Why would you predict the world of tomorrow? What will technology bring next? And how will it impact people?

These were some of the questions that were asked at a Government backed workshop I attended aiming to provide a framework in which to answer the questions with predictions, shaping the strategy to build an Australia of the future.

Before the workshop, I had always doubted the usefulness or purpose of predicting technology, believing it was the domain of only so-called ‘futurists’. In fact, we’ve been attempting to do it since at least the 1800’s when the term, futurists, started to appear. Since then there has been a wealth of literature on the subject.

Foretelling the future was the once the realm of sorcerers, witches, artists and writers but it’s now become a very important part of business with some of the worlds largest consulting groups, companies and ‘Twitterarti’ instilling their own forms of ‘future predictions’ and its impact on their businesses.

Technology prediction for beginners

Let me start by acknowledging I’m not an expert or self-proclaimed futurist, more of a interested bystander with a natural inclination to ponder about the future and what might be.

Simply, these are some of the important questions to consider before you embark on your own future scenario considerations, and take real-life action!

Be as broad as possible

What exactly are you predicting? And how far into the future are you looking? Remembering that sweeping statements are rarely helpful to anyone;

“The pace of change is increasing”

Is a classic example of not really saying much about anything. In fact it’s exactly what you want to avoid when trying to come up with assumptions of the future. Is there evidence that the pace of change is faster now than before? Or is the real change in the fact we can access more information now? Technology means information is diffused more widely with services like YouTube reaching millions. Compare that with:

“The advent of pocket computers will change how we pay for things very quickly”

The important thing is to separate technological progress prediction (i.e. Moores law) and human behaviour (i.e. utility and impact of this change).

As a side note, people have been complaining about the pace of life for centuries.

Are you bored?

Then there’s the why. Are you just bored? Do you want to stir the pot and make some crazed claim about The Singularity happening next year? Or do you have to identify new opportunities in new markets for new products?

Risk only exists in the future and these days anyone who has to try and identify what risks exist are in many ways a futurist. Its just some decisions people make off the back of predictions impact the world in different ways:

‘Should I invest $10 million into this new Bitcoin startup to change payments or should I tell journalists I know everything about the future of Bitcoin?’

Future Fallacies

Once you’re in your future predicting mode (coffee helps) these three points ring true every time and are guidelines as to what to avoid, as articulated by Joseph J Corn:

- The fallacy of total revolution: new technologies will utterly change everything. This is a very important point to consider. While technology can have a profound impact on us, it’s highly unlikely to completely change our daily behaviour and life straight away. Indeed, you could argue the advent of mobile phones has done just this but in many respects it has just enhanced our existing ways of doing business and pleasure.

- The fallacy of social continuity: the technology will change, but society will continue as before.

- The fallacy of the technological fix: technology is designed to solve a problem and it will be solved, and in doing so it will not introduce any new problems.

Great predictions

Perhaps one of the most potent examples of a ‘great prediction’ is that of ‘smarter’ phones and what this would mean for technology industry.

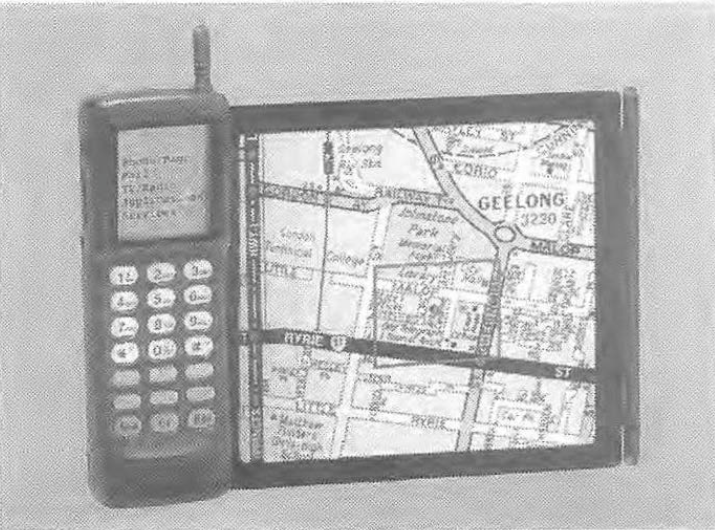

In 1994, Australian researchers predicted the convergence of technology industry and mobile computing.

“The personal communicator is a whole lot of things, all boiled into one. It’s called a Hypertel…it’s a mobile phone, but, of course, it includes a radio and television, a GPS with a map locater and a pretty fancy computer and a few other communication bits and pieces. The whole thing only weighs 150 grams. This model also has voice recognition and noise cancellation built in. Mind you, this one is not the “Rolls Royce” model. It’s a bit up-market from the base model, but not terribly so.

They even predicted a complementing medium, describing a sort of Google glass or augmented reality device;

If want a better display I can clip a small device onto the top of my glasses. It is like a pair of little television screens but they image directly onto the retina. There are earpieces that go with them for the sound…are high definition…It’s pretty well as good as being in a theatre.”

Then went to correctly predict that this device would act as a platform, providing a range of services, but incorrectly predicted how it would provided (bundled service versus software apps):

An enormous range of services are available now…I’ve paid for the full radio and TV service and the full mail service. Phone, remote banking and remote shopping are included in the base charge. I have a library subscription, as well. that lets me access any book, picture or video material that is avail able within the Australian library and museum system.

Hypertel, it’s a mobile phone, but, of course, it includes a radio and television, a GPS with a map locater and a pretty fancy computer…the whole thing only weighs 150 gram. This model also has voice recognition and noise cancellation built in. — R.H Frater & I.R. Elsum, 1994

Off the base of this scenario they predicted:

- Convergence: By the year 2020 information technology, telecommunications and entertainment systems will have merged.

- Power: “The availability of chips with power 10-100x greater than a top-of-the-line micro processor of 1994 at a cost of a few cents, will mean that such chips will be incorporated into many products.”

- Broadband: “By the year 2020 high-bandwidth communications will have become pervasive.”

- Business: “It was once thought that these large plants would put small companies out of business. In fact, an electronic system design team can do a complete custom design for a new product, using the manufacturer’s design rules, just as the designer of a microchip would have done in the nineties…they can even suggest changes to optimise manufacturing, and provide cost and delivery information for various production volumes.”

It was a pretty incredible set of predictions that today ring true in many ways.

Moving forward a few more years, I believe founders tend to make some of the best ‘futurists’ out there. They usually have a vision of a world that has not yet eventuated grounded on building real value in the present.

Fred Smith, the founder of FedEx — the leading global delivery business — had this to say about the delivery of groceries as part of a 1999 InternetWeek interview:

“A lot of retailers are coming to the conclusion that…maybe what we do is use the Internet in concert with our bricks and mortars. And that’s what I think will happen, because you have a lot of things that have very low value, and they don’t lend themselves to e-commerce and fast-cycle distribution. Groceries are the best example of that.”

FedEx was the pioneer of centralised, global courier services with cars, jets and distribution centres and even back in 1999, he recognised the partnership with brick-and-mortar grocery stores was the future.

Not so great predictions

History is also littered with terrible predictions that seem absurd today. In hindsight, everything would of been done differently so it’s much better to look at the behaviour and compensate for that.

“Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?” — Harry Warner,

Warner Brothers 1927

People usually underestimate the potential for change and I posit that this is truer when you start involving industry experts. As Howard Marks notes, general projections into the near future tend to “cluster around historic norms and call for only small changes.” The point is, people usually expect the future to be like the past and underestimate change.

However, an interesting nuance of ‘underestimating change’ is that it goes both-ways; predictions usually don’t account for how much better things can get, or how much worse;

“In August 1996, I wrote a memo showing that in the Wall Street Journal’s semi-annual poll of economists, on average the predictions are an extrapolation of the current condition. I invariably found that I had underestimated the extent of both the positive surprises and the shortfalls.”

Best and worse can translate into many different things in different contexts. Be careful who you listen to when validating your strategy for the future.

What to do with predictions

In 1610, the astronomer Johannes Kepler predicted there would be astronauts and wrote, in a letter to Galileo:

“Let us create vessels and sails adjusted to the heavenly ether, and there will be plenty of people unafraid of the empty wastes. In the meantime, we shall prepare, for the brave sky-travellers, maps of the celestial bodies.” — Johannes Kepler, 1610

In this one prediction Kepler justified to Galileo their motivations for mapping the skies. Even though it would be centuries after their work (and even a spacecraft named after him), he correctly predicted that human behaviour would advance both technology and skill to be able to explore the skies and space.

Ultimately, Kepler’s vision inspired life-long work that would provide one of the foundations for Isaac Newton’s theory of universal gravitation.

I believe, predictions of the future should inspire strategy, leveraging off vision.

What not to do

Technological predicting has been happening for a while and the benefits can be very interesting if informed predictions are taken seriously and meaningful action taken.

Predictions should influence strategy and one of the best examples is to take a look back to 1994.

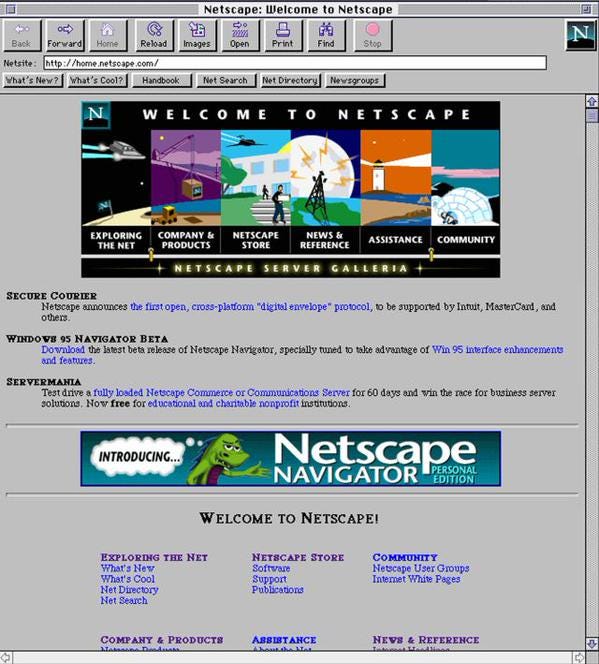

In Silicon Valley, KPCB, a renowned VC firm based in Silicon Valley, paid $5 million for around 25% of Netscape — one of the worlds first web browsers developed my Marc Andreessen.

In Australia, the researchers that predicted the iPhone in the same publication warned Australia needs to recognise;

“it is necessary for us to become a sophisticated manufacturing society as well as a sophisticated provider of services; support the needs of our fast-growing companies in high technology and value-added manufacturing and services; see the importance of education in systems engineering and of developing breadth and systems skills early in people’s careers”

Otherwise we’ll be left behind in a world dominated by technology, where companies will be able to play on a “global stage”.

Fast forward and KPCB hugely profited from Netscape’s IPO, which set off the first dot com boom, and subsequent $4 billion acquisition. Netscape influenced the development of the world wide web in profound ways and its founder now runs one of the most influential VC firms, Andreessen Horowitz, which invests in the next generation of technology entrepreneurs from around the globe.

Meanwhile, in Australia we’re seeing stagnation in Computer Science enrolments, declining resources sector and a sharemarket struggling to perform as predicted from the 2008 financial crisis. Meanwhile the very companies that KPCB funded years ago have become more valuable than our most recognised household names — Facebook is now worth more than BHP, Commonwealth Bank (one of Australia’s leading banks) and Woolworths (one of Australia’s leading grocery companies) combined.

Complacency is a killer and I think the Australian catch-cry “She’ll be right mate” is the perfect embodiment of how not to treat informed predictions.

Ultimately, I believe predictions of the future should not be ignored but motivate individuals to work towards a world they want to see, it should inspire strategy and leverage off their vision.

The world of tomorrow is built by us today.

About the Author

This article was written by James Alexander, Co-founder at Galileo Ventures to invest in under 30s & INCUBATE, Australia’s largest university startup accelerator.