There’s never been a better time for a debate about influencer marketing: Google says searches for the term “influencer” are through the roof; there are supposed influencers with millions of followers unable to sell 36 t-shirts , while others sell even their bath water. All this would suggest to brands that advertising as they knew is dead, and that from now they need to spend their time trawling through Instagram or hiring any number of shady agencies until they find somebody willing to sell their name for them.

There is talk of 83% growth in a so-called industry built on false metrics, trivial and absurd premises, and distorted mechanisms. The social networks are filled with imaginary people whose followers, likes and comments are paid for and who have absolutely zero influence; while we are being exhorted to fight fake activity and introduce algorithms to detect it; at the same time as the need to tie influencers to contracts to ensure they comply with the number and frequency of mentions stipulated in them. Then there are the cases of influencers with unsavory associations or who are just idiots getting brands intro trouble, metrics that don’t add up, saturated social networks and fatigued users… In short, yet another supposed “industry” related to advertising whose death has long been foretold.

The first issue here is that this is not what influence is about. Notching up a certain number of followers, comments and likes on a social network is not influence; it just means that a certain number of people are prepared to follow your activities, for whatever reason. It doesn’t mean that they trust you, that they think your criteria are reliable or that they are willing to do what they are told, unless they are complete idiots — and of course there are people out there who fit that description. The moment somebody thinks that the people who follow them on a social network will do buy what buy what they are told unquestioningly, they have a problem. Actually, they have a whole bunch of problems, but above all a fundamental one: they don’t understand the game they are in.

Influence is not some urbi et orbi concept. It is limited to some areas and is achieved thanks to a series of mechanisms. It’s true that there are people who seem to exercise absolute influence and who are capable of turning everything they touch into gold, but that’s based on trust, albeit defined very loosely. Oprah was trusted when she recommended a book because she was supposed to have read it and because people were interested in what she read, as well as the fact that people identified with the authors she was promoting. Some people buy clothes because they identify with a certain style and want to look like the person they’re following. But let’s think for a moment: would Oprah’s book recommendations have worked if she always recommended the same publisher?

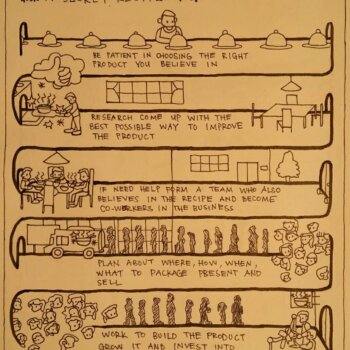

Influence works when it is credible. When it is corrupted, when there is no transparency, when it is based on lies or when we’re clearly being taken for fools, influence doesn’t work. When it becomes a contract in which somebody is told to make a certain number of mentions on certain channels in exchange for a certain amount of money, they stop being an influencer, and become something else: a mercenary. Influencers recommend what they know, what they like, what they know is good, based on a supposedly superior level of experience to you and me. If you do not have that experience and you simply sell what you have been told to sell, you are not an influencer, no matter how glamorous it sounds: you are simply a walking advertisement.

PROMOTED

As long as we continue trying to build an industry based on such absurd premises, we will continue to throw half (or more) away of what we spend on advertising, without knowing which half. It’s like betting when the dice are loaded, the cards marked, and the most savvy takes the pot. As things stand now, influence marketing is bunkum, and if your brand gets involved it will end up losing more than it wins. For all the amazing success stories, it simply isn’t possible to build an industry based on false premises. It doesn’t matter if you’re famous, an influencer or a microinfluencer, your sway is based on trust and the moment you start lying, your influence is over.

In short, the only thing that really works is sustainability, genuine relationships and transparency. If, as a brand, you have to stipulate how often an influencer has to mention your brand and where and when, while you cross your fingers in the hope he or she doesn’t do something disastrous, you’re playing a losing game. You’re not some modern marketing influencer, but pathetically lost, and sooner or later it will show. You are just a human billboard.

Back in the days of traditional advertising, everything was clear: nobody believed that the movie star sat around drinking coffee made from capsules all day or even that he had the slightest idea about coffee or that his desirability was due to a certain fragrance or that he always drove that particular car. He had just been paid to be associated with the product, and that was it. We all knew where we were. But with influencer marketing, the idea is to deceive, to make believe that a recommendation is genuine and to hide the fact that there is a contract, or worse still, fake it till you make it to try to gain the prestige required for brands to pay you to hawk their stuff.

The New York Times can say what it likes: influencers are not going to rule the world. At least not the kind of influencers we’ve seen so far. There will be people, creators rather than influencers, who will attain positions where they can help change things or sell products and services, but it won’t be thanks to a trashy industry based on poorly planned activity, and instead it will be based on a different set of premises. Influence is not what the supposed experts in influencer marketing want us to believe it is. It’s something else.

About the Author

This article was written by Enrique Dans, professor of Innovation at IE Business School and blogger at enriquedans.com.