The Romance of the Rose was by far the most popular work of medieval French literature: the text survives in over 300 copies and fragments. Featuring 101 images, an early 15th-century manuscript of the Romance of the Rose in the Getty Museum’s collection is one of the most lavishly illuminated copies in existence.

In the romance, a young man, known as the “lover,” finds himself on a quest for a beautiful rose, a symbol for his beloved lady. In the course of his arduous journey, he encounters characters such as the God of Love and Venus, who offer him advice about how to obtain the young woman or, alternatively, warn him against pursuing carnal love. As an art historian who studies the great cycles of miniatures that accompany this allegorical text, I’ve long been interested in how the imaginatively rendered images helped shape its reception.

Tips from an Unscrupulous “Friend”

The copy of the Romance of the Rose at the Getty contains a large number of unusual images illustrating the lover’s conversation with an allegorical figure simply called “Friend,” a character who offers lessons in the art of seduction. Some of the scandalous and even racy recommendations depicted in this manuscript might seem surprising to any of us who have a romanticized view of the Middle Ages as an era of courtly restraint and extreme piety:

Gifts and Fake Tears. In one image, Friend presents the lover with a purse and a chaplet, a delicate crown made of flowers. He explains that these two gifts could help gain a woman’s good graces: they served as tokens of love, but were not so expensive that they would render a man bankrupt. When a young man offers these gifts, Friend explains, he should pledge himself to the lady and feign intense emotion when expressing his devotion. He even recommends crying in order to convince her of his strong feelings. He explains, “And if you cannot weep, without delay take your saliva, or squeeze the juice of onions, or garlic…” in order to produce tears.

The Personification of Friendship Giving a Garland and Sacks of Gold for Alms to the Lover in Romance of the Rose, about 1405, unknown illuminator, made in Paris. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 14 7/16 x 10 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 7, fol. 48r

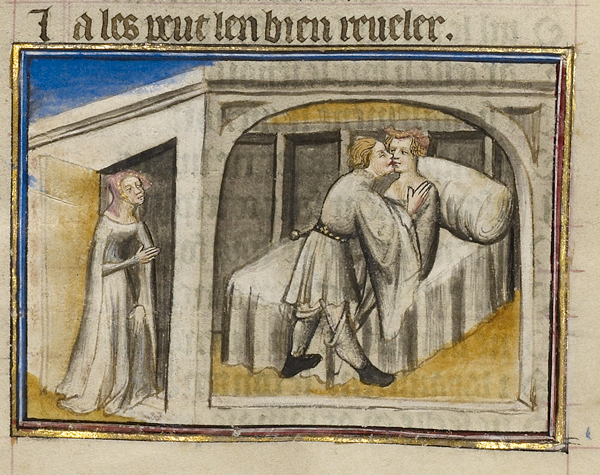

Secret Conquests. Another shocking image appears when Friend warns the lover against bragging about his love life. Friend advises that he keep all of his meetings with his beloved secret, because “boasting is a very base vice” and such slander could ruin a woman’s reputation. The artist represents an immodest bedroom scene: a man with stockings hanging indecorously at his knees kisses and caresses a woman wearing a stylish headdress. Just like the onlooker depicted in the image, we peer through a doorway and become witnesses to the intimate episode.

A Lover Entering the Bedroom of His Beloved in Romance of the Rose, about 1405, unknown illuminator, made in Paris. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 14 7/16 x 10 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 7, fol. 62v

Phony Tenderness. Friend also explains that, if a lady is sick, her lover must tend to her and convince her that he is devoted to nursing her back to health. He explains, “He should stay near her, watching, kiss her with tears in his eyes, and, if he is wise, vow many distant pilgrimages.” Friend even recommends proclaiming that he suffers when he sees her in pain. In the image, the artist represents a man tenderly placing one hand on the forehead of a sick woman, and, with the other, gently holding her wrist.

A Lover Finding the Pulse of His Beloved in Romance of the Rose, about 1405, unknown illuminator, made in Paris. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 14 7/16 x 10 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 7, fol. 62v

What Did Medieval Readers Think?

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, when this manuscript was illuminated, there was a heated debate in court circles regarding the morality of the text. Some thinkers, such as the famed author Christine de Pizan, claimed that the romance was misogynistic and encouraged immoral acts, namely copulation outside of marriage. Others claimed that characters such as Friend were intended to serve as negative examples, and that the romance could help women guard themselves against deceptive suitors. There is still no consensus among scholars regarding the meanings of this text and its accompanying images.

Warning lesson or incitement to sin—what do you think? Formulate your own opinion by exploring other images from this manuscript and browsing facsimiles of more than 130 other Rose manuscripts at the Roman de la Rose Digital Library. You can see the manuscript in person at the Getty Center in the exhibition I recently curated, Chivalry in the Middle Ages, where it appears alongside other objects that provide a broader view of medieval conceptions of courtly love.

_______

About the Author

This article was written by Melanie Sympson, a manuscripts scholar and curator of the exhibition Chivalry in the Middle Ages at the Getty Museum.

Quotations in this post are drawn from Charles Dahlberg’s translation of The Romance of the Rose(Princeton University Press, 1994).