We all know what emotions feel like, but what exactly are they? What is going on in our brain when we feel them, and why have we evolved to have them? These are all questions that science can’t yet answer, although researchers in many different areas, from neuroscience to AI, are trying to get to grips with them.

No one knows for sure why we feel emotions the way we do, but Darwin argued they evolved as a pre-verbal way of communicating. Facial expressions can demonstrate you are in need of help, sorry for something you have done, or even warn others to stay away if you are angry. However some people think there is a simpler explanation- the expressions evolved for one reason, and were then secondarily useful to tell what other people were feeling. For example, the widened eyes of fear could just be to help us to see better, and the disgust expression a way rejecting poisonous food. It is unlikely we will ever know for sure which of these theories is true, or whether there is another explanation entirely, but what is clear is that emotions are an important part of being human.

Learn more about Why do we have emotions?.2

As well as not knowing how they evolved, scientists are still unsure how exactly emotions work in the brain & body. It seems very intuitive that when we see something that angers us, we feel the emotion of anger and this triggers bodily responses- clenched muscles, a reddening face and the desire to move. And yet one of the most prominent theories of emotion turns this on its head. The James- Lange theory, put forward in the late 1800s, suggests that the bodily symptoms come first, and it is our brain’s interpretation of these symptoms that gives us the emotion. While it may be little over-simplified, modern evidence supports some elements of the theory. If you ask people to nod their head while listening to a speech, they are more likely to agree with it than if they were asked to shake their head instead. And faking a smile really can make you find things funnier or more enjoyable. But bodily symptoms aren’t everything. For one, the same symptom can be indicative of more than one emotion or bodily state- you might tremble out of fear, anger or cold, for example. And people who are paralysed from the neck down, so can’t feel bodily symptoms, can still experience emotions (although they are often dulled).

More recently, the Schacter-Singer theory has built on these ideas, suggesting that we cognitively assess both the bodily symptoms and the environment we are in to decide which emotion we are experiencing. Experimental support for this theory comes from the fact that when injected with adrenaline, but not told what it was, participants misinterpreted the symptoms as being caused by emotion. Which emotion they attributed it to depended on how the other people in the room were acting. If warned about the side effects of the injection, however, the same result was not seen.

Bodily symptoms of emotions seem to be inextricably tied to the cognitive sensation of the emotion, but they may have another role as wel. The somatic marker hypothesis suggests that behaviour, particularly decision making, can be guided by emotional processes. When we make decisions, we assess the value of the choices available, using cognitive and emotional processes. We like to think we mainly rely on rational, cognitive factors, but this is far from true. When decisions are complex or conflicting, our cognitive processes can become overloaded. In these cases we rely more on emotions in the form of ‘somatic markers’.

Somatic markers can be sub-conscious, and are emotional responses that develop based on past experience and recur during the decision making process. For example, if offered a choice between two decks of cards, one of which provides a riskier gamble with big returns but bigger losses, over time most people begin to edge away from this pack, as their somatic markers kick in to give them a negative feeling towards it. They may not consciously realise they are doing this, or be able to say which deck is the ‘bad’ one if asked, however their emotional response to it directs their decision making. The argument is that this applies in real life decisions as well; sub-conscious emotional reactions to some of the options can bias our decisions without us even knowing it. How important these findings really are in our day-to-day lives is difficult to know for sure.

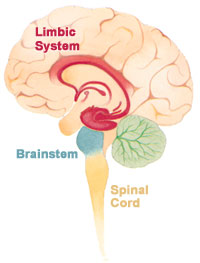

In trying to understand emotions, one route that scientists have taken is to examine where they reside in the brain. Historically, emotions have been thought to be based in the limbic system. However, improvements in imaging technology show this to be an over-simplification. While these regions are important, emotional networks also include areas such as the frontal cortex not included in the traditional limbic system, while there are regions in the limbic system which now seem to be more related to memory than emotion

Specific emotions

Lying is part of life- whether it is telling your aunt how much you love the hideous jumper she got you for your birthday or calling in sick at work. But some people claim to be able to spot lies, or more specifically, faked emotion, using micro-expressions. Micro-expressions are facial expressions that last between 1/15th and 1/25th of a second but can be seen by filming a person and slowing down the footage, or by trained viewer. They often give away an emotion the person is trying to conceal.

This is an example of emotional leakage- elements of the emotion you are trying to hide (either from yourself or from others) can come through the ‘mask’ of the faked emotion. It is harder to fake negative than positive emotions, so these are the most likely ones to ‘leak’. It has been claimed that by learning to spot micro expressions you can tell if someone is lying, but research has shown they aren’t consistent enough to be a valid or useful method.

We have all felt that crawling feeling of disgust at a maggot or a pile of vomit. This feeling of repulsion helps protect us from disease by encouraging us to avoid potential sources of contamination or infection. However, we also feel disgust towards certain acts of behaviour which we deem unacceptable, suggesting disgust has a moral component as well. How these components interact isn’t clear, and there are many other fascinating open questions in the area of disgust research.

Blushing is a reflex that occurs in some humans when they feel embarrassed. The feeling of embarrassment causes the release of the hormone adrenaline, dilating the blood vessels in your face and increasing blood flow, causing heat and redness. Humans are the only animal known to blush, but it seems to be common amongst humans of every race. However it isn’t clear why we have evolved to blush.

It could just be a side-product of another bodily process which, while not providing any advantage, also didn’t disadvantage the blusher, so was not selected against. However, humans are a highly social species, and use many different forms of communication; it is likely that the earliest forms involved body language and facial expressions. It may be that blushing was an early way to signal an apology, showing that you regretted an action, and you respected the person you were communicating with. This may have avoided punishment-whether physical violence, or simply being shunned by the community, which would have had devastating effects on an early human’s survival chances.

There is evidence that even in the modern world, we think people who blush after committing a social faux-pas are more reliable and trustworthy, and we tend to like these people more than those who don’t show embarrassment. So next time your face starts turning red and you wish the ground would swallow you up, you can reassure yourself that what is happening will only re-enforce your social ties with those around you.

Scary movies, ghost stories and theme park rides are hugely popular- probably because of the release of hormones that accompanies the feeling of fear. However if you ask a fan what the most intense moment of the experience is they will probably tell you it is the few seconds before the monster appears, or just before the ride plunges from a great height. What you experience in these seconds is a feeling of suspense, which is an emotion that we don’t know very much about.

One theory suggests it is a moment of heightened awareness, making us more alert, and better primed to spot danger. Recently, a study measured the brain activity of people watching suspenseful films. The calcarine sulcus, one of the first areas of the brain to receive and process visual information, was found to be highly active, and the researchers found that the brain’s focus narrowed during the suspenseful scenes. Normally, when a film is presented with a flashing checked boarder, many neurons in the brain respond to this border, rather than the scene itself. When feeling suspense, however, attention shifted from the boarder to the centre of the scene. One suggestion is that this increases memory of the information focussed on, but further research is required before reliable conclusions are formed.

One of the easiest ways to induce specific emotions in someone is to play them music. Music is a mixture of pitch, tone and pattern- our brain combines information about these factors into a single entity that we enjoy, or (sometimes) dislike. Music can make us feel emotions in a way almost nothing else can- whether it is the heightened fear the soundtrack gives when watching a scary movie, or the ‘chills’ experienced when listening to a particularly haunting melody. While we know there are a wide range of brain areas involved in the emotions elicited by music, we don’t know why, or how, music can create such intense feelings in the listener.

One of the most dramatic emotional reactions to music is the goose bumps, shivers down the spine and increase in pulse that is known as ‘frisson’. These bodily symptoms normally signal fear as the fight or flight response is engaged and you prepare to run away, or attack. Goose bumps in this situation are thought to stem from when we had fur; causing it to stand on end would help retain heat, but also makes you look bigger to help scare off an attacker. But why music should trigger these effects is less clear.

We know that unexpected stimuli can cause the same effect and this may include sudden changes in music’s tempo or volume. You quickly realise there isn’t actually any danger present, so the feeling of fear never occurs, but you are left with the physical symptoms of frisson. Another clue to why this occurs may be the fact that opera singers perform at a similar range to a human scream- which is evolutionarily adapted to cause a fear response.

However some argue that triggering the fear response in the absence of danger isn’t enough to induce frisson- we also need to be feeling pleasure at the same time. Positive stimuli such as food, sex and music, cause the release of dopamine in the brain. It could be this mix of pleasure and fear that produces the emotion- which is why it feels similar to the first touch from a romantic partner or the thrill of riding on a roller coaster.

Machines with Emotions?

As the abilities of AI and computer learning increase, some people have turned their attention to the idea of programming robots with emotions. Whether this would be beneficial, or even possible is an area of debate, as are the moral implications if it should occur. However the first step, which is currently achievable, is to produce machines that appear to have emotions- this will make them much easier and more pleasant for humans to interact with.

Machines have already been created that can simulate facial expressions when given the input of a certain emotion. As these types of abilities improve, we may be able to create robots that appear to react just like we do, emotionally. But at what point would we argue that they are actually feeling the emotion, as opposed to just simulating it? If we see them reacting just like a human, who is to say the human has emotional experiences and the robot doesn’t? This is a question that philosophers have long wrestled with, and is unlikely to be resolved soon.

If we did accept that AI could become sentient and experience emotions, a whole new moral area of discussion opens up. Could it ever be acceptable to own a sentient machine, or should they be given independence? Would these super intelligent beings end up trying to enslave us? And could we stop them if they did? These are all questions that will need to be grappled with as the improvements in technology mean we are moving ever closer to the world of science fiction.

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Ginny Smith, Johanna Blee, Joshua Fleming, and Holly Godwin.