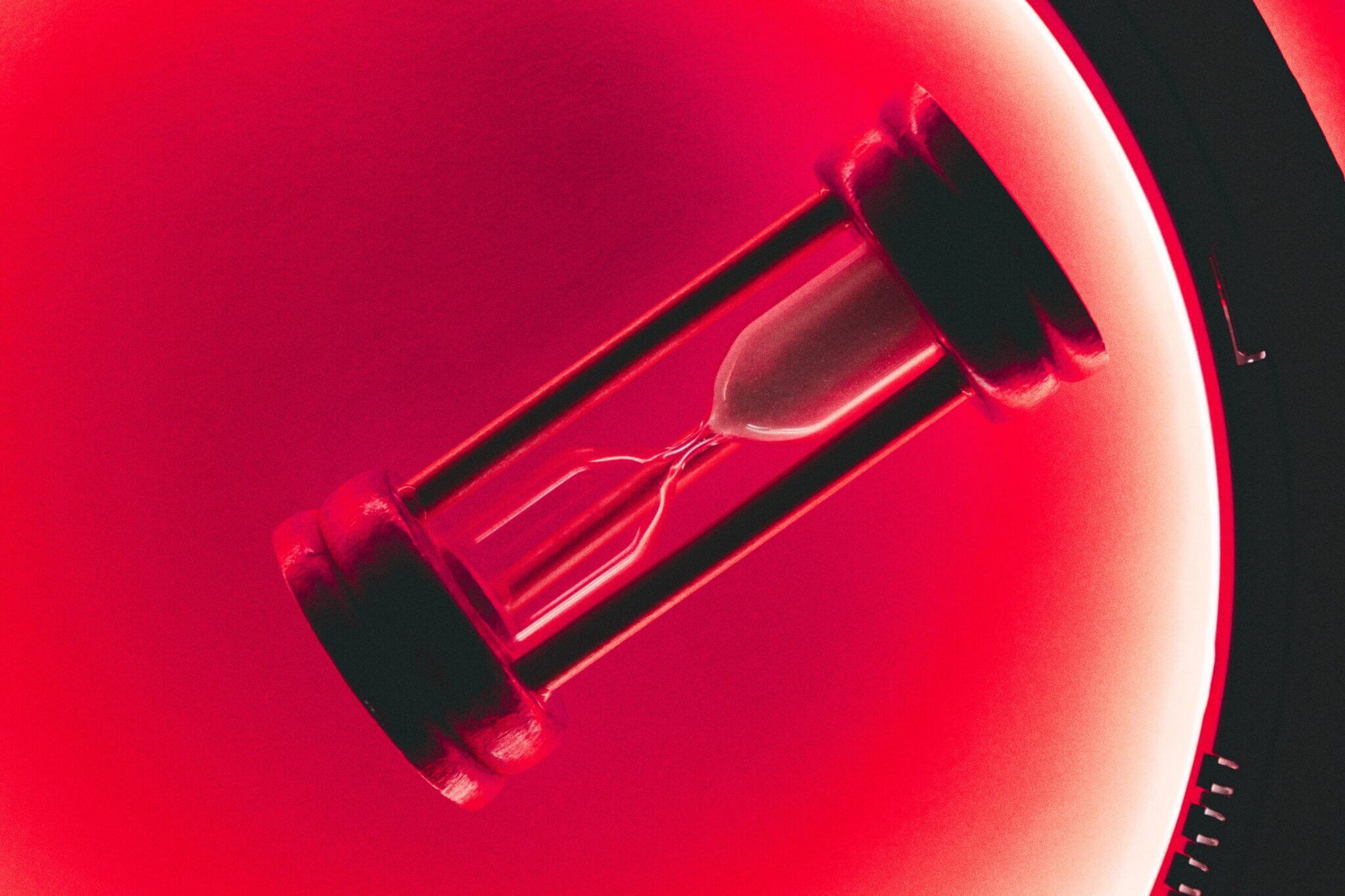

Aconsumer shopping for a midcentury sofa may be more likely to buy it if the background in its advertisement is a little disorganized. Likewise, people looking to purchase a new smartphone could more quickly pull the trigger if the ad were simple and sleek.

That’s because ads for vintage products are more appealing when they present messy images, according to new Texas McCombs marketing research, while those for futuristic items benefit from simplicity.

“The images we see in front of us have the power to transport us to the past or the future or even keep us in the present,” says Raj Raghunathan, Texas McCombs professor of marketing.

“And if we know images are going to transport us to past or future, we can take advantage of that when it comes to advertising and selling products.” —Raj Raghunathan

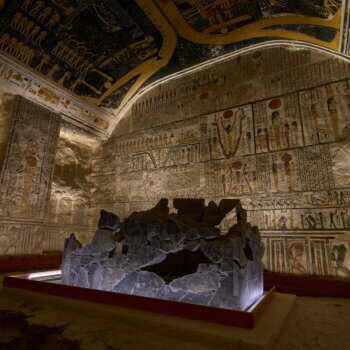

Consumers see products linked to the past, such as vintage products, more favorably when they’re accompanied by “high-entropy,” or disorganized, images. But with futuristic products, buyers tend to react better when the goods are paired with “low-entropy,” or less chaotic, images.

This occurs because disorganized images shift people’s focus to the past, while organized ones focus them on the future, says Raghunathan. When people see an image of a cracked egg, for example, they wonder, “What happened here? How did the egg get broken?” An image of an unbroken egg in a simple bowl, however, generates questions about what will happen next.

Along with Marketing Department Assistant Professor Adrian Ward and Gunes Biliciler of Koç Üniversitesi in Istanbul, Turkey, Raghunathan set out to investigate how the level of disorder in images affects consumers’ judgments and decisions. The study is the first of its kind to look at the connection between the phenomenon in physics known as entropy in a visual context and consumer behavior.

Understanding Orderly and Disorderly Images

Raghunathan and his colleagues ran several experiments. In the first, the researchers recruited 264 Amazon Mechanical Turk workers and asked them to write their thoughts about one of these images: a conference table scattered with papers, a table with organized papers, an intact hammer, and a broken hammer. Each image was selected at random.

The participants then stated whether images evoked thoughts of the past, present, or future. Participants who saw the disorganized table or broken hammer used more past-focused language than those who saw the clean table or intact hammer.

“Disorganized images tend to transport us to the past because they make us wonder what might have transpired here, or, why is there such a mess here?” Raghunathan says.

The researchers then ruled out an alternative explanation — that some images were just more attractive than others. They also found that people liked an ad for a traditional brand more when it was paired with an image of a splattered egg and an ad for a modern brand more when paired with the intact egg.

In their final experiment, 314 Amazon Mechanical Turk workers were asked to help determine the grade for a song created by music school students. Participants could pick between two song versions — which they were told had been inspired by either the past or future. Participants were then presented with two album covers — one was disorganized, a tangled string — and the other orderly, an untangled string — and they were asked to choose which image best went with the song.

Results showed participants who listened to the past-inspired song (even though both songs were really the same) picked the tangled string album cover, while those who listened to the future-inspired song selected the orderly string album cover.

Tailoring Images in Ads

The research has implications for marketers as they create ad campaigns.

“Depending on your product — whether it’s vintage or futuristic — you can play around with the entropy surrounding the image” — Raj Raghunathan

Marketers should also note that the study’s findings might be muted or invalid in certain contexts, such as in nature. For example, a neat pile of leaves may inspire thoughts about the past and who gathered the leaves rather than ideas about the future.

Including a human in images could also muddle the effects, Raghunathan says. A disorganized closet could make people think of the past. However, introduce a person into the image, and the focus could shift to the future amid speculation the person might tidy up. It’s an area for future research, he says.

“We are sense makers,” says Raghunathan. “People want to make sense of things and inquire as to why things are the way they are.”

“Consumers as Naive Physicists: How Visual Entropy Cues Shift Temporal Focus and Influence Product Evaluations” is forthcoming, online in advance in the Journal of Consumer Research.

Story by Deborah Lynn Blumberg