when you put the book down on the coffee table and walk into the kitchen, or leave your house to go to work, you expect the book still looks, feels, and smells just as it did when you were holding it.

Expecting objects to have their own independent existence – independent of us, and any other objects – is actually a deep-seated assumption we make about the world. This assumption has its origin in the scientific revolution of the 17th century, and is part of what we call the mechanistic worldview. According to this view, the world is like a giant clockwork machine whose parts are governed by set laws of motion.

This view of the world is responsible for much of our scientific advancement since the 17th century. But as Italian physicist Carlo Rovelliargues in his new book Helgoland, quantum theory – the physical theory that describes the universe at the smallest scales – almost certainly shows this worldview to be false. Instead, Rovelli argues we should adopt a “relational” worldview.

What does it mean to be relational?

During the scientific revolution, the English physics pioneer Isaac Newton and his German counterpart Gottfried Leibniz disagreed on the nature of space and time.

Newton claimed space and time acted like a “container” for the contents of the universe. That is, if we could remove the contents of the universe – all the planets, stars, and galaxies – we would be left with empty space and time. This is the “absolute” view of space and time.

Leibniz, on the other hand, claimed that space and time were nothing more than the sum total of distances and durations between all the objects and events of the world. If we removed the contents of the universe, we would remove space and time also. This is the “relational” view of space and time: they are only the spatial and temporal relations between objects and events. The relational view of space and time was a key inspiration for Einstein when he developed general relativity.

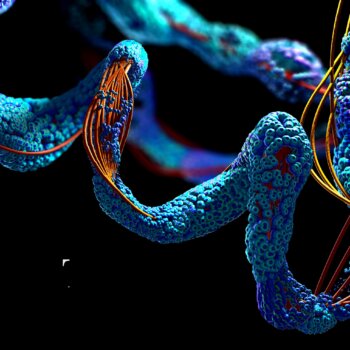

Rovelli makes use of this idea to understand quantum mechanics. He claims the objects of quantum theory, such as a photon, electron, or other fundamental particle, are nothing more than the properties they exhibit when interacting with – in relation to – other objects.

These properties of a quantum object are determined through experiment, and include things like the object’s position, momentum, and energy. Together they make up an object’s state.

According to Rovelli’s relational interpretation, these properties are all there is to the object: there is no underlying individual substance that “has” the properties.

So how does this help us understand quantum theory?

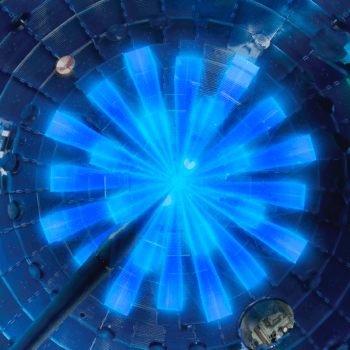

Consider the well-known quantum puzzle of Schrödinger’s cat. We put a cat in a box with some lethal agent (like a vial of poison gas) triggered by a quantum process (like the decay of a radioactive atom), and we close the lid.

The quantum process is a chance event. There is no way to predict it, but we can describe it in a way that tells us the different chances of the atom decaying or not in some period of time. Because the decay will trigger the opening of the vial of poison gas and hence the death of the cat, the cat’s life or death is also a purely chance event.

According to orthodox quantum theory, the cat is neither dead nor alive until we open the box and observe the system. A puzzle remains concerning what it would be like for the cat, exactly, to be neither dead nor alive.

But according to the relational interpretation, the state of any system is always in relation to some other system. So the quantum process in the box might have an indefinite outcome in relation to us, but have a definite outcome for the cat.

So it is perfectly reasonable for the cat to be neither dead nor alive for us, and at the same time to be definitely dead or alive itself. One fact of the matter is real for us, and one fact of the matter is real for the cat. When we open the box, the state of the cat becomes definite for us, but the cat was never in an indefinite state for itself.

In the relational interpretation there is no global, “God’s eye” view of reality.

What does this tell us about reality?

Rovelli argues that, since our world is ultimately quantum, we should heed these lessons. In particular, objects such as your favourite book may only have their properties in relation to other objects, including you.

Thankfully, that also includes all other objects, such as your coffee table. So when you do go to work, your favourite book continues to appear is it does when you were holding it. Even so, this is a dramatic rethinking of the nature of reality.

On this view, the world is an intricate web of interrelations, such that objects no longer have their own individual existence independent from other objects – like an endless game of quantum mirrors. Moreover, there may well be no independent “metaphysical” substance constituting our reality that underlies this web.

As Rovelli puts it:

We are nothing but images of images. Reality, including ourselves, is nothing but a thin and fragile veil, beyond which … there is nothing.

About the Author

This article was written by Peter Evans, ARC Discovery Early Career Research Fellow, The University of Queensland.